Intestinal tuberculosis is a chronic, specific infectious disease of the intestines caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, often secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis. In recent years, the incidence of this condition has increased due to factors such as the rising prevalence of HIV infection and the widespread use of immunosuppressants and biologics, which have led to weakened immunity in certain populations.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Over 90% of cases of intestinal tuberculosis are caused by the human strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection occurs through ingestion of sputum containing the bacteria due to respiratory tuberculosis or through sharing meals with individuals with active pulmonary tuberculosis. As an acid-fast bacterium, M. tuberculosis is resistant to gastric acid and often causes lesions in the ileocecal region after entering the gastrointestinal tract. This is due to the following reasons:

- Tuberculous intestinal contents tend to remain longer in the ileocecal region, increasing the chance of local mucosal infection.

- The ileocecal region contains abundant lymphatic tissue, which is susceptible to bacterial invasion.

In rare cases, infection with the bovine strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can occur through the consumption of contaminated milk or dairy products. The disease can also result from hematogenous dissemination, as seen in miliary tuberculosis, or from direct spread of tuberculosis lesions in the abdominal or pelvic cavity.

Pathology

The ileocecal region is the most commonly affected site in intestinal tuberculosis, though the terminal ileum and the colon and rectum may also be involved. The immune response and hypersensitivity of the host to varying quantities and virulence of M. tuberculosis lead to different pathological features.

Ulcerative Intestinal Tuberculosis

The lymphoid tissue and isolated lymphoid follicles in the intestinal wall are primarily affected. The lesions initially present as congestion and edema, progressing to caseous necrosis and forming ulcers with irregular margins and varying depths. The lesions may involve the surrounding peritoneum or adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes, leading to localized tuberculous peritonitis or lymph node tuberculosis. Adhesions between the affected intestinal segment and surrounding tissues are common, reducing the likelihood of acute perforation. Chronic perforation is rare but may result in intra-abdominal abscesses or intestinal fistulas. During the healing process, fibrosis and scar formation can cause intestinal strictures. Due to obliterative endarteritis at the ulcer base, massive hemorrhage is uncommon.

Hypertrophic Intestinal Tuberculosis

Lesions are often localized to the ileocecal region, with significant granulomatous and fibrous tissue proliferation in the submucosa and serosa, leading to thickening and rigidity of the intestinal wall. Tumor-like masses may also protrude into the intestinal lumen. These changes can result in intestinal narrowing and obstruction.

Mixed Intestinal Tuberculosis

This type exhibits features of both ulcerative and hypertrophic intestinal tuberculosis.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of intestinal tuberculosis are non-specific and vary depending on the pathological characteristics of the intestinal lesions.

Abdominal Pain

Pain is often localized to the right lower abdomen or the periumbilical region, occurring intermittently and worsening after meals. It is frequently accompanied by abdominal rumbling and relieved after defecation or passing gas. These symptoms may be related to gastrointestinal reflexes triggered by eating or to intestinal spasms and obstruction caused by the passage of intestinal contents through inflamed, narrowed segments.

Changes in Bowel Habits

Ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis is often associated with diarrhea, with stools appearing mushy and without tenesmus. Alternating diarrhea and constipation may occur in some cases. Constipation is more common in hypertrophic intestinal tuberculosis. Gastrointestinal bleeding is rare but may occur in a small number of patients.

Abdominal Mass

A mass is often palpable in the right lower abdomen, with a medium texture, relative fixation, and mild to moderate tenderness. This is more common in hypertrophic intestinal tuberculosis, though ulcerative cases may also present with abdominal masses due to adhesions between affected intestinal segments, adjacent bowel, and mesenteric lymph nodes.

Systemic Symptoms and Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis

Symptoms of tuberculous toxemia are more common in ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis and include prolonged irregular low-grade fever, diaphoresis, weight loss, anemia, fatigue, and loss of appetite. If active extrapulmonary tuberculosis is present, the fever may present as remittent or persistent.

