Ulcerative colitis (UC) is characterized by chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, and stools containing mucus, pus, and blood. It primarily affects the colon and rectum, presenting as continuous lesions. The condition is more common in young and middle-aged adults but can also occur in children or the elderly. There is no significant difference in incidence between males and females. Most cases are mild to moderate, but severe cases are not uncommon and warrant attention.

Pathology

The lesions are primarily confined to the mucosa and submucosa of the colon and rectum, with a continuous and diffuse distribution. The disease typically begins in the rectum and progresses retrogradely toward the proximal colon, potentially involving the entire colon and even the terminal ileum. During the active phase, the lamina propria of the colonic mucosa exhibits diffuse infiltration by neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Mucosal erosion, ulcers, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses are also observed. In the chronic phase, crypt architecture becomes disorganized, with glandular atrophy, distortion, irregular arrangement, and reduced numbers. Goblet cells are decreased, Paneth cell metaplasia and inflammatory polyps may occur. Since the lesions are generally limited to the mucosa and submucosa, complications such as colonic perforation, fistulas, or intra-abdominal abscesses are rare. However, in some severe cases, inflammation may involve the full thickness of the colonic wall, leading to toxic megacolon, which manifests as severe congestion of the bowel wall, colonic dilation, and thinning of the bowel wall. When ulcers extend to the muscularis or serosa, acute perforation may occur.

Clinical Manifestations

Recurrent diarrhea, stools containing mucus, pus, and blood, and abdominal pain are the main symptoms of UC. The onset is usually subacute, though some cases present acutely. The disease course is chronic, with alternating periods of exacerbation and remission. In some patients, symptoms persist and progressively worsen. The severity of the disease correlates with the extent of the lesions and clinical classification.

Digestive System Manifestations

Diarrhea and Stools Containing Mucus, Pus, and Blood

These are the most important clinical features during active disease. The frequency of bowel movements and severity of rectal hemorrhage depend on disease severity. Mild cases may involve 2–3 bowel movements per day with little to no blood in the stool, while severe cases may involve more than 10 bowel movements per day, with significant mucus, pus, and blood, or even massive rectal hemorrhage.

Abdominal Pain

Mild to moderate abdominal pain is common, often presenting as dull pain in the lower left abdomen or lower abdomen, though it may involve the entire abdomen. Patients frequently experience a sense of urgency relieved by defecation. Mild cases may have no abdominal pain or only mild discomfort, while severe cases, especially those with toxic megacolon or peritoneal involvement, may experience persistent and severe abdominal pain.

Other Symptoms

Symptoms such as abdominal distension, loss of appetite, nausea, and emesis may also occur.

Physical Signs

Mild to moderate cases may present with mild tenderness in the lower left abdomen, and sometimes a spastic descending or sigmoid colon may be palpable. Severe cases may exhibit marked abdominal tenderness. Signs such as abdominal muscle rigidity, rebound tenderness, and reduced bowel sounds suggest complications such as toxic megacolon or intestinal perforation.

Systemic Reactions

Fever

Fever is generally seen in moderate to severe cases, ranging from low to moderate-grade fevers. High fever often indicates disease progression, severe infection, or the presence of complications.

Malnutrition

Severe or persistently active cases may exhibit symptoms such as weakness, weight loss, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and disturbances in water and electrolyte balance.

Extraintestinal Manifestations

Extraintestinal manifestations include recurrent oral ulcers, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, peripheral arthritis, episcleritis, and anterior uveitis. Conditions such as sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and rare complications like amyloidosis may coexist with UC but do not always correlate with the activity of the disease itself.

Clinical Classification

UC can be classified based on disease course, severity, extent of lesions, and disease phase:

Clinical types

Clinical types include:

- Initial Onset: Refers to the first episode without a prior history.

- Chronic Relapse: The most common clinical type, characterized by alternating periods of exacerbation and remission.

Disease Phases

The disease is divided into active and remission phases. The active phase is further classified by severity:

- Mild: Bowel movements ≤3 times per day, mild or no rectal bleeding, body temperature <37.8°C, pulse <90 beats per minute, hemoglobin >105 g/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) <20 mm/h.

- Severe: Diarrhea ≥6 times per day, significant rectal bleeding, body temperature >37.8°C, pulse >90 beats per minute, hemoglobin <105 g/L, and ESR >30 mm/h.

- Moderate: Falls between mild and severe.

Extent of Lesions

Classification by the extent of lesions:

- Proctitis: Limited to the rectum.

- Left-Sided Colitis: Involves the colon distal to the splenic flexure.

