Gastric cancer refers to malignant tumors originating from epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa, with the vast majority being adenocarcinomas. These account for more than 95% of all malignant gastric tumors. Globally, gastric cancer ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Infectious Factors

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection shares similar epidemiological characteristics with gastric cancer. Populations in high-incidence areas for gastric cancer exhibit a higher prevalence of Hp infection, and individuals with positive Hp antibodies have a higher risk of developing gastric cancer compared to those who are antibody-negative. In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) under the WHO classified Hp infection as a Group I (definite) human carcinogen. Additionally, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and other infectious agents may also contribute to the development of gastric cancer.

Environmental and Dietary Factors

The incidence of gastric cancer decreased by approximately 25% among the first-generation Japanese immigrants to the United States, 50% among the second generation, and eventually reached levels similar to the local U.S. population by the third generation. This indicates that environmental factors play a significant role in the development of gastric cancer. Risk factors include high-salt diets, nitrite consumption, tobacco use (e.g., snuff), low intake of fresh vegetables, and excessive alcohol consumption. Other contributing factors include volcanic soil regions, high peat soil content, excessive nitrates in water and soil, imbalances in trace elements, and chemical pollution, which may directly or indirectly promote gastric cancer through dietary exposure.

Genetic Factors

Approximately 10% of gastric cancer patients have a family history of the disease. Individuals with a family history of gastric cancer, particularly those with first-degree relatives affected by the disease, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or juvenile polyposis, have a 2–3 times higher risk of developing gastric cancer compared to the general population. A small proportion of gastric cancers are classified as "hereditary gastric cancer syndromes" or "hereditary diffuse gastric cancer." Diffuse-type gastric cancer demonstrates a stronger familial aggregation, suggesting a closer association with genetic factors.

During the development and progression of gastric cancer, certain molecular events may play a role, including DNA aneuploidy, loss or suppression of tumor suppressor gene expression (e.g., TP53, FHIT, APC, DCC, CDKN2A, and CDH1), and overexpression of specific genes (e.g., MT-CO2, MST1R, and VEGFA).

Precancerous Changes

Also referred to as premalignant conditions, these are divided into precancerous diseases (precancerous states) and precancerous lesions. Precancerous diseases refer to benign gastric conditions associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer, while precancerous lesions refer to pathological changes with a higher likelihood of malignant transformation, primarily dysplasia.

Intestinal Metaplasia, Atrophic Gastritis, and Dysplasia

Intestinal metaplasia can be classified into three types based on epithelial cell characteristics and mucus secretion: type I (complete intestinal metaplasia), type II (incomplete small intestinal metaplasia), and type III (incomplete colonic metaplasia). Theoretically, type II and especially type III intestinal metaplasia carry a higher risk of gastric cancer.

For dysplasia, despite various international classification and staging systems, the 2019 WHO criteria remain widely used. Dysplasia is graded into five levels, with low-grade and high-grade dysplasia (or intraepithelial neoplasia) being the most significant.

Gastric Polyps

Gastric polyps occur in 0.8%–2.4% of the population. Among these, 50% are fundic gland polyps, 40% are hyperplastic polyps, and only 10% are adenomas. Fundic gland polyps larger than 1 cm have a cancer transformation rate of less than 1%. Hyperplastic polyps, although rarely malignant, may undergo malignant transformation in areas of intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia, potentially forming well-differentiated intestinal-type gastric cancer. Adenomas, however, have a higher risk of malignant transformation.

Remnant Gastritis

Malignant transformation typically occurs 20 years after surgery for benign gastric conditions. Compared to Billroth I gastrectomy, the risk of malignancy is four times higher after Billroth II gastrectomy.

Gastric Ulcers

Malignant transformation may result from inflammation, erosion, regeneration, and dysplasia at the ulcer margins.

Ménétrier’s Disease

Case reports indicate that 15% of individuals with this condition are associated with gastric cancer.

