Acute pericarditis refers to an acute inflammatory disease of the visceral and parietal layers of the pericardium. It is commonly characterized by chest pain, pericardial friction rub, electrocardiographic changes, and pericardial effusion leading to pericardial fluid accumulation. It may occur as an isolated condition or as a manifestation of systemic diseases involving the pericardium.

Etiology

The most common cause of acute pericarditis is viral infection. Other causes include bacterial infections, connective tissue diseases, tumors, uremia, post-myocardial infarction pericarditis, aortic dissection, chest wall trauma, post-cardiac surgery, and hypothyroidism. In some cases, the cause remains undetermined after evaluation, which is referred to as idiopathic acute pericarditis or acute nonspecific pericarditis.

Pathophysiology

Acute pericarditis may present as serous, fibrinous, hemorrhagic, or purulent in nature. The degree and type of inflammatory response depend on the underlying cause and the body's reaction. The subepicardial myocardium may also be involved.

Clinical Manifestations

In cases caused by viral infections, symptoms often occur in adults aged 18-30 years, typically 1-2 weeks after the onset of infection. Some patients may also present with clinical signs of pneumonia and pleuritis.

Symptoms

Retrosternal or precordial pain is a hallmark of acute pericarditis, commonly observed during the fibrinous exudative phase. The pain may radiate to the neck, left shoulder, back, upper abdomen, jaw, left forearm, or hand. It can be severe and sharp, resembling a stabbing pain, and is often related to respiratory movements. It is typically exacerbated by coughing, deep breathing, changes in posture, or swallowing. As the disease progresses, symptoms may shift from chest pain during the fibrinous phase to dyspnea during the effusive phase. In some cases, moderate to large pericardial effusion may lead to cardiac tamponade, causing symptoms such as dyspnea, restlessness, edema, and even shock. Infectious pericarditis may be accompanied by fever and fatigue.

Signs

The most diagnostic physical sign of acute pericarditis is a pericardial friction rub, which is a high-frequency, scratchy, and rough sound. A typical friction rub consists of three components corresponding to atrial contraction, ventricular contraction, and ventricular relaxation. It is most prominent in the precordial region, particularly at the left sternal border in the 3rd-4th intercostal spaces, the lower sternum, and the xiphoid area. The intensity of the friction rub may vary with respiration and posture and may become more pronounced when the patient leans forward, lies prone, takes a deep breath, or when firm pressure is applied with the stethoscope. The friction rub may persist for hours, days, or even weeks. When the effusion increases and separates the two pericardial layers, the apical impulse weakens, the cardiac dullness boundary expands, the friction rub disappears, and heart sounds become distant and muffled. If partial adhesion occurs between the pericardial layers, friction rubs may still be heard despite significant pericardial effusion.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory findings depend on the underlying disease. In infectious pericarditis, leukocytosis, elevated neutrophil counts, increased C-reactive protein levels, and accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rates are common. In viral or idiopathic pericarditis, as well as acute myocardial infarction, elevated troponin levels may be observed. Connective tissue diseases may show positive immunological markers, and patients with uremia may exhibit significantly elevated creatinine levels.

Electrocardiography (ECG)

ECG is a key diagnostic tool for acute pericarditis, with approximately 60%-90% of cases showing changes. These changes typically occur within hours to days after the onset of chest pain and include:

- ST-segment elevation with a concave upward pattern in all standard leads except aVR and V1, where ST-segment depression may be observed. These changes usually resolve within hours to days.

- Return of the ST segment to baseline after a few days.

- Gradual appearance of T-wave inversion, which may normalize within weeks to months or persist for a prolonged period.

- Re-appearance of upright T waves.

- Sinus tachycardia is common, and PR-segment depression may be observed in all leads except aVR and V1. In cases of large pericardial effusion, electrical alternans of the QRS complex may occur.

Chest X-ray

Chest X-rays may appear normal. If significant pericardial effusion is present, an enlarged cardiac silhouette may be observed. Effusions of less than 250 mL in adults or 150 mL in children are typically undetectable by X-ray.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography can confirm the presence of pericardial effusion, estimate its volume, and help determine whether hemodynamic changes are due to cardiac tamponade. Echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis can improve the success rate and safety of the procedure.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Cardiac MRI provides detailed visualization of the volume and distribution of pericardial effusion, helps differentiate the nature of the effusion, and measures pericardial thickness. Delayed enhancement imaging may show pericardial enhancement, which is sensitive for diagnosing pericarditis. For acute myocarditis and pericarditis, it also aids in assessing myocardial involvement.