Common complications include intestinal obstruction and concurrent tuberculous peritonitis.

Laboratory and Other Examinations

Laboratory Tests

An accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is commonly observed and can serve as an indicator of tuberculosis activity. Stool samples may show small amounts of pus cells and red blood cells. A strongly positive tuberculin test or a positive interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can aid in the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis.

Imaging Studies

CT/MRI imaging of the intestines often reveals lesions located near the ileocecal region, with minimal involvement of the jejunum. Findings may include central necrosis or calcification of abdominal lymph nodes. In ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis, barium enema X-rays may demonstrate rapid clearance of barium from the affected intestinal segment, poor filling of the lesion, and good filling in the segments above and below the lesion, referred to as Stierlin's sign. In hypertrophic tuberculosis, nodular changes in the intestinal mucosa, narrowing of the intestinal lumen, shortening and deformation of the intestinal segment, and loss of the normal ileocecal angle may be observed.

Colonoscopy

Endoscopic findings may include mucosal hyperemia and edema, annular ulcers, fixed opening of the ileocecal valve, inflammatory polyps, and intestinal stricture. Biopsy of the lesion can confirm the diagnosis if granulomas, caseous necrosis, or acid-fast bacilli are identified. Positive results from polymerase chain reaction (TB-qPCR) of mucosal tissue can also assist in diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The following conditions should raise suspicion for intestinal tuberculosis:

- Young or middle-aged patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

- Symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation, along with right lower abdominal tenderness, an abdominal mass, or unexplained intestinal obstruction, accompanied by fever, night sweats, and other symptoms of tuberculous toxemia.

- Radiographic findings, such as Stierlin's sign or other imaging evidence of ulcers, intestinal deformation, or narrowing of the intestinal lumen.

- Colonoscopic findings of inflammation, ulcers, inflammatory polyps, or intestinal stricture, predominantly in the ileocecal region.

- Strongly positive tuberculin test or positive IGRA.

Definitive diagnosis can be made if caseous granulomas are identified in intestinal mucosal biopsy specimens. The presence of acid-fast bacilli, positive TB-qPCR, or positive culture results can further support the diagnosis. In cases of strong suspicion, a clinical diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis can be made if symptoms improve significantly after 2–6 weeks of anti-tuberculosis treatment, and colonoscopic lesions show marked improvement or resolution after 2–3 months of treatment.

The differential diagnosis should include the following conditions:

