Etiology

The causes of aortic stenosis (AS) can be categorized into three main types: congenital abnormalities, degenerative changes, and inflammatory diseases. Isolated aortic stenosis is most commonly congenital or degenerative in origin, with inflammatory causes being rare. It occurs more frequently in males.

Pathology

Congenital Abnormalities

Unicuspid Valve Abnormality

This is a severe congenital cause of aortic stenosis and one of the major causes of infant mortality. Most patients develop symptoms during childhood and require corrective treatment before adolescence.

Bicuspid Valve Abnormality

Approximately 1-2% of the population is born with a bicuspid aortic valve, with a higher prevalence in males. While the bicuspid valve does not cause stenosis at birth, its abnormal structure leads to hemodynamic disturbances over time, resulting in valve leaflet damage, fibrosis, and calcification. This progressively reduces valve mobility and eventually causes stenosis. About 1/3 of bicuspid valves develop stenosis, another 1/3 develop regurgitation, and the remaining cases may only cause mild hemodynamic abnormalities. This process takes decades, with symptoms typically appearing after the age of 40. Congenital bicuspid valve abnormality is a common cause of isolated aortic stenosis in adults and is prone to complications such as infective endocarditis.

Quadricuspid Valve Abnormality

This rare congenital anomaly affects 0.008-0.033% of the population and occurs equally in males and females. The abnormal hemodynamics primarily cause aortic regurgitation, though a minority of cases may present with aortic stenosis.

Senile Aortic Valve Calcification

Age-related degenerative aortic stenosis has become the most common cause of aortic stenosis in adults. It is estimated that approximately 2% of individuals over the age of 65 and 4% of those over 85 have this condition. The degenerative process involves proliferative inflammation, lipid accumulation, activation of angiotensin-converting enzyme, infiltration of macrophages and T lymphocytes, and eventual calcification. Calcium deposits at the base of the valve leaflets restrict their mobility, leading to aortic valve stenosis.

Rheumatic Heart Disease

The primary inflammatory cause of aortic stenosis is rheumatic fever, though other connective tissue diseases are rare contributors. Rheumatic inflammation causes commissural fusion, leaflet fibrosis, calcification, rigidity, and contraction deformities, ultimately leading to aortic stenosis. Rheumatic aortic stenosis is often accompanied by aortic regurgitation and mitral valve disease.

Pathophysiology

In normal adults, the aortic valve area is 3-4 cm2. Hemodynamic changes are not significant until the valve area is reduced to 1/3 of its normal size. When the valve area decreases to ≤1.0 cm2, there is a marked systolic pressure gradient between the left ventricle and the aorta. This leads to concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall, with increased thickness of the free wall and interventricular septum. The compliance of the left ventricle decreases, and the relaxation rate slows, resulting in a progressive rise in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. This elevated pressure is transmitted through the mitral valve to the left atrium, increasing left atrial afterload. Chronic left atrial overload eventually raises pulmonary venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and pulmonary artery pressure, clinically manifesting as symptoms of left-sided heart failure.

Additionally, the increased left ventricular systolic pressure caused by aortic stenosis leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and prolonged ejection time, increasing myocardial oxygen demand. Aortic stenosis often reduces diastolic pressure in the aortic root and elevates left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, compressing subendocardial vessels and reducing coronary perfusion. These changes, combined with reduced cerebral blood flow, result in myocardial ischemia, hypoxia, and angina. They further impair left ventricular function and may cause symptoms of cerebral ischemia, such as dizziness, amaurosis fugax, and syncope.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Patients with aortic stenosis often remain asymptomatic for a long period. Symptoms typically appear only when the valve area decreases to ≤1.0 cm2. The classic triad of symptoms for AS includes dyspnea, angina, and syncope.

Exertional dyspnea is the most common initial symptom in late-stage AS, occurring in approximately 95% of symptomatic patients. As the disease progresses, patients may develop paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, or even acute pulmonary edema.

Angina is often the earliest and most common symptom in severe AS, affecting approximately 60% of symptomatic patients. It is typically triggered by physical exertion and relieved by rest or sublingual nitroglycerin, reflecting an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. The mechanisms of angina in AS include:

- Increased myocardial oxygen consumption due to left ventricular (LV) wall thickening, elevated systolic pressure, and prolonged ejection time

- Reduced capillary density relative to the hypertrophied myocardium

- Subendocardial coronary artery compression caused by elevated diastolic intraventricular pressure, leading to inadequate myocardial perfusion

- Reduced coronary perfusion pressure due to a decrease in the diastolic aortic-to-LV pressure gradient

Syncope occurs in 15-30% of symptomatic patients and may present as transient episodes of amaurosis fugax or be the initial symptom. It is often exertional, occurring during physical activity, though it can also occur at rest. The possible mechanisms include:

- During exertion, peripheral vasodilation occurs, but cardiac output fails to increase proportionally, exacerbating myocardial ischemia and reducing cardiac contractility, leading to further decreases in cardiac output.

- After exertion, reduced venous return decreases LV filling and cardiac output.

