Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is caused by an autoimmune response mediated by self-antibodies and T cells targeting hepatocytes.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The primary autoantigens involved in the pathogenesis of AIH are asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP-R) and microsomal cytochrome P450 IID6. Self-reactive T cells and antigen-presenting cells are essential components in the development of AIH. The complement system and chemokines also play a role in the humoral immune-mediated damage associated with AIH.

Clinical Manifestations

AIH is more common in females, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:5, and typically occurs between the ages of 20 and 55. Most patients experience a gradual onset, with mild cases being asymptomatic. During active disease, symptoms may include fatigue, abdominal distension, loss of appetite, pruritus, and jaundice. Early-stage findings may include hepatomegaly with tenderness, splenomegaly, and signs such as spider angiomas. Approximately 25% of patients may present with an acute onset.

During the active phase of AIH, extrahepatic manifestations are common, such as persistent fever, acute migratory polyarthritis of large joints, and erythema multiforme. AIH may overlap with other autoimmune diseases, including primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), Hashimoto's thyroiditis, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren's syndrome.

Laboratory Tests

Liver Function Tests

ALT and AST levels are typically mildly to moderately elevated.

Immunological Tests

AIH is characterized by the presence of autoantibodies and elevated IgG and/or γ-globulin levels. Autoantibodies include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (anti-SMA), perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA), anti-soluble liver antigen antibodies (anti-SLA antibodies)/anti-liver-pancreas antibodies (anti-LP antibodies), anti-actin antibodies, anti-liver kidney microsome-1 antibodies (anti-LKM-1 antibodies), and anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibodies (anti-LC-1 antibodies). These immunological changes lack specificity and may also be observed in other acute or chronic hepatitis conditions.

Pathological Examination

Histological findings considered typical of AIH include interface hepatitis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the portal areas (zone 1), rosette-like hepatocyte arrangements in the lobular areas (zone 2), and lymphocyte penetration into hepatocytes. In severe cases, bridging necrosis, multilobular necrosis, or confluent necrosis may occur. Portal inflammation generally does not involve the bile ducts, and there is no evidence of steatosis or granulomas.