Crohn’s Disease

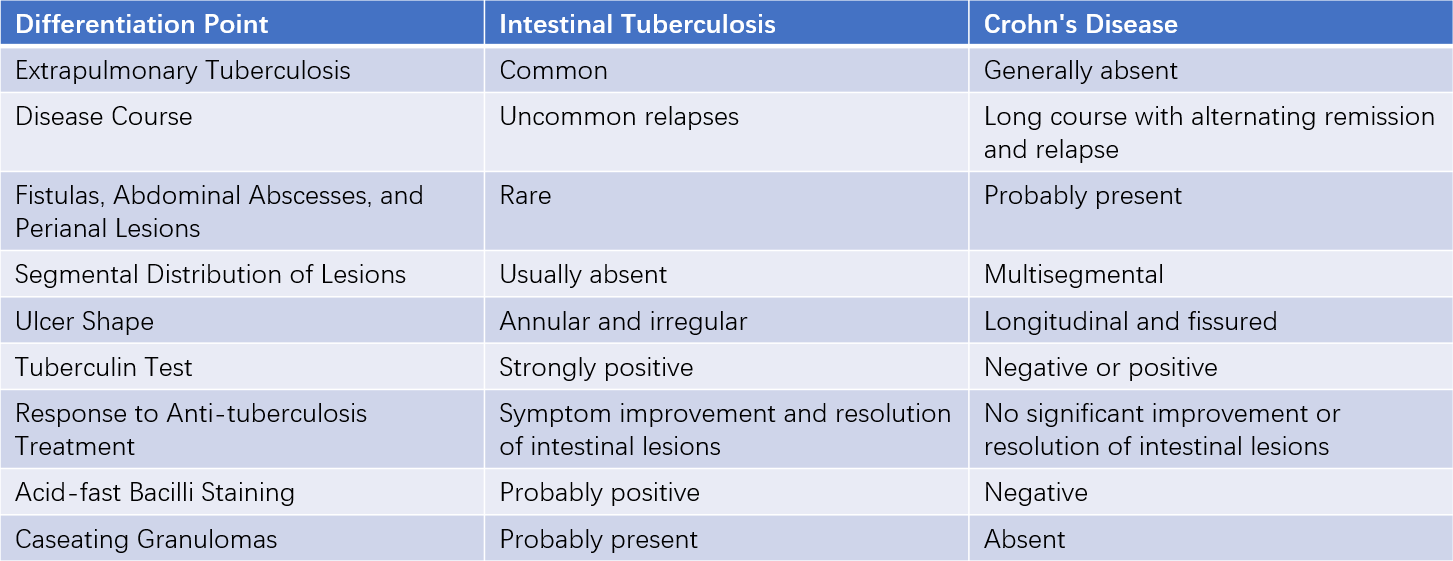

Key points for differentiation are listed in Table 1. In cases of diagnostic difficulty, empirical anti-tuberculosis treatment may be considered. Rarely, both diseases may coexist. Surgical exploration and postoperative pathology may aid in differentiation.

Table 1 Differentiation between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn's disease

Primary Intestinal Lymphoma

Clinical manifestations vary depending on the pathological subtype and are often non-specific. The diagnostic yield of endoscopic biopsy is low. Imaging may reveal significant enlargement of retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymph nodes. Immunohistochemistry can assist in diagnosis, but many cases require postoperative pathological confirmation.

Amebiasis or Schistosomal Granuloma

A history of prior infection, along with the presence of bloody-purulent stools, may suggest these conditions. Stool examination or culture may identify the causative pathogen. Colonoscopy and effective treatment with specific therapies can aid in diagnosis.

Other Conditions

Differential diagnosis should also consider right-sided colon cancer, typhoid fever, and actinomycosis.

Treatment

The goals of treatment include symptom relief, improvement of systemic conditions, promotion of lesion healing, and prevention and management of complications.

Anti-Tuberculosis Therapy

This is the cornerstone of treatment. The choice of drugs, dosing, and duration of therapy should follow established guidelines for pulmonary tuberculosis. Drug selection should balance safety, efficacy, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics, with individualized treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis emphasized.

Symptomatic Treatment

Anticholinergic drugs may relieve abdominal pain. For patients with insufficient intake or severe diarrhea, correction of water, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances is necessary. Gastrointestinal decompression may be required for patients with incomplete intestinal obstruction.

Surgical Treatment

Indications for surgery include:

- Complete intestinal obstruction or medically unresponsive incomplete obstruction.

- Acute intestinal perforation or chronic perforation with fistula formation that fails to close after medical treatment.

- Massive intestinal hemorrhage that cannot be controlled with aggressive medical intervention.

- Diagnostic uncertainty requiring exploratory laparotomy.

Patient Education

Adequate rest, prevention of secondary infections, and nutritional support are essential. Dietary recommendations should be based on the degree of intestinal obstruction, with temporary fasting or easily digestible, nutrient-rich foods as appropriate. Adherence to the full course of treatment, regular follow-up, and monitoring for adverse drug reactions are necessary.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on early diagnosis and timely treatment. Lesions in the exudative stage can heal with treatment, leading to a favorable outcome.

Prevention

Prevention includes early diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis, proper disinfection of dairy products and utensils, maintenance of good hygiene, and enhancement of overall immunity.