- At rest, syncope is often caused by arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular block, or ventricular fibrillation), resulting in a sudden drop in cardiac output.

Signs

The cardiac borders are normal or slightly shifted to the left. A systolic lifting pulsation may be palpable at the apex. Systolic blood pressure is reduced, pulse pressure is narrowed, and the pulse is weak and delayed. In severe AS, simultaneous palpation of the apex and carotid artery reveals a noticeable delay in carotid pulsation.

The first heart sound is usually normal. In cases of severe stenosis or calcification, prolonged LV ejection time leads to a weakened or absent second heart sound (aortic component). Severe AS may also result in paradoxical splitting of the second heart sound due to delayed aortic valve closure. A prominent fourth heart sound may be heard due to forceful left atrial contraction. If the valve leaflets retain mobility, an ejection click may be heard at the right or left sternal border and apex. However, in cases of calcified and immobile leaflets, the ejection click disappears.

The typical murmur in AS is a harsh, loud ejection systolic murmur (grade ≥3/6) with a crescendo-decrescendo pattern, best heard at the right upper sternal border (1st-2nd intercostal space) and radiating to the neck. Generally, the louder and longer the murmur, and the later its peak intensity, the more severe the stenosis. In cases of LV failure or reduced cardiac output, the murmur may diminish or disappear. After long diastolic intervals, such as post-premature contraction compensatory pauses or during prolonged cardiac cycles in atrial fibrillation, the increased stroke volume enhances the murmur.

Laboratory and Other Examinations

Chest X-ray

The cardiac silhouette is usually normal or slightly enlarged, with mild outward bulging of the lower third of the left heart border. The left atrium may be slightly enlarged, and 75-85% of patients show ascending aortic dilation. Lateral X-rays may reveal aortic valve calcifications.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

In mild cases, the ECG is normal. Moderate stenosis may show increased QRS voltage with mild ST-T changes. Severe cases may present with signs of LV hypertrophy, strain, and left atrial enlargement.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the preferred method for evaluating AS.

Two-dimensional echocardiography shows thickened aortic valve leaflets with increased echogenicity (indicating calcification), reduced leaflet motion during systole (often <15 mm), and slowed opening. Symmetric hypertrophy of the LV posterior wall and interventricular septum, left atrial enlargement, and post-stenotic dilation of the aortic root may also be observed. Congenital abnormalities, such as unicuspid, bicuspid, or quadricuspid valves, can be identified.

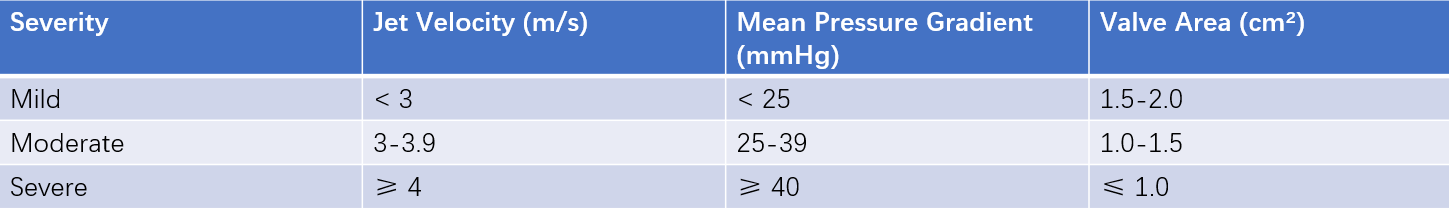

Table 1 Assessment of aortic stenosis severity

Color Doppler echocardiography demonstrates accelerated turbulent flow below the valve with a mosaic pattern. Continuous-wave Doppler can measure transvalvular flow velocity, calculate the peak pressure gradient (LV-to-aorta systolic pressure difference), and estimate valve area to assess stenosis severity.

Cardiac Gated Contrast-Enhanced CT

This provides important information for treatment planning. It can clearly visualize the structure of the aortic root, including congenital valve abnormalities and their types, aortic annulus size, the extent and distribution of valve calcification, leaflet thickening, and the location and height of coronary ostia. Enhanced CT can also identify ascending aortic dilation, its degree, and vascular access for interventional procedures (e.g., femoral artery diameter and tortuosity).

Cardiac Catheterization

Left heart catheterization and angiography can measure the pressure gradient between the LV and aorta, reflecting the severity of AS. Angiography can also determine the type of stenosis (subvalvular, valvular, or supravalvular). For older patients, coronary angiography should be performed before valve replacement surgery to identify coexisting coronary artery disease and guide surgical planning.

Diagnosis

The presence of a typical ejection systolic murmur in the aortic valve area makes the diagnosis of aortic stenosis relatively straightforward, and echocardiography is essential for confirmation. AS with concomitant regurgitation and mitral valve disease is often indicative of rheumatic heart valve disease. In patients under 65 years old with isolated aortic valve disease, congenital abnormalities are the most common cause, whereas degenerative calcific changes are more prevalent in those over 65 years old.

