Etiology

Various cancer treatment drugs can cause cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) of varying severity. Common causes of CTRCD include the following:

Anthracycline-Related CTRCD

Anthracyclines (e.g., doxorubicin) are commonly used chemotherapeutic agents for treating solid tumors (e.g., breast cancer) and hematologic malignancies (e.g., lymphoma, acute leukemia). These drugs can induce myocardial injury through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, iron metabolism disorders, calcium overload, and inhibition of topoisomerase IIβ, leading to DNA damage. Anthracycline-related CTRCD is positively correlated with cumulative dosage, but it is important to note that this toxicity can occur even with the first dose, as there is no absolute safe dosage. Based on the time of onset, CTRCD can be categorized as acute (occurring within hours or days after administration), chronic (occurring within one year after administration), or late-onset (occurring years after administration). Chronic and late-onset CTRCD are often irreversible.

HER-2 Targeted Therapy-Related CTRCD

HER-2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) targeted therapies include monoclonal antibodies (e.g., trastuzumab, pertuzumab), small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., lapatinib), and antibody-drug conjugates. The primary mechanisms of CTRCD caused by HER-2 targeted therapies are believed to include HER-2 pathway inhibition, excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and impaired myocardial repair. CTRCD associated with HER-2 targeted therapies typically occurs during treatment or within a few months after treatment ends and is not significantly correlated with cumulative dosage. This type of CTRCD is usually reversible after discontinuation of the therapy, with few long-term complications.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (ICI)-Related CTRCD

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can be classified into three main categories:

- PD-1 (programmed cell death protein-1) inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab.

- PD-L1 (programmed cell death-ligand 1) inhibitors, such as atezolizumab.

- CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4) inhibitors, such as ipilimumab.

- LAG-3 (lymphocyte activation gene-3) antibodies, such as relatlimab.

ICIs can lead to myocarditis and heart failure. The incidence of ICI-related myocarditis ranges from 0.06% to 3.80%, with a high mortality rate of 39.7% to 66.0%. The exact mechanism of ICI-related CTRCD remains unclear but may involve the activation of T lymphocytes by ICIs, which recognize shared antigens between myocardial cells and tumors, triggering autoimmune lymphocytic myocarditis. Risk factors for ICI-related myocarditis include combination therapy (e.g., two ICIs, ICIs combined with chemotherapy, or ICIs combined with anti-angiogenic agents), diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, pre-existing cardiovascular disease, obesity, or advanced age.

CAR-T Cell Therapy-Related CTRCD

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, primarily used for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and aggressive B-cell lymphoma, can cause CTRCD. It may also be associated with arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, and cardiac arrest. These cardiovascular toxicities are thought to be related to cytokine release syndrome.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation-Related CTRCD

The risk of cardiovascular disease is significantly increased following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The main mechanisms include:

- Cardiovascular toxicity from cancer therapies associated with HSCT (e.g., anthracycline-based regimens, mediastinal radiotherapy, total body irradiation, or cyclophosphamide-based conditioning regimens).

- Graft-versus-host disease.

- Severe infections, such as sepsis.

The risk of CTRCD is higher in the presence of pre-existing cardiovascular disease or associated risk factors.

Additionally, other chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., antimetabolites, taxanes, platinum-based drugs) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors (e.g., bevacizumab) can also lead to CTRCD.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms and signs of CTRCD are consistent with those of heart failure.

Auxiliary Examinations

Echocardiography

A reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) greater than 10% from baseline or an LVEF below 50% during treatment suggests the presence of CTRCD. Global longitudinal strain (GLS), measured using two-dimensional speckle tracking technology, has higher sensitivity and can detect CTRCD earlier. A decrease in GLS of more than 15% from baseline indicates CTRCD.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR)

CMR is capable of assessing myocardial edema and fibrosis with high accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity. It is useful for the early diagnosis of CTRCD and serves as one of the primary diagnostic tools for ICI-related myocarditis.

Cardiac Biomarkers

Cardiac biomarkers include cTnI/TnT and BNP/NT-proBNP. Early myocardial injury caused by cancer therapy can be detected through elevated cTnI/TnT levels before a significant decline in LVEF occurs. BNP/NT-proBNP can assist in the diagnosis of CTRCD.

Endomyocardial Biopsy

Endomyocardial biopsy provides histological evidence of structural and pathological changes in the heart and is considered the gold standard for diagnosing CTRCD. For example, ICI-related myocarditis may present as multifocal inflammatory cell infiltration accompanied by myocardial cell necrosis. However, as an invasive procedure, myocardial biopsy is limited in its routine clinical application.

