Etiology

Mitral stenosis (MS) is primarily caused by rheumatic fever and is most common in young adults aged 20-40 years. Approximately 70% of patients are female. About 50% of patients have no history of acute rheumatic fever but often have a history of recurrent streptococcal infections leading to upper respiratory tract infections. It typically takes at least 2 years or longer after an episode of acute rheumatic fever for significant mitral stenosis to develop. Repeated episodes of acute rheumatic fever tend to result in mitral stenosis earlier compared to a single episode. Rare causes of mitral stenosis include congenital abnormalities and annular calcification.

Pathology

The pathological changes in rheumatic mitral stenosis include fibrous thickening and calcification of the valve leaflets and commissures, fusion and fibrosis at the commissures, and thickening, shortening, and fusion of the chordae tendineae. The stenotic mitral valve often takes on a funnel shape, with the orifice resembling a fish mouth. If chordal retraction and adhesion predominate, mitral regurgitation may also occur. Chronic mitral stenosis can lead to left atrial enlargement, elevation of the left main bronchus, calcification of the left atrial wall, left atrial mural thrombus formation, thickening of the pulmonary vascular walls, and right ventricular hypertrophy and dilation. Isolated mitral stenosis accounts for approximately 25% of cases of rheumatic heart disease, while mitral stenosis with mitral regurgitation accounts for about 40%. The aortic valve is often concurrently affected.

Pathophysiology

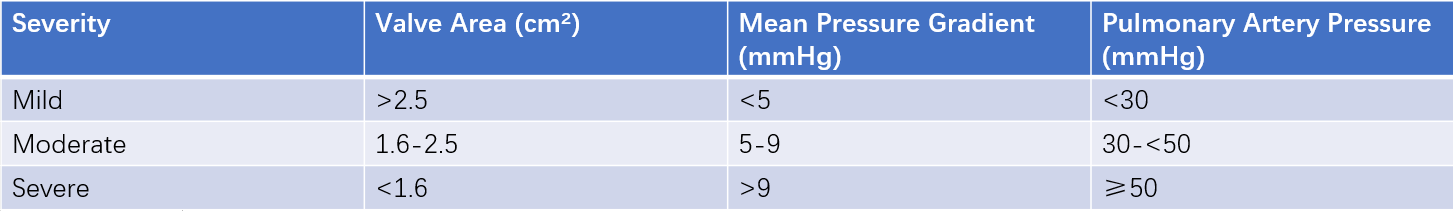

The normal mitral valve area (MVA) in adults is 4.0-6.0 cm2. Mild stenosis occurs when the MVA is reduced to more than 2.5 cm2, moderate stenosis when it is 1.6-2.5 cm2, and severe stenosis when it is less than 1.5 cm2. As mitral stenosis progresses, the transvalvular pressure gradient increases to maintain normal blood flow into the left ventricle and sustain cardiac output. The earliest hemodynamic change in mitral stenosis is an increase in left atrial pressure due to obstruction of diastolic blood flow into the left ventricle. This pressure elevation can be transmitted to the pulmonary veins, resulting in pulmonary congestion, which can lead to massive hemoptysis in severe cases. Initially, elevated left atrial pressure occurs only during conditions that increase heart rate, such as exercise, emotional stress, infection, pregnancy, and atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate. As stenosis worsens, left atrial pressure remains elevated even at rest, leading to symptoms such as exertional dyspnea and other manifestations of elevated pulmonary venous pressure. Chronic pulmonary venous hypertension can cause increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary artery pressure. If mitral stenosis is left untreated, irreversible changes in the pulmonary vasculature may develop. Severe pulmonary hypertension can result in right ventricular dilation and right heart failure. At this stage, symptoms of pulmonary congestion may improve, but systemic venous congestion symptoms and signs become more pronounced.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

The progression of mitral stenosis is gradual, with an initial slow development phase lasting 20-40 years during which clinical symptoms may be subtle or absent, followed by a rapid progression in the later stages.

Dyspnea is an early symptom, initially presenting as exertional dyspnea. In advanced stages, dyspnea may occur even at rest and can manifest as orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. Factors such as rapid ventricular rate in atrial fibrillation, infections, fever, pregnancy or labor, physical exertion, and rapid intravenous fluid administration can precipitate acute pulmonary edema.

Hemoptysis may occur in the following scenarios:

- Sudden massive hemoptysis due to rupture of dilated bronchial veins, which may be the first symptom of mitral stenosis, often seen in the early stages

- Blood-streaked sputum or bloody sputum during paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or coughing.