Differential Diagnosis

Clinically, AS should be differentiated from other conditions that produce systolic murmurs in the aortic valve area. Echocardiography is helpful in distinguishing these conditions.

Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

In HOCM, systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve leads to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. A mid-to-late systolic ejection murmur can be heard at the left sternal border (4th intercostal space) but does not radiate to the neck or subclavian area. A rapidly rising, bisferiens pulse is characteristic. Echocardiography shows asymmetrical left ventricular wall hypertrophy, with a significantly thickened interventricular septum (septal-to-posterior wall thickness ratio ≥ 1.3).

Other Conditions

Congenital supravalvular or subvalvular aortic stenosis can also produce systolic murmurs. If the murmur radiates to the lower left sternal border or apex, it should be differentiated from the holosystolic murmurs of mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, or ventricular septal defect.

Complications

Atrial fibrillation occurs in approximately 10% of patients, leading to increased left atrial pressure and significantly reduced cardiac output. This can result in rapid clinical deterioration with severe hypotension, syncope, or pulmonary edema. Aortic valve calcification involving the conduction system may cause atrioventricular block. Left ventricular hypertrophy, subendocardial ischemia, or coronary embolism can lead to ventricular arrhythmias.

Sudden cardiac death is rare in asymptomatic patients, with an annual incidence of approximately 1%. However, the risk is significantly higher in symptomatic patients, with an annual incidence of 8-34%.

The natural course of congestive heart failure (CHF) is significantly shortened once left heart failure develops. Without surgical intervention, 50% of patients die within 2 years after CHF onset.

Although uncommon, infective endocarditis is more frequently seen in patients with congenital bicuspid aortic valve abnormalities.

Systemic embolism is rare, but more commonly observed in patients with calcific aortic stenosis.

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage may occur in patients with arteriovenous malformations, a condition known as Heyde's syndrome. This is rare, with an incidence of 1.5-3%, and hemorrhage is typically occult and chronic. Hemorrhage often resolves after valve replacement surgery.

Treatment

General Management

Patients should avoid excessive physical exertion and strenuous activity. Regular follow-up is crucial for determining the timing of interventional or surgical treatment. Patients should be educated to seek medical attention immediately if symptoms develop. For patients with suspected symptoms, stress echocardiography can help clarify the diagnosis.

Severe AS without Symptoms

Reassessment is recommended at least every 6 months.

Moderate AS

Reassessment every 1-2 years is advised. For patients with significant valve calcification, follow-up intervals should be shortened to at least yearly.

Mild AS

Annual evaluation is recommended if significant calcification is present; otherwise, follow-up can be extended to every 2-3 years.

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy has limited efficacy, and no specific drugs are available for AS. Treatment focuses on symptomatic and supportive care. Infective endocarditis prevention is particularly important in at-risk populations. Rheumatic fever prevention is crucial for patients with rheumatic heart disease. Blood pressure control is essential. Sodium restriction, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors can be used. Arrhythmias that destabilize hemodynamics should be treated aggressively. For atrial fibrillation, beta-blockers or digoxin can be cautiously used to control ventricular rate, but acute left heart failure should be monitored carefully. Vasodilators such as nitrates and nifedipine, which reduce systemic blood pressure and coronary perfusion pressure, should be avoided. There is no clear evidence that statins slow the progression of AS.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention should be considered for all symptomatic patients.

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR)

SAVR is the primary treatment for adult AS. Indications include severe stenosis with symptoms such as angina, syncope, and heart failure. Asymptomatic patients should also be considered for surgery if they meet any of the following criteria:

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%

- Reduced exercise tolerance or decreased systemic blood pressure during exercise

- Extremely severe AS (jet velocity > 5 m/s or mean pressure gradient > 60 mmHg)

- Rapid progression of AS (annual increase in jet velocity > 0.3 m/s)

The surgical mortality rate is ≤5%, and long-term outcomes are better than those for mitral valve disease or aortic regurgitation.

Aortic Valve Commissurotomy under Direct Vision

This is suitable for children and adolescents with severe, non-calcified congenital AS, even if asymptomatic.

Interventional Therapy

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR)

Since the first TAVR procedure in 2002, it has become a primary treatment for severe AS. For patients over 65 years old with severe AS, TAVR is a viable option if the indication for valve replacement is clear and the anatomical structure is suitable.

Percutaneous Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty (PBAV)

Unlike percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty, PBAV has limited clinical application due to a high rate of restenosis and its inability to reduce mortality in severe AS. PBAV may be used as a bridging therapy to surgery or TAVR in patients with hemodynamic instability, high surgical risk, or those requiring urgent non-cardiac surgery.

Prognosis

The survival rate of asymptomatic patients is similar to that of the general population, with a 3-5% risk of sudden cardiac death. The appearance of the classic symptom triad indicates a poor prognosis:

- Angina: 50% of patients die within 5 years without surgery

- Syncope: 50% of patients die within 3 years without surgery

- Congestive heart failure: 50% of patients die within 2 years without surgery

Successful aortic valve replacement significantly improves prognosis, quality of life, and long-term survival compared to medical management.