Rheumatic fever is one of the major causes of valvular heart disease. It is caused by infection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GAS), and its pathogenesis is related to an abnormal immune response secondary to the streptococcal infection.

The bacterial capsule shares common antigens with joints and synovial membranes. The M protein and M-associated proteins in the bacterial cell wall, as well as N-acetylglucosamine in the middle layer polysaccharides, share antigens with cardiac muscle and heart valves. The cell membrane lipoproteins share antigens with myocardial fiber membranes and the hypothalamic and caudate nuclei. After streptococcal infection, the anti-streptococcal antibodies produced in the body can form circulating immune complexes with these shared antigens. These immune complexes deposit in the synovial membranes, myocardium, heart valves, hypothalamic nuclei, or caudate nuclei, activating complement components and causing inflammatory lesions, which lead to corresponding clinical manifestations.

Clinical Manifestations

Acute rheumatic fever typically occurs 2-6 weeks after an episode of streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis. It usually presents with acute onset, though a subclinical course is also possible. Patients often exhibit moderate, irregular fever along with anorexia, diaphoresis, fatigue, and pallor.

Arthritis primarily affects large joints (knees, ankles, wrists, and elbows). It is migratory, polyarticular, and does not leave permanent joint deformities. Symptoms typically resolve within a few weeks.

Carditis is the most common manifestation of rheumatic fever in children. The younger the patient, the higher the likelihood of cardiac involvement. Myocarditis and endocarditis are the most common forms, though pericarditis may also occur. Mild cases may be asymptomatic, while severe cases can lead to heart failure. Myocarditis can cause cardiac enlargement, diffuse apical impulses, tachycardia disproportionate to fever, muffled heart sounds, and gallop rhythm. A systolic murmur at the apex may be heard. In 75% of cases, a diastolic decrescendo murmur is heard over the aortic valve. ECG findings may include prolonged PR intervals, ST-T changes, and arrhythmias. Endocarditis primarily affects the mitral valve, followed by the aortic valve, leading to valvular insufficiency. This results in symptoms and signs such as a pansystolic murmur radiating to the axilla (mitral regurgitation) and a diastolic decrescendo murmur at the left sternal border (aortic regurgitation). In the acute phase, valvular damage is typically characterized by congestion and edema, which resolve during recovery. However, recurrent episodes can lead to permanent scarring and rheumatic valvular heart disease. Pericarditis often coexists with myocarditis and endocarditis, forming pancarditis. Early cases with minimal effusion may present with precordial pain and pericardial friction rub. ECG may show widespread ST-segment elevation with a downward convexity. Large effusions may lead to absent precordial pulsations, muffled heart sounds, jugular venous distension, hepatomegaly, and signs of cardiac tamponade. Chest X-rays may show a flask-shaped cardiac silhouette, and echocardiography can confirm pericardial effusion.

It may be accompanied by chorea, subcutaneous nodules, and erythema marginatum. Patients with chorea generally have a good prognosis, with spontaneous recovery occurring within 4-6 weeks, though a small number may have residual neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Diagnosis