- Pink, frothy sputum during acute pulmonary edema

- Hemoptysis due to pulmonary infarction caused by embolization of systemic venous thrombi or right atrial thrombi, a rare complication in mitral stenosis with heart failure

Cough frequently occurs, often at night or after physical exertion. It may be caused by bronchial mucosal congestion and edema leading to bronchitis or by left atrial enlargement compressing the left main bronchus.

Severe left atrial enlargement and pulmonary artery dilation can compress the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing hoarseness, or compress the esophagus, leading to dysphagia. Right heart failure may result in symptoms of gastrointestinal congestion, such as reduced appetite, abdominal distension, and nausea.

Signs

Patients with severe mitral stenosis often exhibit characteristic mitral facies, with cyanotic, reddish cheeks.

Typical auscultatory findings in mitral stenosis include a low-pitched, rumbling diastolic murmur heard at the apex, which is localized and non-radiating. It is most prominent at the apex in the left lateral decubitus position, and a diastolic thrill may often be palpable. If the first heart sound (S1) is accentuated and an opening snap (OS) is heard, it suggests pliable and mobile valve leaflets.

Accentuation of the first heart sound is due to low leaflet positions during diastole and rapid closure during systole, producing a sharp, snapping quality.

The opening snap follows the second heart sound (S2) and is caused by the sudden tensing of the mitral valve during its opening. It is more pronounced during expiration and is a characteristic finding in mitral stenosis, indicating good valve elasticity.

If the valve leaflets are calcified and immobile, S1 may be diminished, and the OS may disappear.

When pulmonary hypertension develops, a right ventricular heave may be palpable at the left lower sternal border, and the pulmonary component of the second heart sound (P2) may be accentuated or split. Relative pulmonary regurgitation due to pulmonary artery dilation may produce a decrescendo early diastolic murmur (Graham-Steell murmur) at the left sternal border in the 2nd-4th intercostal spaces, which must be differentiated from an aortic regurgitation murmur. In cases of right ventricular enlargement with tricuspid regurgitation, a holosystolic blowing murmur may be heard at the left sternal border in the 4th-5th intercostal spaces, which intensifies during inspiration.

Laboratory and Auxiliary Examinations

X-ray Examination

In the posteroanterior view, findings may include straightening of the left heart border, a double contour of the right heart border indicating enlargement of both atria, left atrial enlargement, prominence of the pulmonary artery segment, a small aortic knuckle, and interstitial pulmonary edema (e.g., Kerley B lines).

In the left anterior oblique view, left atrial enlargement may elevate the left main bronchus, while in the right anterior oblique view, left atrial enlargement may compress the lower esophagus, causing it to shift posteriorly.

In severe cases, significant left atrial and right ventricular enlargement may result in a pear-shaped cardiac silhouette.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

In severe mitral stenosis, mitral P waves may appear, characterized by a P wave duration >0.12 seconds with a notched appearance. Additionally, there may be an increase in the terminal negative deflection of the P wave in lead V1 (Ptf-V1).

The QRS complex may show right axis deviation and signs of right ventricular hypertrophy.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is highly valuable for assessing the pathological changes of the mitral valve and the severity of stenosis.

M-mode Echocardiography

Findings include enhanced echogenicity of the mitral valve leaflets, reduced mobility, a hockey stick appearance of the anterior leaflet motion, a decreased EF slope, and synchronous motion of the anterior and posterior leaflets.

Two-dimensional Echocardiography

It displays a doming appearance of the mitral valve during diastole, thickening, adhesion, and fusion of the commissures and chordae tendineae, and a fish mouth appearance of the narrowed valve orifice. The anterior leaflet shows a hook shape during diastole, and the posterior leaflet has reduced mobility. Left atrial and right ventricular enlargement may be present, and thrombus formation in the left atrium can be visualized in severe cases of stenosis.

Color Doppler Imaging and Continuous Doppler Imaging

They reveal multi-colored turbulent diastolic flow jets and high-velocity forward turbulent flow spectra across the stenotic valve.

Echocardiography also provides information on atrial and ventricular size, wall thickness and motion, ventricular function, pulmonary artery pressure, other valvular abnormalities, and congenital anomalies. Continuous or pulsed Doppler imaging can accurately measure the diastolic trans-mitral pressure gradient and mitral valve area, with results correlating well with cardiac catheterization measurements. This allows for precise assessment of stenosis severity.

Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE)

It accurately evaluates mitral valve morphology, detects thrombi in the left atrial appendage or left atrial walls, and assesses changes in atrial and ventricular chamber morphology and function. TEE has a sensitivity and specificity of over 98% for thrombus detection.