Clinically, gastric cancer can be broadly categorized into intestinal and diffuse gastric cancer. According to Correa's hypothesis, under the influence of Hp infection, adverse environmental factors, and unhealthy dietary habits, the gastric mucosa progresses from chronic inflammation to atrophic gastritis, atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and eventually to intestinal gastric cancer. During this process, the normal balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis in the gastric mucosa is disrupted. Molecular events associated with gastric cancer development include microsatellite instability, inactivation of tumor suppressor genes due to deletion or hypermethylation, and amplification of certain oncogenes or related genes.

Pathology

Gastric cancer most commonly occurs in the antrum, followed by the cardia and the body of the stomach. It is classified into early and advanced stages based on the depth of invasion. Early gastric cancer refers to lesions confined to the mucosa or submucosa, regardless of whether there is regional lymph node metastasis. Histologically, it is characterized by high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma. Advanced gastric cancer invades beyond the submucosa. Tumors invading the muscularis propria are considered mid-stage gastric cancer, while those involving the serosa or extending beyond it are classified as late-stage gastric cancer. Pathological staging follows the TNM classification system established by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Histopathology of Gastric Cancer

The WHO categorizes gastric cancer into several types, including adenocarcinoma (papillary, tubular, mucinous, mixed, and hepatoid adenocarcinoma), adenosquamous carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma. Based on the degree of differentiation, gastric cancer is further classified into well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated types.

Invasion and Metastasis

Gastric cancer spreads through four primary mechanisms:

Direct Extension

Tumors invade adjacent organs. Cardia and fundus cancers often infiltrate the esophagus, liver, and greater omentum, while cancers of the gastric body frequently invade the greater omentum, liver, and pancreas.

Lymphatic Metastasis

Metastasis typically progresses from regional lymph nodes to distant lymph nodes. Involvement of the left supraclavicular lymph node is referred to as Virchow's node.

Hematogenous Dissemination

Hematogenous spread occurs in over 60% of advanced cases. The liver is the most common site of metastasis, followed by the lungs, peritoneum, and adrenal glands. Metastasis may also occur in the kidneys, brain, and bone marrow.

Peritoneal Seeding

Cancer cells shed into the peritoneal cavity after invading the serosa, leading to implantation on the intestinal wall and pelvic cavity. If implantation occurs in the ovaries, it is termed a Krukenberg tumor. Nodular masses may also form around the rectum.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Approximately 80% of early gastric cancer cases are asymptomatic, while some patients may experience dyspeptic symptoms. In advanced stages, the most common symptoms are weight loss (about 60%) and epigastric pain (50%), along with anemia, loss of appetite, aversion to food, and fatigue.

Complications or metastases may result in specific symptoms. Cardia cancer involving the lower esophagus may cause dysphagia. Pyloric obstruction may lead to nausea and vomiting. Ulcerative gastric cancer with bleeding can cause hematemesis or melena, followed by anemia. Liver metastases may result in right upper abdominal pain, jaundice, and/or fever. Peritoneal dissemination often presents with ascites. Rarely, lung metastases may cause cough, hiccups, or hemoptysis, while pleural involvement can lead to pleural effusion and dyspnea. Pancreatic invasion may result in radiating back pain.

Signs

Early gastric cancer typically lacks significant physical signs. In advanced stages, an abdominal mass may be palpable in the upper abdomen, often tender and located in the right upper quadrant corresponding to the gastric antrum. Liver metastases may result in hepatomegaly and jaundice, sometimes accompanied by ascites. Peritoneal metastases may also cause ascites, with positive shifting dullness. Splenomegaly may occur if the portal or splenic vein is involved. Distant lymph node metastases, such as to Virchow's node, may present as a hard, immobile mass. Rectal examination may reveal nodular masses in the rectovesical pouch.

Diagnosis

Gastroscopy

Gastroscopy combined with mucosal biopsy is the most reliable diagnostic method.