- Extensive Colitis: Involves the colon proximal to the splenic flexure, potentially affecting the entire colon.

Complications

Toxic Megacolon

Toxic megacolon occurs in approximately 5% of severe UC patients. In this condition, the colonic lesions are extensive and severe, leading to reduced bowel wall tension, cessation of colonic peristalsis, and significant accumulation of intestinal contents and gas, resulting in acute colonic dilation. The transverse colon is usually the most severely affected. It is often triggered by factors such as hypokalemia, barium enema, the use of anticholinergic drugs, or opioid medications. Clinically, it manifests as a sudden worsening of the condition, marked toxemia, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances, along with abdominal distension, tenderness, and absent bowel sounds. A significant increase in white blood cell count is observed. Abdominal X-rays show colonic dilation with a loss of haustral patterns. Acute intestinal perforation may occur, and the prognosis is poor.

Malignant Transformation

Malignant transformation is more common in patients with extensive colitis and a long disease duration. The risk of developing colorectal cancer is 10–15 times higher in patients with a disease duration exceeding 20 years compared to the general population.

Other Complications

Massive colonic hemorrhage occurs in about 3% of cases. Intestinal perforation is often associated with toxic megacolon. Intestinal obstruction is rare and occurs at a much lower rate compared to Crohn's disease (CD).

Laboratory and Other Examinations

Blood Tests

Anemia, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and increased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels suggest that UC is in an active phase. If cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is suspected, serum CMV IgM and CMV DNA testing can be performed.

Stool Tests

Macroscopic examination often reveals mucus, pus, and blood. Microscopic examination shows red blood cells and pus cells. Elevated fecal calprotectin levels indicate active intestinal mucosal inflammation. Stool pathogen tests should be performed to rule out infectious colitis. If Clostridium difficile infection is suspected, confirmation can be achieved through bacterial culture, toxin detection, or PCR testing.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is one of the most important tools for diagnosing and differentiating UC. During the examination, the entire colon and terminal ileum should be observed to determine the extent of the lesions, and mucosal biopsies should be taken. However, in severe cases, full colonoscopy is not recommended, and sigmoidoscopy may be used instead to avoid exacerbating the condition or inducing toxic megacolon. UC lesions typically show continuous and diffuse distribution, starting from the rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic findings include:

- Blurred, irregular, or absent vascular patterns, mucosal congestion, edema, increased fragility, easy bleeding, and purulent exudates.

- In more severe areas, diffuse erosions and multiple shallow ulcers are observed.

- Chronic lesions often show rough mucosa with a granular appearance, inflammatory polyps, and bridging mucosa. Repeated ulcer healing and scar formation may lead to colonic deformation, shortening, flattening or loss of haustral folds.

X-ray Barium Enema

Barium enema is not routinely used but can be a supplementary diagnostic method when colonoscopy is contraindicated or incomplete. Radiographic findings include:

- Coarse or granular mucosal changes.

- Multiple shallow ulcers, appearing as irregular or serrated edges of the bowel wall with small niches, and inflammatory polyps presenting as multiple small round or oval filling defects.

- Shortened bowel segments, loss of haustral folds, and stiffened bowel walls resembling a lead pipe. Barium enema is contraindicated in severe UC patients to avoid exacerbating the condition or inducing toxic megacolon.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Patients presenting with persistent or recurrent diarrhea, mucus-pus-blood stools, abdominal pain, and tenesmus, with or without varying degrees of systemic symptoms, can be diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) after excluding infectious colitis such as chronic bacterial dysentery, amebic dysentery, chronic schistosomiasis, intestinal tuberculosis, as well as Crohn's disease (CD) of the colon, ischemic colitis, drug-induced colitis, and radiation colitis. Diagnosis is confirmed if at least one characteristic finding from colonoscopy and histological changes in mucosal biopsy are present. A complete diagnosis should include clinical type, severity, extent of lesions, disease phase, and complications. For patients with a short disease course, initial onset, or atypical clinical and colonoscopic findings, a definitive diagnosis may not be made immediately. Follow-up for 3–6 months is recommended to observe disease progression before confirming the diagnosis.

The pathological and histological changes in UC are nonspecific, as similar intestinal inflammatory changes may result from various causes. Therefore, diagnosis requires careful exclusion of other potential diseases.

UC needs to be differentiated from the following conditions:

Infectious Colitis

Bacterial Infections

Pathogens such as Shigella or Salmonella can cause symptoms like diarrhea, mucus-pus-blood stools, and tenesmus, which may resemble UC. Pathogenic bacteria can be isolated through stool cultures, and antibiotic therapy is effective.