Table 1 Echocardiographic assessment of mitral stenosis severity

Cardiac Catheterization

When interventional or surgical treatment is being considered, cardiac catheterization can be used to simultaneously measure pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and left ventricular pressure. This allows for the determination of the transvalvular pressure gradient and an accurate assessment of the severity of stenosis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mitral stenosis can be confirmed based on characteristic cardiac murmurs and echocardiographic findings. Echocardiography is also helpful in differentiating mitral stenosis from other conditions such as relative mitral stenosis, left atrial myxoma, tricuspid stenosis, and primary pulmonary hypertension.

Complications

Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

A common complication, AF may trigger the first episode of dyspnea and mark the onset of significant functional limitation. It often begins with atrial premature beats, progresses to paroxysmal atrial flutter or fibrillation, and eventually becomes chronic. AF can reduce cardiac output by 20%-25%, precipitating or worsening heart failure.

Acute Pulmonary Edema

It presents with sudden onset of severe dyspnea, cyanosis, inability to lie flat, pink frothy sputum, and widespread dry and wet crackles in both lungs. Without prompt treatment, it can be fatal. It is a severe complication of advanced mitral stenosis and is often triggered by strenuous physical activity, emotional stress, infections, sudden-onset tachyarrhythmias, pregnancy, or labor.

Thromboembolism

It occurs in 20% of patients, with 80% of these cases associated with atrial fibrillation. 2/3 of systemic embolisms involve the cerebral arteries, while the remainder involves peripheral arteries and visceral arteries (e.g., splenic, renal, and mesenteric arteries).

Rarely, a pedunculated or free-floating thrombus in the left atrium may obstruct the mitral valve orifice, leading to sudden death. Emboli originating from the right atrium can cause pulmonary embolism.

Right Heart Failure

It is a common late-stage complication. In right heart failure, right ventricular output is significantly reduced, pulmonary blood flow decreases, and left atrial pressure drops. Additionally, thickening of the alveolar and pulmonary capillary walls may reduce dyspnea and the risk of acute pulmonary edema and massive hemoptysis. However, this comes at the cost of decreased cardiac output, with clinical manifestations of right heart failure symptoms and signs.

Pulmonary Infections

They are common due to elevated pulmonary venous pressure and pulmonary congestion, which increase susceptibility to lung infections. These infections can precipitate heart failure.

Infective Endocarditis

It is rare, particularly in patients with significant leaflet calcification or atrial fibrillation.

Treatment

General Management

Patients should avoid excessive physical exertion and strenuous exercise and undergo regular follow-ups. Asymptomatic patients with severe mitral stenosis or those who have undergone successful percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty (PBMV) should have annual clinical and echocardiographic evaluations. Once symptoms develop, interventional or surgical treatment should be considered promptly. For patients with mild to moderate stenosis, follow-up intervals may be extended to every 2-3 years.

Medical Therapy

Patients with active rheumatic fever should receive anti-rheumatic treatment, and long-term or even lifelong benzathine penicillin prophylaxis is recommended to prevent recurrence of rheumatic fever.

Symptomatic improvement can be achieved with diuretics, beta-blockers, digoxin, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and ivabradine.

For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), anticoagulation therapy is required. For those with moderate to severe MS, vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are preferred over novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), with an international normalized ratio (INR) target of 2-3.

For patients in sinus rhythm, anticoagulation is recommended if they have a history of thromboembolism, left atrial thrombus, a left atrial diameter >50 mm or volume >60 mL/m2, or spontaneous echo contrast detected on transesophageal echocardiography.

Management of Complications

Massive Hemoptysis

Patients should be seated upright, and sedatives and intravenous diuretics should be administered to lower pulmonary artery pressure.

Acute Pulmonary Edema

Management principles are similar to pulmonary edema caused by acute left heart failure. Specific considerations include:

- Vasodilators that primarily reduce afterload by dilating small arteries should be avoided; instead, nitrates that reduce preload by dilating the venous system should be used.

- Positive inotropic agents are generally ineffective for pulmonary edema caused by MS. Intravenous digoxin may be administered to slow the ventricular rate in AF with a rapid ventricular response.

Atrial Fibrillation

For acute rapid AF, immediate ventricular rate control is necessary. Intravenous digoxin (e.g., lanatoside C) can be administered first. If the response is inadequate, intravenous diltiazem or esmolol may be used.

In hemodynamically unstable patients (e.g., those with pulmonary edema, shock, angina, or syncope), immediate electrical cardioversion is required.

For chronic AF, interventional or surgical treatment of the stenosis should be pursued. Medications such as beta-blockers, digoxin, and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be used to control the ventricular rate, alongside VKA anticoagulation.