Early Gastric Cancer

Early lesions may appear as small polypoid elevations or depressions, or as flat areas with rough mucosa, patchy erythema, and erosions that bleed easily upon contact. Suspicious areas may be stained with methylene blue, with cancerous lesions showing distinct staining patterns, aiding in biopsy site selection. Advanced imaging techniques such as magnifying endoscopy, narrow-band imaging, and confocal laser endomicroscopy can detect subtle lesions and improve diagnostic accuracy for early gastric cancer. Due to the lack of characteristic endoscopic features and the small size of early lesions, meticulous observation and multiple biopsies of suspicious areas are essential.

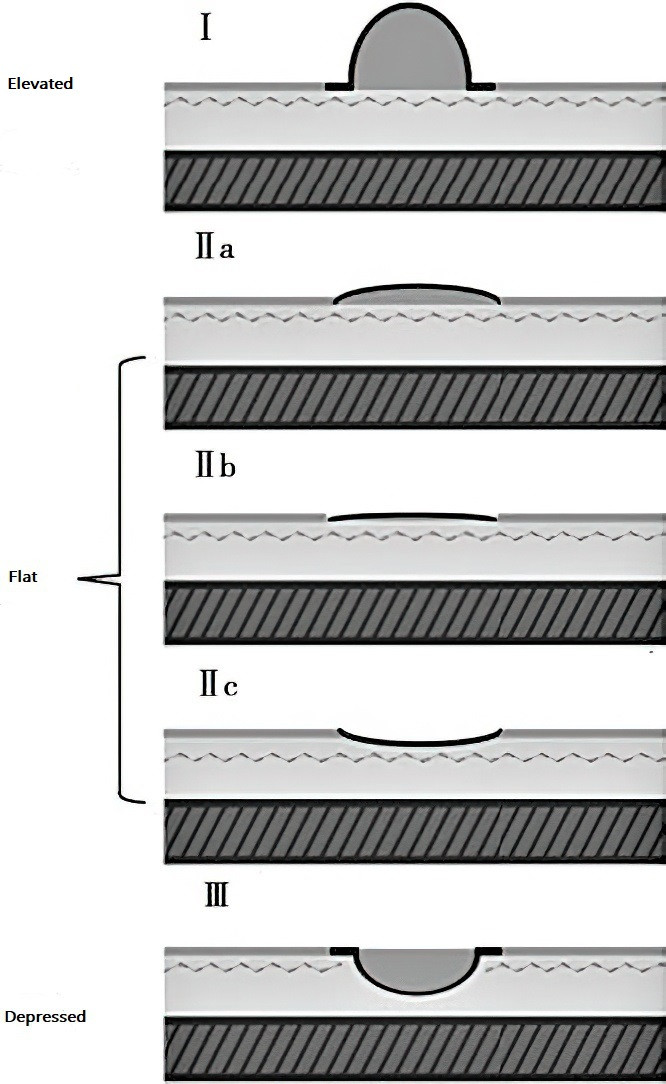

Figure 1 Endoscopic classification of early gastric cancer

Advanced Gastric Cancer

Advanced lesions are often readily identified on endoscopy. Tumors typically have an irregular surface, erosion, and dirty exudates, and they bleed easily during biopsy. They may also present as deep ulcers with necrotic grayish-white bases and nodular, raised edges without converging mucosal folds or peristalsis. Submucosal infiltration may cause diffuse thickening and hardening of the gastric wall, particularly in the antrum, leading to gastric outlet obstruction. When the entire stomach is involved, it may become rigid and thickened, a condition known as linitis plastica. Submucosal infiltrative gastric cancer, though relatively rare, may lack obvious mucosal changes on endoscopy, and even standard biopsies may yield false negatives. For ulcerative lesions, multiple biopsies from the edges and base, or large mucosal resection, can improve diagnostic yield.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can accurately assess the depth of tumor invasion, distinguish between early and advanced gastric cancer, and evaluate regional lymph node involvement. It serves as a valuable complement to CT imaging.

Laboratory Tests

Iron-deficiency anemia is common. Positive fecal occult blood tests suggest chronic low-grade bleeding from the tumor. Significant reductions in serum pepsinogen (PG) I/II ratios, OLGA or OLGIM stages III and IV, indicate high-risk populations for gastric cancer. Serum tumor markers such as CEA, CA19-9, and CA72-4 may aid in early detection and postoperative surveillance, though their specificity and sensitivity are limited. Certain fecal microbiota with high abundance may serve as potential biomarkers for early diagnosis.