Diagnosis

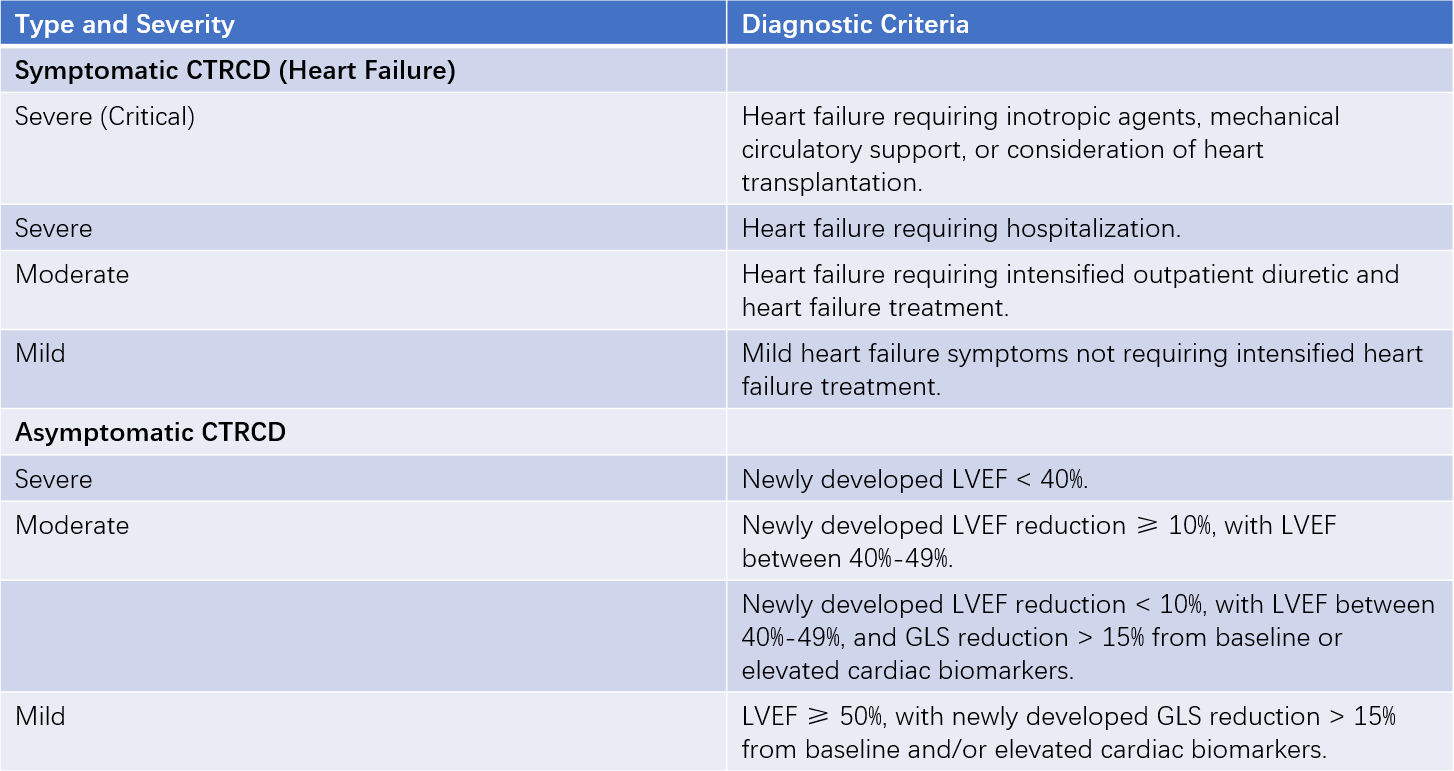

Diagnostic criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Classification and diagnostic criteria for CTRCD

