Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits, without evidence of organic disease. In addition to abdominal pain, symptoms such as bloating or abdominal discomfort are also common, often accompanied by diarrhea or constipation. Although IBS can occur at any age, it is more frequently observed in young and middle-aged adults.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

IBS results from the combined effects of visceral hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal motility abnormalities, and intestinal immune activation, leading to gut-brain interaction dysfunction.

Visceral Hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity refers to increased sensitivity of visceral tissues to stimuli. Rectal balloon distension tests have shown that IBS patients have significantly lower pain thresholds compared to control groups. Research indicates that IBS patients exhibit heightened sensitivity to physiological phenomena such as gastrointestinal distension, intestinal smooth muscle contraction, and bowel filling, which contributes to symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, and discomfort. Controlling visceral hypersensitivity can improve IBS symptoms, making it a core mechanism in IBS pathogenesis.

Gastrointestinal Motility Abnormalities

Motility abnormalities are not limited to the colon but can also involve the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, rectum, and anus. In constipation-predominant IBS, colonic transit time is prolonged. Meal stimulation increases sigmoid colon pressure amplitude in IBS patients, leading to higher frequency and amplitude of colonic propulsive movements.

Intestinal Immune Activation

Bacterial or viral infections can trigger intestinal mucosal inflammation and the release of inflammatory cytokines by immune cells, resulting in intestinal dysfunction. IBS patients show increased infiltration of inflammatory immune cells, such as mast cells, enterochromaffin cells, T lymphocytes, and neutrophils, in the intestinal mucosa. These cells release bioactive substances, inducing both systemic and localized intestinal inflammatory cytokine responses. These cytokines act on the intestinal nervous and immune systems, weakening the intestinal mucosal barrier and contributing to IBS symptoms.

Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis

IBS patients often exhibit gut microbiota imbalances, including changes in microbial diversity, mucosa-associated microbial composition, and microbial proportions. In mucosa-associated microbiota, there is an increased proportion of Bacteroides and Clostridia and a decreased proportion of Bifidobacteria. In stool samples, the proportions of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are reduced, while the ratio of facultative anaerobes, such as Streptococci and Escherichia coli, is elevated. However, the exact mechanisms by which gut microbiota imbalances contribute to IBS remain under investigation.

Psychological Disorders

Psychological factors interact with the neuroendocrine and immune systems and influence gastrointestinal motility and visceral sensitivity through gut-brain interactions, playing a role in the development of IBS.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of IBS is insidious, with symptoms that are recurrent or chronically persistent. The condition may last for years or even decades but does not affect overall physical health. Psychological and dietary factors often trigger or exacerbate symptoms. The primary clinical features include abdominal pain or discomfort, changes in bowel habits, and altered stool characteristics.

Abdominal Pain and Discomfort

Nearly all IBS patients experience varying degrees of abdominal pain, which is typically located in the lower abdomen or left lower quadrant but may occur in other areas. The pain often improves after defecation or passing gas. It rarely awakens patients from sleep.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea in IBS is typically urgent, with stools that are mushy or watery. Bowel movements occur approximately 3–5 times per day, but in severe cases during acute episodes, they may exceed 10 times per day. Mucus may be present in the stool, but there is no pus or blood.

Constipation

Constipation is often accompanied by difficulty in defecation, with stools that are hard, scant, and shaped like pellets or thin rods. Mucus may be present on the stool surface. Symptoms such as bloating and a sensation of incomplete evacuation are common.

Extragastrointestinal Manifestations

Some patients also experience symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety, depression, dizziness, and headaches.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IBS can be considered when the following criteria are met:

- Recurrent abdominal pain, bloating, or discomfort associated with defecation, accompanied by changes in stool consistency and/or frequency.

- A chronic course characterized by persistent or recurrent symptoms lasting at least 6 months, with symptoms meeting the above diagnostic criteria during the past 3 months.

- No evidence of organic, systemic, or metabolic diseases that could explain the symptoms based on routine examinations, including colonoscopy.

