Chronic gastritis refers to chronic inflammatory lesions of the gastric mucosa caused by various factors and is commonly encountered in clinical practice. Its prevalence generally increases with age and is particularly common in middle-aged and older individuals. Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection is the most common cause. Currently, gastroscopy and histopathological examination of biopsy samples are the primary methods for diagnosing and differentiating chronic gastritis.

Classification

There are numerous classification methods for chronic gastritis. In clinical practice, it is primarily divided into chronic superficial gastritis (currently referred to as chronic non-atrophic gastritis), chronic atrophic gastritis, and special types of gastritis. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the ICD-11 disease classification, in which chronic gastritis is categorized mainly by etiology into ten types, including autoimmune gastritis and Hp-associated gastritis.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Hp Infection

Hp enters the stomach via the oral route. Some bacteria are killed by gastric acid, while others attach to the mucus layer of the gastric antrum. Using its flagella, Hp penetrates the mucus layer and resides on the surface of the gastric antral epithelial cells, generally without invading the gastric glands or lamina propria. This allows Hp to avoid the bactericidal effects of gastric acid while also evading clearance by the host immune system.

Hp produces urease, which breaks down urea into ammonia, creating a localized microenvironment that neutralizes gastric acid and facilitates Hp colonization and proliferation, leading to chronic infection.

Hp causes cellular damage through the production of ammonia and vacuolating cytotoxin. It promotes the release of inflammatory mediators by epithelial cells and triggers autoimmune responses through Lewis X and Lewis Y antigens on its cell wall. These mechanisms prolong or exacerbate the inflammatory response. The progression of gastric mucosal inflammation depends on a combination of factors, including the strain and virulence of Hp, individual host differences, and the gastric microenvironment.

Alkaline Duodenal Reflux

Chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa may result from long-term alkaline duodenal reflux caused by gastrointestinal motility disorders, hepatobiliary diseases, or distal gastrointestinal obstructions.

Medications and Toxins

The use of NSAIDs (e.g., aspirin) or even selective COX-2 inhibitors is a common cause of reactive gastropathy. Many toxins can also damage the gastric mucosa, with ethanol being the most common. Rapid ethanol intake often results in submucosal hemorrhage observed during endoscopy, although biopsy typically shows no significant mucosal inflammation. The combined effects of ethanol and NSAIDs produce even greater damage to the gastric mucosa.

Autoimmune Mechanisms

Parietal cells in the gastric body secrete not only hydrochloric acid but also a glycoprotein known as intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor binds to vitamin B12 (extrinsic factor) from food to form a complex that prevents enzymatic digestion and facilitates absorption in the ileum. When autoantibodies against parietal cells or intrinsic factor develop, an autoimmune inflammatory response reduces the number of parietal cells, leading to glandular atrophy, decreased gastric acid secretion, and reduced intrinsic factor levels. This impairs vitamin B12 absorption, resulting in megaloblastic anemia, known as pernicious anemia. This condition is more common in Northern Europe.

Age-Related Factors and Others

Similar to other organs, the gastric mucosa undergoes degenerative changes with aging. In addition, the high prevalence of Hp infection in older adults reduces the regenerative capacity of the gastric mucosa, leading to chronic inflammation, glandular atrophy, and metaplasia.

Endoscopy and Histopathology

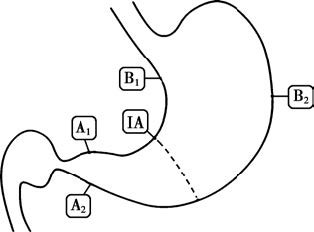

On endoscopy, the mucosa of chronic non-atrophic gastritis may appear hyperemic and edematous, with swollen and thickened mucosal folds. In atrophic gastritis, the mucosa may appear pale, with thinning and flattening of the folds, reduced mucus secretion, and a thinner mucosal layer, sometimes revealing submucosal vascular patterns. The updated Sydney classification for gastritis, along with the Operative Link for Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) and Operative Link for Gastritis Intestinal Metaplasia (OLGIM) systems introduced in recent years, recommend that at least five biopsy samples be taken during endoscopy, with specific locations as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Biopsy sites for the diagnosis of chronic gastritis

A1–A2: Lesser and greater curvature of the antrum, mucus-secreting glands.