Assessment and Monitoring

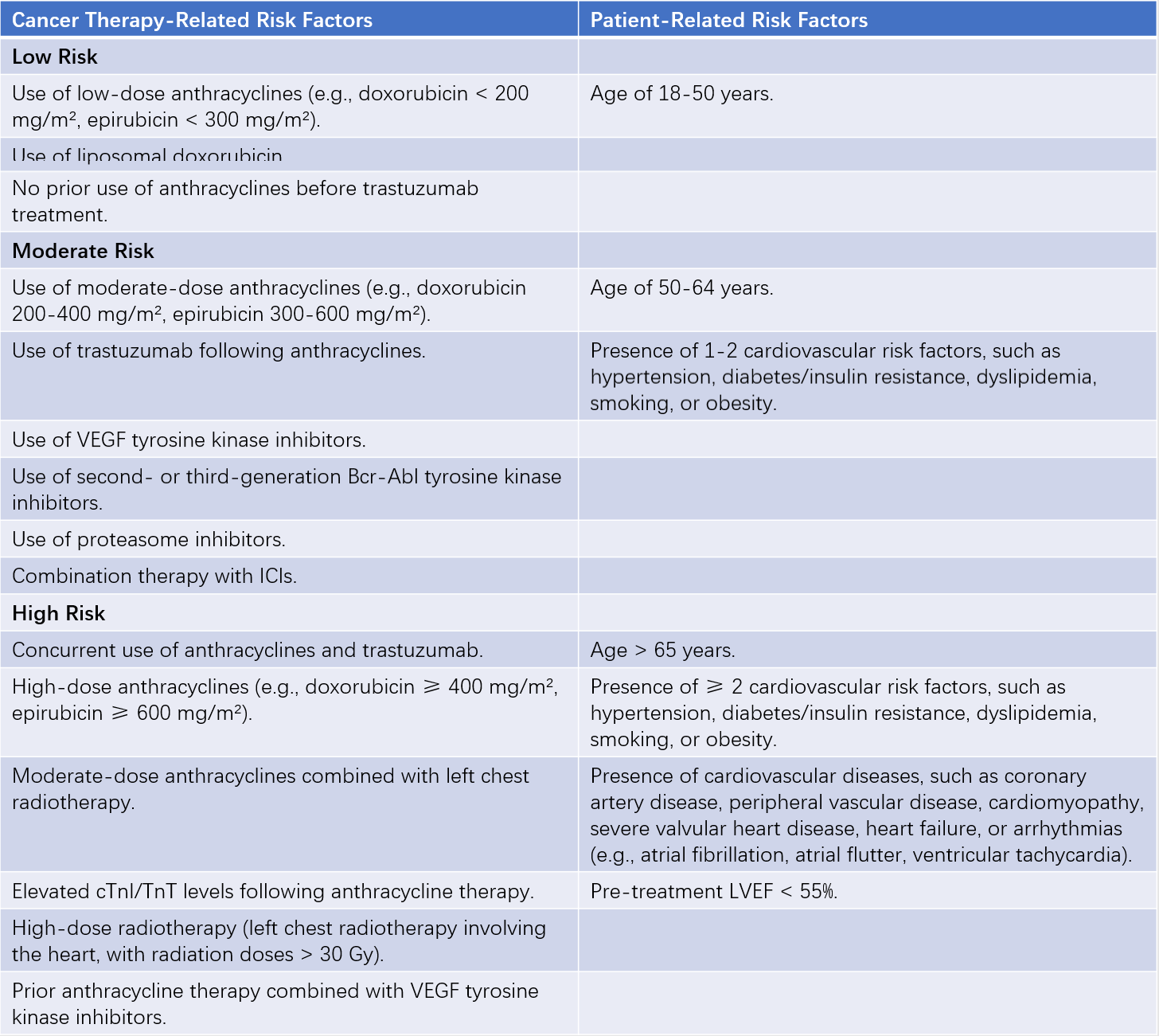

Prevention is prioritized over treatment in managing CTRCD in cancer patients. All patients should undergo baseline risk assessment before initiating cancer therapy to identify those at moderate or high risk early. High-risk patients should receive primary prevention with ACE inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or beta-blockers. During cancer therapy, individualized monitoring plans should be developed based on baseline risk stratification. Long-term follow-up is recommended after cancer therapy to achieve comprehensive, lifelong management of CTRCD in cancer patients.

Table 2 Baseline risk factors and risk stratification for CTRCD

Note: Meeting any one of the cancer therapy-related or patient-related risk factors qualifies for the corresponding risk stratification level.

Treatment

Patients with symptomatic CTRCD or asymptomatic moderate-to-severe CTRCD should be treated with ACEIs/ARBs/ARNIs, beta-blockers, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. For mild, asymptomatic CTRCD, the use of ACEIs/ARBs and/or beta-blockers should be considered, while cancer therapy may continue uninterrupted.

For anthracycline-induced CTRCD, if continued anthracycline-based chemotherapy is considered, measures such as dose reduction, switching to liposomal doxorubicin, or using dexrazoxane in addition to ACEIs/ARBs and beta-blockers may help reduce the risk of CTRCD.

For patients with ICI-related myocarditis, glucocorticoids are the first-line treatment in addition to symptomatic management. Other treatment options include immunosuppressants (e.g., mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus), small molecule targeted drugs (e.g., tofacitinib), immunoglobulins, and non-pharmacological therapies such as plasmapheresis.