Pericardiocentesis

The primary indications for pericardiocentesis include cardiac tamponade or pericarditis of unknown etiology. Pericardial fluid can be subjected to routine, biochemical, microbiological (e.g., bacterial or fungal), and cytological analyses. In cases of large effusions causing cardiac tamponade, therapeutic pericardiocentesis can relieve symptoms, and intrapericardial drug administration may be used to treat the underlying cause.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

Acute onset, characteristic chest pain, presence of pericardial friction rub, and electrocardiographic changes such as typical ST-segment elevation and/or PR-segment depression are key diagnostic features. Echocardiography confirms the diagnosis and assesses the volume of effusion. Laboratory tests showing elevated inflammatory markers, combined with relevant medical history, systemic manifestations, and additional diagnostic evaluations, contribute to identifying the underlying cause.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute pericarditis needs to be differentiated from other conditions causing acute chest pain. For patients with chest pain and ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography, differentiation from acute myocardial infarction is essential. Acute pericarditis often presents with a history of upper respiratory infection, and the pain is position-dependent, whereas myocardial infarction is typically associated with ST-segment elevation in contiguous leads with a convex upward pattern, and dynamic ST-T changes may occur within hours. For patients with hypertension and chest pain, aortic dissection with aneurysmal rupture should be excluded. Aortic dissection is characterized by tearing pain of greater severity, often located retrosternally or in the back, with radiation to the lower extremities. If the rupture extends into the pericardial cavity, electrocardiographic changes resembling acute pericarditis may be observed, and echocardiography aids in diagnosis, while enhanced CT reveals the site of rupture. Differentiation from pulmonary embolism is also necessary. Pulmonary embolism is more common in patients with prolonged immobility or limited mobility and may present with chest pain, dyspnea, or even syncope, along with reduced oxygen saturation. D-dimer levels are usually elevated. Electrocardiographic findings may include a deepened S-wave in lead I, a prominent Q-wave in lead III, and inverted T-waves in lead III, along with possible ST-T changes. Echocardiography may show increased right heart pressure or volume as indirect evidence of pulmonary embolism, while pulmonary artery CTA or pulmonary angiography is required for confirmation. After diagnosing acute pericarditis, further differentiation of the underlying cause is necessary to guide treatment.