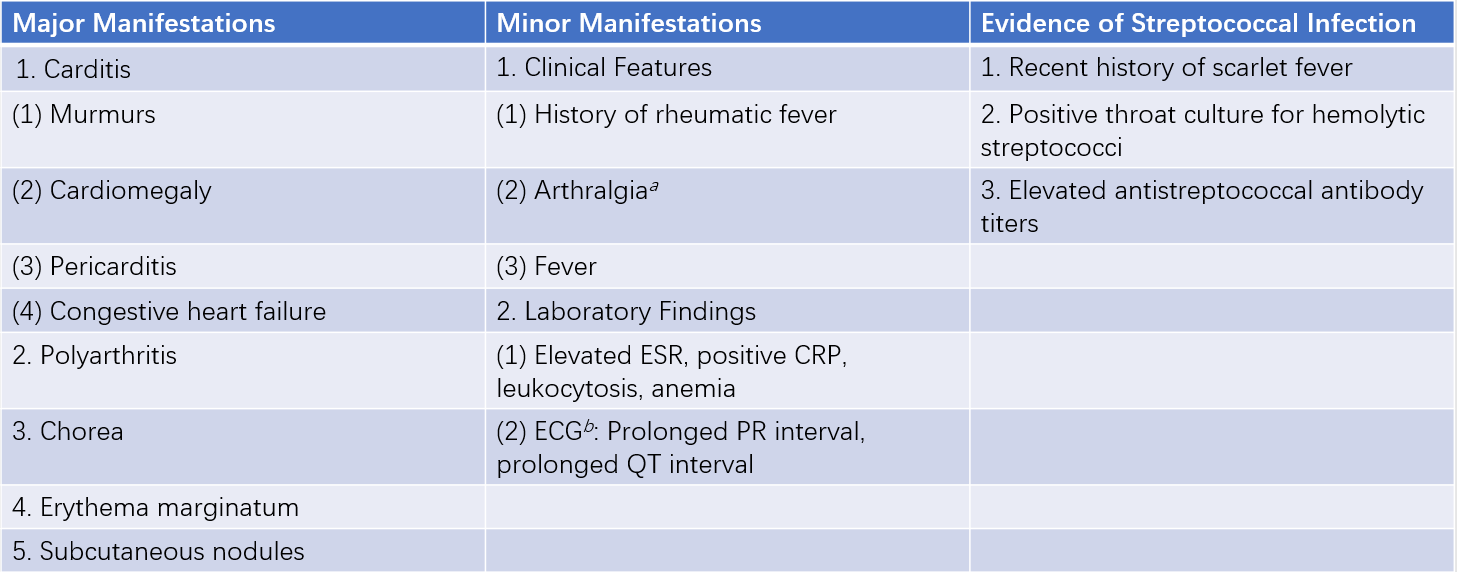

The diagnosis of rheumatic fever is based on the revised Jones criteria. Evidence of preceding streptococcal infection is required, along with either:

- Two major manifestations, or

- One major manifestation and two minor manifestations

Major manifestations:

- Carditis (e.g., pleuritic chest pain, pericardial friction rub, heart failure, or mitral regurgitation)

- Polyarthritis

- Chorea

- Erythema marginatum

- Subcutaneous nodules

Minor manifestations:

- Fever

- Arthralgia

- A history of rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease

Table 1 Revised Jones diagnostic criteria

Notes:

a, If arthritis is listed as a major manifestation, arthralgia cannot be considered a minor manifestation.

b, If carditis is listed as a major manifestation, ECG findings cannot be considered a minor manifestation.

Diagnostic criteria:

If there is evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection and either two major manifestations or one major manifestation plus two minor manifestations are present, acute rheumatic fever is highly suspected.

However, in the following three situations, if no other cause for the symptoms is identified, strict adherence to the above diagnostic criteria is not necessary:

- When chorea is the sole clinical manifestation.

- When carditis presents insidiously or develops slowly.

- In patients with a history of rheumatic fever or existing rheumatic heart disease, who are at high risk of recurrence of rheumatic fever upon reinfection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Treatment

Patients with carditis should remain on bed rest until fever normalizes, tachycardia resolves, and ECG findings improve. Rest should continue for 3-4 weeks before resuming physical activity. Patients with arthritis can begin activity once fever and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) normalize.

Penicillin 400,000-600,000 U intramuscularly twice daily, or benzathine penicillin (600,000 U for children under 27 kg, 1,200,000 U for those over 27 kg) intramuscularly once every 2-4 weeks can be administered. For penicillin-allergic patients, erythromycin, roxithromycin, lincomycin, or quinolones can be used.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first choice. Aspirin is commonly used at a dose of 80-100 mg/kg/day for children or 3-4 g/day for adults, divided into 3-4 doses. The dose is tapered in 2 weeks, with a treatment course of 4-8 weeks.

Early use of corticosteroids is recommended. Prednisone is given at an initial dose of 30-40 mg/day for adults or 1.0-1.5 mg/kg/day for children, divided into 3-4 doses. The dose is tapered in 2-4 weeks, with a treatment course of 8-12 weeks.

Aspirin should be added 2 weeks before discontinuing corticosteroids to prevent rebound symptoms.

Sedatives such as diazepam or phenobarbital may be used.

Low-dose digitalis, diuretics, and vasodilators may be used, along with correction of electrolyte imbalances.

Prevention

Primary prevention includes improving socioeconomic conditions, enhancing living environments, preventing malnutrition, promoting physical exercise to strengthen the body, protecting against cold and damp environments, actively preventing upper respiratory tract infections, and providing health education to children and adolescents about the association between streptococcal pharyngitis and rheumatic fever. Additionally, regular screening of high-risk and susceptible populations should be conducted, along with the use of an effective anti-streptococcal vaccine.

Secondary prevention aims to prevent the recurrence of rheumatic fever or the development of secondary rheumatic heart disease. This involves intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin (1.2 million units) once every 3-4 weeks. The duration of prophylaxis should be at least 5 years, preferably continuing until the age of 25. For patients with rheumatic heart disease, the prophylaxis period should last at least 10 years, until the age of 40, or even for a lifetime. For individuals allergic to penicillin, oral erythromycin can be used as an alternative, taken for 6-7 days each month, with the same duration as mentioned above.

Prognosis

The prognosis of rheumatic fever depends on the severity of myocarditis, whether the initial episode was adequately treated, and whether secondary prevention measures were implemented. Approximately 70% of patients recover within 2-3 months. Acute carditis affects about 65% of patients, and without timely treatment, 70% may develop valvular heart disease. Chorea has a good prognosis, with most cases resolving spontaneously within 4-10 weeks, though a few may have residual neuropsychiatric symptoms.