Interventional Therapy

Indications for percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty (PBMV):

- Severe isolated mitral stenosis (MS)

- Pliable valve leaflets with good mobility, without significant calcification or subvalvular thickening (Wilkins echocardiographic score ≤8)

- Absence of intracardiac thrombus

- No associated mitral regurgitation or other valvular diseases

- No active rheumatic activity

- Presence of clear clinical symptoms with NYHA functional class II-III heart failure

For symptomatic MS patients with a mitral valve area >1.5 cm2, PBMV may still be performed at experienced comprehensive valve disease centers if the pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) >25 mmHg or the mean transvalvular pressure gradient >15 mmHg during exercise. If mild mitral regurgitation is present, PBMV is only suitable for cases without left ventricular enlargement.

PBMV is also an option for older patients, those with severe coronary artery disease or other severe comorbidities such as pulmonary, renal, and oncological diseases who are unsuitable for or decline surgery, pregnant women with severe dyspnea, and patients with restenosis after prior surgical commissurotomy.

For patients with thrombus or chronic atrial fibrillation, adequate pre-procedural anticoagulation with warfarin is required.

Contraindications include:

- Mitral valve area >1.5 cm2

- Recent history of thromboembolism (within the past 3 months)

- Moderate to severe mitral regurgitation

- Severe or bilateral commissural calcification

- Non-fused commissures

- Severe aortic or tricuspid valve disease

- Coronary artery disease requiring bypass surgery

- Significantly enlarged right atrium

- Severe thoracic deformities

For patients with left atrial thrombus, if the surgery is not an emergency, anticoagulation therapy for 2-6 months should be administered, followed by a repeat transesophageal echocardiography. If the thrombus resolves, PBMV can be performed; if the thrombus persists, surgical treatment should be considered.

PBMV has a success rate of 95.2%-99.3%, with immediate improvement in symptoms and hemodynamics. Major complications include:

- Death (0.12%)

- Moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (1.41%)

- Cardiac tamponade (0.81%)

- Thromboembolism (0.48%)

Surgical Treatment

Mitral Valve Replacement (MVR)

Mitral valve replacement is an option for patients with severe mitral stenosis (MS) who are unsuitable for balloon valvuloplasty.

Indications include:

- Patients with severe MS and significant symptoms (NYHA Class III-IV) who are at low surgical risk, are unsuitable for PBMV, or have failed previous PBMV

- Patients with moderate MS combined with other cardiac conditions requiring surgery

- Patients with severe MS who experience recurrent thromboembolic events despite adequate anticoagulation therapy

Surgery should ideally be performed in symptomatic patients without pulmonary hypertension. Severe pulmonary hypertension increases surgical risks but is not an absolute contraindication, as pulmonary hypertension often improves postoperatively.

Contraindications include:

- Cerebral embolism: As cerebral embolism is a common complication of rheumatic MS, surgery is generally delayed for 2-3 months to avoid potential cerebral damage from cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative anticoagulation complications.

- Poor overall condition: Patients with severe systemic conditions who cannot tolerate surgery have a significantly increased surgical risk and postoperative mortality, making them unsuitable for surgical treatment.

- Active rheumatic activity: Persistent rheumatic myocarditis suggests ongoing rheumatic activity, and elective surgery is usually delayed for 3-6 months after controlling the rheumatic condition.

- Small left ventricle: In patients with long-standing severe MS and recurrent rheumatic activity, chronic disuse of the left ventricle may lead to severe atrophy and myocardial fibrosis. These patients have a high risk of developing low cardiac output syndrome and severe arrhythmias postoperatively, making surgery extremely risky.

The mortality rate and postoperative complications for MVR are higher than for commissurotomy. However, survivors generally experience significant improvement in cardiac function.

Open Mitral Commissurotomy

This procedure is suitable for patients with surgical indications but with severe valve calcification, extensive chordal fusion and shortening, left atrial thrombus, or restenosis.

Under cardiopulmonary bypass, the fused commissures, chordae tendineae, and papillary muscles are separated. Calcified plaques on the valve leaflets are removed, and thrombi in the left atrium are cleared.

This procedure results in significant hemodynamic improvement, low surgical mortality, and fewer postoperative complications. Lifelong anticoagulation is not required. However, due to a high recurrence rate, open commissurotomy is being gradually phased out.

Prognosis

The prognosis is poor for patients with symptomatic mitral stenosis, atrial fibrillation, chronic heart failure with cardiac enlargement, or a history of embolism.

Before surgical treatments were available, the 10-year survival rate was 84% for asymptomatic patients, 42% for those with mild symptoms, and 15% for those with moderate to severe symptoms. The average time from symptom onset to complete disability was 7.3 years.

Surgical treatment has significantly improved quality of life and survival rates.