Diagnosis and Clinical Subtypes

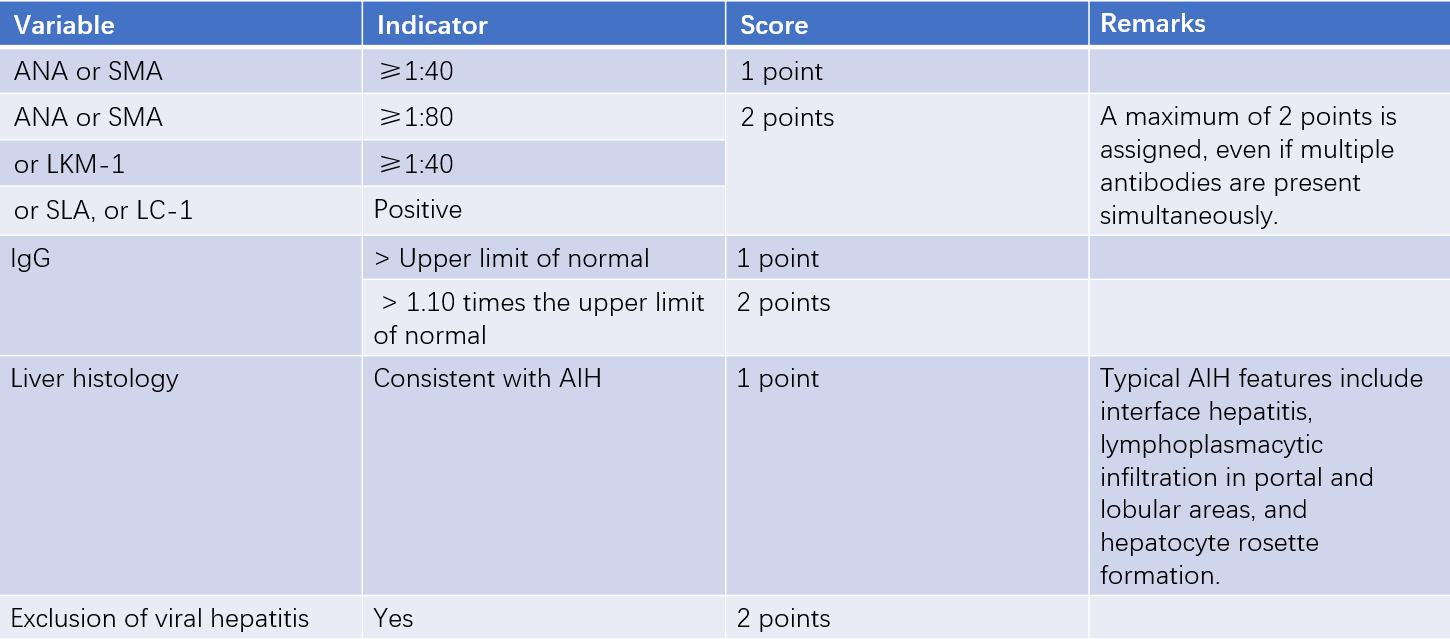

The diagnostic scoring system for AIH, shown in Table 1, aids in diagnosis. Type 1 AIH, which accounts for approximately 90% of cases, is associated with ANA or SMA positivity. Type 2 AIH, characterized by LKM-1 and/or LC-1 positivity, is more common in children. A small proportion of AIH patients are seronegative for known autoantibodies, which may indicate the presence of other undetected antibodies. AIH can be differentiated from cryptogenic chronic liver disease, as the latter does not respond to glucocorticoid therapy. AIH may coexist with other autoimmune liver diseases, such as PBC and PSC, forming what is referred to as overlap syndrome.

Table 1 Simplified AIH Diagnostic Scoring System

Note: A score of ≥6 suggests possible AIH, while a score of ≥7 confirms AIH.

Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibody; SMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; LKM-1, anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody-1; SLA, anti-soluble liver antigen; LC-1, anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibody; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; IgG, serum immunoglobulin G.

Treatment

Currently, non-specific immunosuppressive agents are the primary approach. Most patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) respond to immunosuppressive therapy. Indications for treatment include:

- Aminotransferase levels ≥3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) and IgG ≥1.5 times ULN.

- Histological findings of bridging necrosis, multilobular necrosis, or perivenular inflammation.

- Newly diagnosed AIH with ALT and/or AST ≥10 times ULN.

- Presence of coagulation abnormalities in addition to liver injury, with INR ≥1.5.

For patients not meeting these criteria, treatment decisions depend on clinical circumstances.

The treatment regimen for adults typically involves:

- Prednisone combined with azathioprine is the preferred option. Prednisone is initiated at 30–40 mg/day and tapered to 10–15 mg/day within 4 weeks. Azathioprine is administered at 50 mg/day or 1–1.5 mg/(kg·day). This combination therapy is particularly suitable for patients with postmenopausal status, osteoporosis, brittle diabetes, obesity, acne, emotional instability, or hypertension.

- High-dose prednisone monotherapy is initiated at 40–60 mg/day and tapered to 15–20 mg/day within 4 weeks. This approach is recommended for patients with AIH who have concurrent cytopenia, thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency, pregnancy, or malignancy.

- In non-cirrhotic AIH patients, budesonide may be used as an alternative to prednisone (initial dose of 3 mg three times daily, later reduced to twice daily for maintenance).

Treatment should be individualized. The course of therapy generally lasts for at least 3 years or at least 2 years after achieving biochemical remission. For patients with two or more relapses, long-term maintenance therapy with the lowest effective dose is recommended. In cases of cholestasis, or overlap syndromes such as AIH + PBC or AIH + PSC, ursodeoxycholic acid may be added. For patients unresponsive to immunosuppressive therapy, alternatives such as cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, or rituximab may be considered.

In cases of AIH with no disease activity or spontaneous remission, as well as in non-active cirrhosis, immunosuppressive therapy may not be necessary, but close long-term follow-up (e.g., every 3–6 months) is essential. For patients with mild inflammatory activity (serum aminotransferase levels <3 times ULN, IgG <1.5 times ULN) or mild interface hepatitis on pathology, the benefits and risks of immunosuppressive therapy should be carefully weighed. In such cases, immunosuppressive therapy may be deferred, and hepatoprotective anti-inflammatory agents such as glycyrrhizin preparations can be used with close monitoring. If significant clinical symptoms or pronounced inflammatory activity occur, immunosuppressive therapy should be initiated.

Prognosis

The prognosis of autoimmune hepatitis varies widely. In general, the prognosis is favorable after achieving biochemical remission, with a 10-year overall survival rate of approximately 80%–93%. Key factors influencing long-term prognosis include the presence of cirrhosis at diagnosis, the response to treatment, and the frequency of relapses following treatment.