IA: Lesser curvature of the gastric angle, a common site for early atrophy and intestinal metaplasia.

B1–B2: Anterior and posterior walls of the gastric body, acid-secreting glands.

The histological changes in chronic gastritis, resulting from mucosal damage and repair caused by different etiologies, are as follows:

Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is characterized by infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The severity of inflammation is graded as mild, moderate, or severe based on the depth of inflammatory cell infiltration. Due to the patchy distribution of H. pylori infection, inflammation in the gastric antral mucosa also tends to have a multifocal distribution and is often accompanied by lymphoid follicles. Active inflammation is marked by the presence of neutrophils, which are found in the lamina propria, foveolar epithelium, and glandular epithelium. In severe cases, neutrophils may form crypt abscesses.

Atrophy

Atrophy involves extension of the lesion into the deep glands, resulting in glandular destruction, reduced glandular number, and fibrosis of the lamina propria. Atrophy is classified into non-metaplastic atrophy and metaplastic atrophy based on the presence or absence of metaplasia. Multifocal atrophy, centered around the gastric angle and extending to the antrum and body, increases the risk of gastric cancer.

Metaplasia

Chronic inflammation over time may result in the replacement of the gastric mucosal surface epithelium and glands by goblet cells and pyloric gland cells. A wider distribution or greater severity of metaplasia is associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer. Gastric gland metaplasia is classified into two types:

- Intestinal Metaplasia (IM): Characterized by the replacement of gastric glands with intestinal glands containing goblet cells.

- Pseudopyloric Metaplasia: Proliferation of mucous neck cells in acid-secreting glands forms pyloric gland-like structures. These are histologically similar to pyloric glands and require biopsy location for differentiation. The risk associated with intestinal metaplasia may be assessed using subtyping when necessary (refer to the gastric cancer chapter).

Dysplasia

Also referred to as atypical hyperplasia, dysplasia involves excessive proliferation and loss of differentiation during the regeneration of epithelial cells. The proliferating epithelial cells appear crowded, stratified, with enlarged nuclei lacking polarity, increased mitotic figures, and disorganized glandular structures. The term "intraepithelial neoplasia" (IEN) is recommended by the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer. Low-grade IEN is roughly equivalent to low-grade dysplasia, whereas high-grade IEN includes severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Dysplasia is considered a precancerous lesion of gastric cancer. Mild dysplasia may often regress to normal, while severe dysplasia can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, warranting close monitoring.

In the progression from chronic inflammation to gastric cancer, premalignant conditions include atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia.

Clinical Manifestations

Most patients exhibit no obvious symptoms, and even when symptoms are present, they are often non-specific. Symptoms may include epigastric discomfort, bloating, dull pain, or burning pain, along with dyspeptic symptoms such as loss of appetite, belching, acid regurgitation, and nausea. The severity of symptoms does not correlate well with endoscopic or histopathological findings. Physical signs are typically absent, though mild tenderness in the epigastrium may occasionally be observed. Patients with autoimmune gastritis and associated pernicious anemia often present with systemic weakness, fatigue, significant loss of appetite, weight loss, anemia, and neurological symptoms such as symmetrical numbness in the distal extremities, unsteady gait, and other peripheral neuropathies, while gastrointestinal symptoms are relatively mild.

Patients with NSAID-induced gastritis (including aspirin) are often asymptomatic or may experience only mild epigastric discomfort or vague pain. In critically ill patients with stress-related gastritis, symptoms may be masked by the underlying primary disease, but upper gastrointestinal bleeding may occur, presenting as sudden hematemesis and/or melena as the initial symptom.

Diagnosis

Gastroscopy and histological examination are essential for the diagnosis of chronic gastritis, as clinical symptoms alone are insufficient for a definitive diagnosis. The etiology can be determined through a combination of medical history and laboratory testing, including:

Hp Testing

Details can be found in the relevant chapters.

Serological Testing

Measurement of serum anti-parietal cell antibodies, intrinsic factor antibodies, pepsinogen (PG) I and II levels and their ratio, gastrin-17, and vitamin B12 levels aids in the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis. For suspected gastric neuroendocrine tumors, gastrin-34 or total gastrin levels may be assessed.