Amebic Colitis

Lesions primarily affect the right colon but may also involve the left colon. Ulcers are deeper with undermined edges, and the mucosa between ulcers often appears normal. Examination of stool or ulcer exudates obtained via colonoscopy can identify Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites or cysts. Positive serum anti-amebic antibodies and effective anti-amebic treatment aid in differentiation.

Schistosomiasis

Patients often have a history of exposure to contaminated water and may present with hepatosplenomegaly. Stool examination can detect Schistosoma eggs, and hatching tests for miracidia are positive. Colonoscopy during the acute phase may reveal yellow-brown mucosal granules, and mucosal biopsy or histopathological examination can identify Schistosoma eggs. Serological tests for Schistosoma antibodies are also helpful.

Other Infectious Colitis

Conditions such as intestinal tuberculosis, fungal colitis, antibiotic-associated colitis, and HIV-associated colitis should also be considered.

Colonic Crohn's Disease (CD)

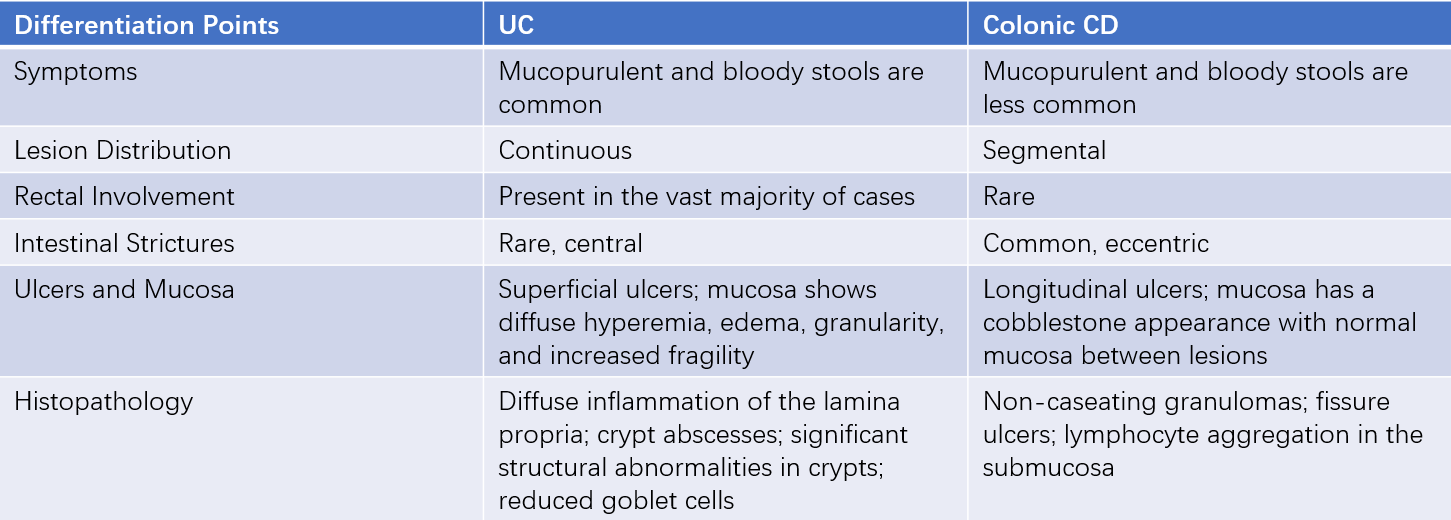

Key points for differentiating UC from CD are listed in relevant diagnostic tables. In rare cases, the two diseases may be difficult to distinguish clinically, and a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis may be made. If histological examination of the entire colon after surgical resection still cannot differentiate the two, the condition is diagnosed as unclassified colitis.

Table 1 Differentiation between UC and colonic CD

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is more common in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Rectal cancer may be detected through digital rectal examination, and colonoscopy with biopsy can confirm the diagnosis. It is important to note that UC itself increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

IBS may involve mucus in the stool but lacks pus or blood. Fecal occult blood tests are negative, and fecal calprotectin levels are typically normal. Colonoscopy reveals no evidence of organic lesions.

Other Conditions

These include drug-induced colitis, ischemic colitis, radiation colitis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, collagenous colitis, colonic polyposis, and diverticulitis.

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to induce and maintain symptom remission, promote mucosal healing, prevent complications, and improve the patient’s quality of life. Treatment strategies are chosen based on disease severity and lesion location.