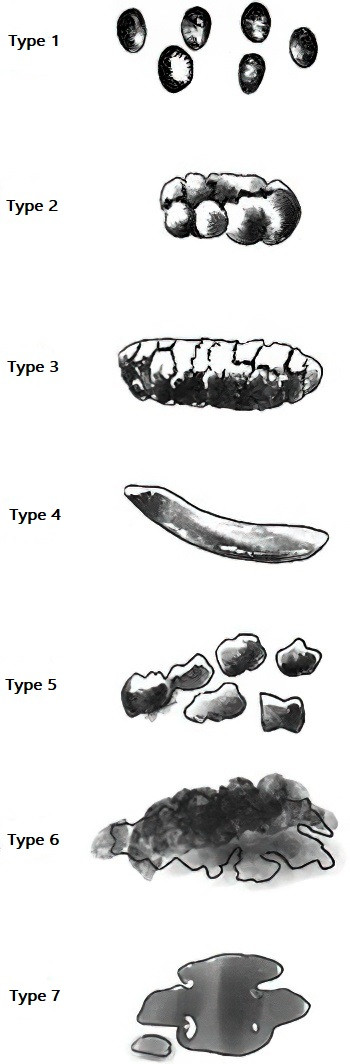

IBS is typically classified into four subtypes based on stool consistency during abnormal bowel movements, often using the Bristol Stool Form Scale (ranging from type 1, hard stools, to type 7, watery diarrhea):

- Constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C): More than 25% of stools are type 1 or 2, and less than 25% are type 6 or 7.

- Diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D): More than 25% of stools are type 6 or 7, and less than 25% are type 1 or 2.

- Mixed IBS (IBS-M): More than 25% of stools are type 1 or 2, and more than 25% are type 6 or 7.

- Unclassified IBS (IBS-U): Symptoms meet the diagnostic criteria for IBS, but stool patterns do not fit any of the above subtypes.

Figure 1 Stool form scale

Given the similarity of symptoms, IBS should be differentiated from other conditions such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life, and address patient concerns.

General Management

Establishing effective communication and a trusting relationship between the physician and the patient is fundamental to achieving satisfactory outcomes. Patients should be informed that IBS is a functional disorder that does not pose a life-threatening risk, which can help alleviate fears and concerns about the disease.

Identifying and addressing IBS triggers is an important aspect of management. Patients are encouraged to adopt a healthy lifestyle and dietary habits while avoiding foods that exacerbate symptoms.

Pharmacological Treatment

Antispasmodics

Intestinal smooth muscle antispasmodics such as pinaverium bromide, otilonium bromide, trimebutine, and alverine can selectively act on smooth muscle ion channels to relieve spasms and alleviate pain. Anticholinergic drugs may be used for short-term symptomatic relief of abdominal pain but are not suitable for long-term use.

Antidiarrheal Agents

For patients with diarrhea, antidiarrheal medications may be used as needed. Loperamide acts on opioid receptors in the intestinal wall, reducing acetylcholine release, thereby inhibiting intestinal motility, promoting water and electrolyte absorption, reducing stool frequency, and increasing stool firmness. Smectite powder can adsorb intestinal toxins, enhance intestinal mucosal absorption, and reduce the frequency of watery and mucous stools, making it a commonly used option in clinical practice.

Osmotic Laxatives

Osmotic laxatives create a hyperosmotic environment in the intestinal lumen, stimulating secretion, softening stools, and accelerating intestinal transit. Polyethylene glycol is effective in increasing spontaneous bowel movements, reducing stool hardness, and alleviating constipation symptoms in IBS-C patients.

Secretagogues

Guanylate cyclase-C agonists and selective chloride channel activators promote intestinal epithelial ion channel activity, enhancing secretion, softening stools, and improving intestinal motility. Guanylate cyclase-C agonists can also modulate visceral sensitivity, alleviating both constipation and abdominal pain in IBS-C patients.

Neurotransmitter Modulators

For patients who do not respond well to conventional treatments, neurotransmitter modulators may be considered. These medications can reduce pain perception, visceral hypersensitivity, and regulate gastrointestinal motility, effectively improving IBS symptoms. Commonly used drugs include low-dose tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Additionally, non-absorbable antibiotics (primarily rifaximin) may be used short-term to correct gut microbiota imbalances, regulate intestinal inflammation, and alleviate symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea in IBS patients. Probiotics can help modulate gut microbiota, relieving bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, with some evidence suggesting efficacy in constipation.

Psychological and Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive distortions, depression, and anxiety are common in IBS patients. For those with severe and refractory symptoms who do not respond to general or pharmacological treatments, psychological and behavioral therapies may be considered. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, stress management, and relaxation techniques.

Prognosis

IBS generally follows a benign course, with symptoms that may recur or occur intermittently, affecting quality of life.