Treatment

Most adults have mild non-atrophic gastritis (superficial gastritis) of the gastric mucosa. If Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is negative, there is no erosion, and the patient is asymptomatic, medication may not be necessary. For chronic gastritis involving the full thickness of the mucosa or presenting with active inflammation, as well as in cases with precancerous conditions such as intestinal metaplasia, pseudopyloric metaplasia, atrophy, or dysplasia, short-term or intermittent long-term treatment may be considered.

Etiological Treatment

Hp-Associated Gastritis

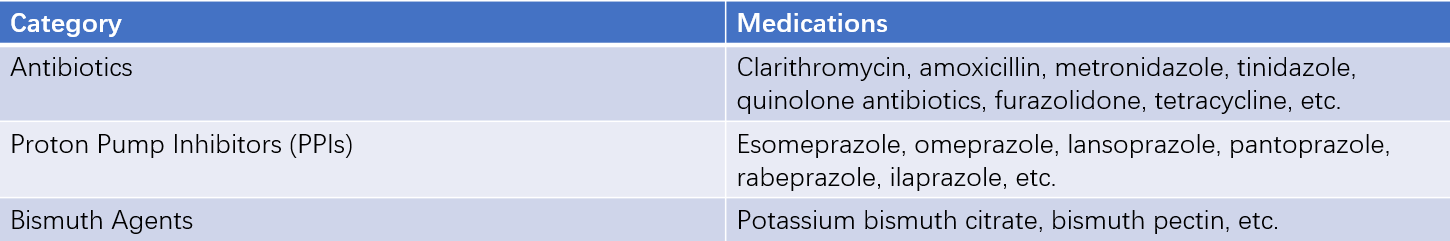

None of the drugs listed in Table 1 are effective in eradicating Hp when used alone. These antibiotics cannot exert their antimicrobial effects properly in an acidic environment and require the combined use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to suppress gastric acid for optimal efficacy. The currently recommended regimen is a bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, which includes one PPI, two antibiotics, and one bismuth agent, administered for 10–14 days. The choice of antibiotics and treatment duration should be based on local antibiotic resistance patterns.

Table 1 Drugs with bactericidal and inhibitory effects on H. pylori

Duodenogastric Reflux

Medications that protect the gastric mucosa and improve gastrointestinal motility may be used.

Deficiency of Gastric Mucosal Nutritional Factors

Supplementation with multivitamins is recommended. For patients with pernicious anemia, lifelong vitamin B12 injections are necessary.

Symptomatic Treatment

Acid-suppressing or neutralizing medications may be used to alleviate symptoms. Prokinetic agents or digestive enzyme preparations can help relieve symptoms such as bloating caused by impaired gastric motility or enzyme deficiency. Mucosal protective agents may help reduce abdominal pain and acid reflux.

Management of Precancerous Conditions

After eradicating Hp, appropriate supplementation with multivitamins and selenium-containing medications may be considered. For focal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (including severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ) that cannot be reversed with medication, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) can be performed. Regular follow-up should be conducted based on the patient's condition.

Patient Education

Hp is primarily transmitted within households. Practices that may lead to mother-to-child transmission, such as pre-chewing food, should be avoided. The use of separate tableware is encouraged to reduce the risk of Hp infection. A diverse diet is recommended, avoiding picky eating and ensuring adequate nutrition. Moldy food should be avoided, and the consumption of smoked, pickled, or nitrate/nitrite-rich foods should be minimized. Fresh food intake should be increased. Rough, strongly flavored, spicy, or irritating foods, as well as excessive long-term alcohol consumption, should be avoided. Smoking cessation is advised. Maintaining a positive psychological state and ensuring adequate sleep are also important.

Prognosis

The prognosis of chronic non-atrophic gastritis is generally favorable. Intestinal metaplasia is usually difficult to reverse. Some cases of atrophy may improve or reverse. Mild dysplasia may regress to normal, but severe dysplasia is more likely to progress to cancer. Patients with a family history of gastric cancer, a monotonous diet, or frequent consumption of smoked or pickled foods should be closely monitored for the progression of intestinal metaplasia, atrophy, and dysplasia to gastric cancer.