X-ray and CT Imaging

In patients contraindicated for gastroscopy, X-ray barium studies may detect gastric ulcers or raised lesions, appearing as niches or filling defects, though differentiation between benign and malignant lesions is challenging. Features such as disrupted or obliterated mucosal folds, adjacent mucosal rigidity, and loss of peristalsis strongly suggest malignancy. Advances in CT imaging have improved the accuracy of clinical staging and, along with PET-CT, facilitate the assessment of tumor metastasis.

Complications

Details are consistent with those of peptic ulcers.

Treatment

For early-stage gastric cancer without lymph node metastasis, endoscopic treatment may be performed. In advanced gastric cancer without systemic metastasis, surgical treatment is an option. After tumor resection, efforts should be made to eradicate residual Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection.

Endoscopic Treatment

Early gastric cancer can be treated with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). EMR is generally indicated for intramucosal gastric cancer without lymph node metastasis confirmed by endoscopic ultrasound, including non-ulcerative lesions less than 2 cm in diameter for type IIa lesions and less than 1 cm for type IIb or IIc lesions. ESD is indicated for intramucosal intestinal-type gastric cancer of any size without ulceration, intestinal-type gastric cancer with ulceration less than 3 cm in diameter, and intestinal-type submucosal gastric cancer less than 3 cm in diameter with an invasion depth of less than 500 μm. Resected cancerous tissue should undergo pathological examination. If cancer is found at the resection margin or if superficial cancer invades the submucosa, additional surgical treatment may be necessary.

Surgical Treatment

For early gastric cancer, partial gastrectomy may be performed. In advanced gastric cancer without distant metastasis, radical resection should be pursued whenever possible. For cases with distant metastasis or obstruction, palliative surgery may be performed to maintain gastrointestinal continuity. Surgical resection combined with regional lymph node dissection is currently the main treatment for advanced gastric cancer. The extent of gastrectomy includes proximal gastrectomy, distal gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy, with digestive tract continuity restored using Billroth I, Billroth II, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reconstruction. For patients who cannot be cured surgically, particularly those with obstruction, partial tumor resection may relieve symptoms in approximately 50% of cases.

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally not required for early gastric cancer without metastasis. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery can shrink tumors, increasing the chances of radical resection and cure. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy includes intravenous chemotherapy, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, continuous hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion, and lymphatic-targeted chemotherapy. Monotherapy is suitable for early-stage patients requiring chemotherapy or for those unable to tolerate combination therapy. Commonly used drugs include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), tegafur (FT-207), mitomycin C (MMC), doxorubicin (ADM), cisplatin (DDP) or carboplatin, nitrosoureas (CCNU, MeCCNU), and etoposide (VP-16). Combination chemotherapy often involves 2–3 drugs to minimize toxic side effects. Chemotherapy failure is often associated with cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents or multidrug resistance.

Other Treatments

In addition to radiotherapy and anti-angiogenic targeted therapy, immunotherapy has emerged as a novel treatment option in clinical practice. Immune checkpoint inhibitors achieve tumor cell destruction by modulating T-cell activity within the tumor microenvironment. These inhibitors include cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors, programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors, and programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, all of which have shown some efficacy in the treatment of gastric cancer.

Prognosis

The prognosis of gastric cancer is directly related to the stage at diagnosis. To date, because most gastric cancers are diagnosed at intermediate or advanced stages, the 5-year survival rate ranges from approximately 7% to 34%.

Prevention

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) in individuals with high-risk factors for gastric cancer may help prevent its development.

High-risk populations should undergo regular follow-up using endoscopy and serum pepsinogen I/II measurements.

Aspirin, COX-2 inhibitors, statins, antioxidants (including multivitamins and the trace element selenium), and green tea may have some preventive effects.

Adopting healthy lifestyle habits and actively treating precancerous conditions may reduce the risk of gastric cancer.