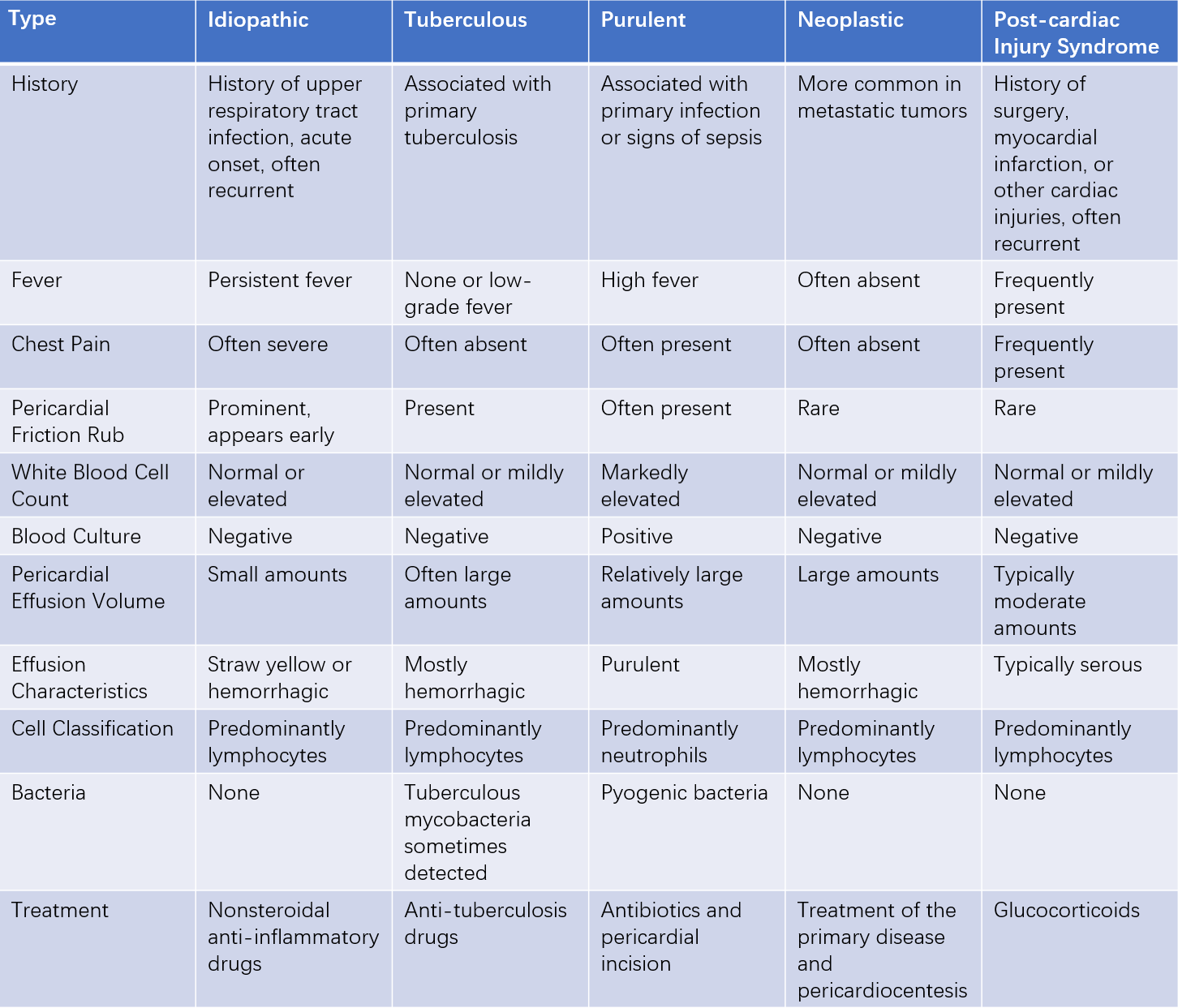

Table 1 Differential diagnosis and treatment of common types of pericarditis

Note: Based on echocardiographic findings, the width of the anechoic zone in the pericardial cavity can be used to classify the volume of pericardial effusion: small (<10 mm), moderate (10-20 mm), and large (>20 mm).

Prognosis

The prognosis of acute pericarditis depends on its etiology. Idiopathic acute pericarditis is a self-limiting disease with a relatively short course, and many patients experience no significant complications, leading to a favorable long-term prognosis. However, when associated with conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, malignant tumors, or systemic lupus erythematosus, the prognosis is poor.

Treatment

Treatment includes addressing the underlying cause, relieving cardiac tamponade, and providing symptomatic and supportive care. Patients are recommended to remain on bed rest until chest pain resolves and fever subsides. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin (750-1,000 mg, three times daily) can be used for pain relief. If ineffective, alternatives such as ibuprofen (300-800 mg, three times daily), indomethacin (25-50 mg, three times daily), or colchicine (0.6 mg, twice daily, or adjusted based on body weight) may be administered. Once effective, aspirin doses can be reduced by 250-500 mg every 1-2 weeks, and ibuprofen doses can be reduced by 200-400 mg every 1-2 weeks. Dosages can be adjusted according to the severity of symptoms and the patient's sensitivity to the medication. Treatment duration is typically 1-2 weeks or until symptoms improve and laboratory markers return to normal. In cases of severe pain, opioid analgesics may be used. For patients with persistent effusion unresponsive to other treatments, glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone 40-80 mg once daily) may be considered. Immediate pericardiocentesis is required for acute cardiac tamponade caused by significant pericardial effusion. For patients with refractory recurrent pericarditis lasting more than two years, recurrent pericardial effusion requiring repeated drainage, inadequate response to glucocorticoid therapy, or severe chest pain, surgical pericardiectomy may be considered.

Prevention

Preventing viral infections, enhancing physical fitness, and improving immune function are important measures. During the acute phase, bed rest and close monitoring of disease progression are recommended, with particular attention to changes in pericardial effusion. Timely intervention is necessary when disease progression is detected.