Control of Inflammatory Response

Aminosalicylates

These include 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and sulfasalazine (SASP), which are used for inducing remission and maintenance therapy in mild to moderate UC. During the induction phase, 5-ASA is administered orally at 3–4 g/day. After symptom remission, the same dose or a reduced dose is used for maintenance therapy. Rectal 5-ASA enemas are suitable for lesions confined to the rectum and sigmoid colon, while suppositories are effective for rectal lesions. SASP has similar efficacy to 5-ASA but is associated with more frequent adverse effects.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are the first-line treatment for moderate cases unresponsive to 5-ASA and for severe cases. Prednisone is given orally at 0.75–1 mg/kg/day, while severe cases may initially require intravenous administration, such as hydrocortisone (200–300 mg/day) or methylprednisolone (40–60 mg/day). Once symptoms improve, methylprednisolone can be transitioned to oral administration. Glucocorticoids are used only for inducing remission during the active phase and should be tapered off gradually after symptom control. Long-term use is not recommended. During the tapering period, immunosuppressants or 5-ASA are added for maintenance therapy.

Steroid resistance refers to a failure to achieve remission after 4 weeks of treatment with prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/day.

Steroid dependence is defined as:

- The inability to reduce prednisone to ≤10 mg/day after 3 months of treatment despite maintaining remission.

- Relapse within 3 months after discontinuing steroids.

For severe UC cases unresponsive to intravenous glucocorticoids, rescue therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) monoclonal antibodies (e.g., infliximab at 5 mg/kg) or intravenous cyclosporine (2–4 mg/kg/day) may be used. Most patients achieve temporary remission and can avoid emergency surgery.

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressants are used for maintenance therapy in patients with poor response to 5-ASA, recurrent symptoms, or steroid dependence. Due to their slow onset of action, they are not used as monotherapy for inducing remission during the active phase. Commonly used agents include azathioprine and mercaptopurine. The most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal symptoms and bone marrow suppression. Before initiating treatment, it is important to test for the NUDT15 gene, which is closely related to the metabolism of purine drugs. Patients with homozygous mutations should avoid these medications. During treatment, regular monitoring of white blood cell counts is necessary. For those who cannot tolerate these drugs, methotrexate may be used as an alternative. The duration of maintenance therapy is determined based on the patient’s specific condition.

Biologics and Oral Small Molecule Drugs

Biologic agents, including anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies such as infliximab and adalimumab, anti-human α4β7 integrin monoclonal antibody vedolizumab, and anti-IL-12/IL-23 monoclonal antibody ustekinumab, as well as oral small molecule drugs like Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as upadacitinib, have demonstrated good efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission in UC. The choice of these medications should be individualized based on the patient’s condition.

Symptomatic Treatment

Water and electrolyte imbalances should be corrected promptly. Severe anemia may require blood transfusions, and hypoalbuminemia should be treated with albumin supplementation. Patients with severe disease should refrain from eating and may require total parenteral nutrition.

The use of anticholinergic drugs for abdominal pain or antidiarrheal agents such as diphenoxylate or loperamide should be approached with caution. These medications should not be used in severe cases due to the risk of inducing toxic megacolon.

For severe cases with secondary infections, active anti-infective treatment is necessary. Infections such as Clostridium difficile, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are common in patients who have been on long-term steroid or immunosuppressive therapy, potentially causing symptom recurrence or exacerbation. Timely testing and treatment are essential in such cases.

Patient Education

Patients in the active phase should ensure adequate rest, manage their emotions, and avoid excessive psychological stress.

During the acute active phase, a liquid or semi-liquid diet may be recommended. As the condition improves, a low-residue diet that is nutritious and easy to digest can be adopted. Spicy foods should be avoided. Attention to dietary hygiene is important to prevent intestinal infections.

Adherence to prescribed medications and regular follow-up appointments is essential. Medications should not be discontinued without medical advice. Patients experiencing recurrent relapses should be prepared for long-term treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Emergency surgical indications include toxic megacolon unresponsive to aggressive medical treatment, massive hemorrhage, and intestinal perforation.

Elective surgical indications include:

- Complications such as colorectal cancer.

- Poor response to medical treatment, significant drug side effects, or severe impairment of the patient’s quality of life.

The standard surgical procedure is total colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

Prognosis

UC follows a chronic course, with most patients experiencing recurrent episodes. Patients with mild disease or prolonged remission generally have a favorable prognosis. Poor prognosis is associated with severe disease, chronic persistent activity, frequent relapses, infections, complications such as toxic megacolon, or advanced age.

In recent years, advancements in treatment have significantly reduced the mortality rate. However, the risk of malignancy increases with prolonged disease duration. Patients with extensive colitis lasting more than 8 years or left-sided colitis lasting more than 15 years should undergo surveillance colonoscopy every 1–2 years, depending on their specific circumstances.