Diarrhea is a symptom associated with numerous diseases and is characterized by an increase in stool frequency (>3 times/day), stool volume (>200 g/day) accompanied by changes in stool consistency and frequency, or loose stools with a water content exceeding 85%. Clinically, diarrhea can be categorized into acute and chronic types based on its duration. Acute diarrhea lasts less than 4 weeks, while chronic diarrhea lasts for 4 weeks or more or recurs over a prolonged period. In addition to duration, factors such as medical history, stool characteristics, pathophysiological changes, endoscopic findings, and biopsy results are important for classifying, diagnosing, and differentiating the causes of diarrhea.

Types of Diarrhea

Based on pathophysiological mechanisms, diarrhea can be classified into four types. However, in clinical practice, many cases of diarrhea are caused by a combination of mechanisms rather than a single one.

Osmotic Diarrhea

Osmotic diarrhea results from the presence of hyperosmolar substances, such as food or medication, in the intestinal lumen, leading to increased osmotic pressure and the movement of large amounts of fluid into the intestinal lumen. Clinically, it is characterized by improvement or cessation of diarrhea with fasting or discontinuation of the offending agent. Common causes include organic maldigestion, ingestion of indigestible or poorly absorbed food, food intolerances, and hyperosmolar diarrhea caused by impaired mucosal transport mechanisms.

Secretory Diarrhea

Secretory diarrhea occurs when the intestinal mucosa is stimulated to excessively secrete water and electrolytes, resulting in an imbalance between secretion and absorption. The clinical features of secretory diarrhea include:

- Stool volume exceeding 1 liter per day (and may reach up to 10 liters).

- Watery stools without pus or blood.

- Stool pH that is typically neutral or alkaline.

- Persistence of diarrhea even after 48 hours of fasting, with stool volume remaining greater than 500 mL/day.

Exudative Diarrhea

Exudative diarrhea, also known as inflammatory diarrhea, occurs when inflammation, ulcers, or other pathological changes in the intestinal mucosa compromise its integrity, leading to the exudation of large amounts of fluid into the intestinal lumen. Pathophysiological abnormalities such as malabsorption, dysmotility, and altered intestinal microecology also play important roles in inflammatory diarrhea.

This type of diarrhea can be categorized into infectious and non-infectious causes. Infectious causes are often due to pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, or fungi, while non-infectious causes include autoimmune diseases, tumors, radiation, and malnutrition, which may lead to mucosal necrosis and exudation.

Exudative diarrhea is characterized by the presence of exudates or blood in the stool. Grossly visible pus and blood in the stool are commonly associated with lesions in the left colon or entire colon. Exudation and bleeding caused by small intestinal lesions are often evenly mixed with stool, and grossly visible pus or blood is usually absent unless there is a large amount of exudation or rapid intestinal motility. Microscopic examination is often required to detect these abnormalities.

Motility-Related Diarrhea

Motility-related diarrhea is caused by excessive intestinal motility, which reduces the contact time between intestinal contents and the mucosa, impairing digestion and absorption and leading to decreased absorption of water and electrolytes. This type of diarrhea is characterized by urgency, unformed or watery stools, and the absence of exudates or blood. It is often accompanied by hyperactive bowel sounds or abdominal pain.

Causes of increased intestinal motility include:

- Physical stimuli, such as exposure to cold affecting the abdomen or intestines.

- Medications, such as mosapride or neostigmine.

- Psychological and neurological factors, such as psychological stress or abnormal increases in substances like thyroxine, serotonin, substance P, or vasoactive intestinal peptide.

- Enteric neuropathy, such as in diabetes.

- Gastrointestinal surgery, which may result in excessive food entering the distal intestine.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of chronic diarrhea aims to identify the underlying cause. Since a wide range of diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract, hepatobiliary system, pancreas, and systemic conditions can lead to diarrhea, clinical information should be collected from aspects such as age, sex, mode of onset, disease course, stool frequency and characteristics, the relationship between diarrhea and abdominal pain, associated symptoms and signs, and factors that exacerbate or relieve symptoms. These findings can help to preliminarily determine the cause of diarrhea. A definitive diagnosis is established by combining clinical history with physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies.

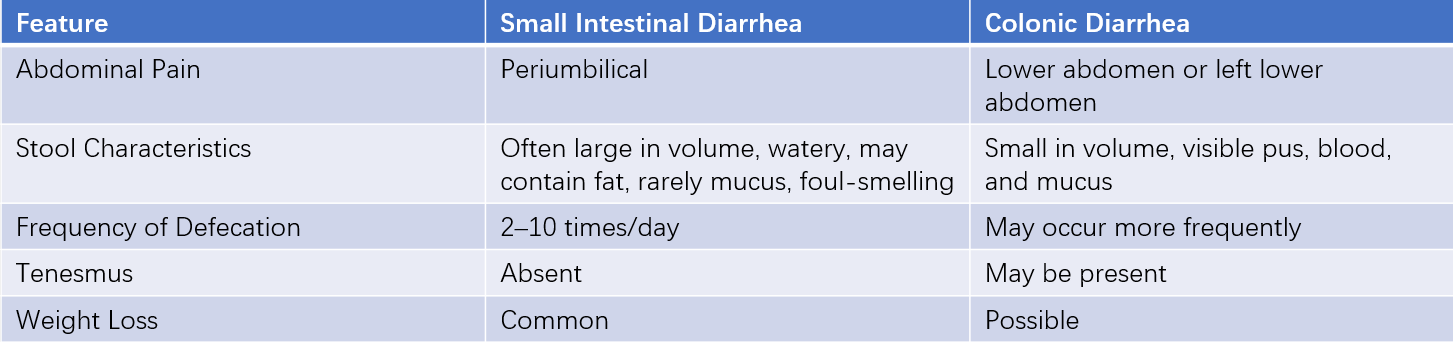

Table 1 Key points for differentiating small intestinal diarrhea and colonic diarrhea

Chronic diarrhea should be distinguished from fecal incontinence, which refers to involuntary defecation typically caused by neuromuscular disorders affecting the anorectal region or pelvic floor diseases. Auxiliary examinations are helpful in diagnosis and differentiation.

Laboratory Tests

Stool Examination

Stool tests include occult blood testing, smears for detecting white blood cells, red blood cells, undigested food particles, parasites, and eggs. Sudan III staining is used to detect fecal fat. Stool smears for bacteria and fungi, as well as stool bacterial cultures, are also included.

Blood Tests

Blood tests such as complete blood count, serum electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, and blood gas analysis are helpful in diagnosing and differentiating chronic diarrhea. Measurement of gastrointestinal hormones or peptides in the blood is valuable for diagnosing and differentiating secretory diarrhea caused by neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas.

Small Intestine Function Tests

Tests such as the D-xylose absorption test, vitamin B12 absorption test, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) detection are useful for assessing the absorptive function of the small intestine.

Imaging and Endoscopic Examinations

Imaging Studies

Ultrasound can help identify hepatobiliary and pancreatic diseases. Abdominal X-rays, barium swallow, barium enema, CT, and selective angiography are useful for evaluating the structure of the gastrointestinal wall, the intestinal lumen, blood supply, detecting gastrointestinal tumors, and assessing gastrointestinal motility. Spiral CT virtual endoscopy improves the detection rate and accuracy of intestinal lesions. PET-CT is helpful for identifying hypermetabolic lesions. Intestinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides detailed visualization of the intestinal wall and lumen. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has high diagnostic value for biliary and pancreatic duct diseases.

Endoscopy

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is crucial for diagnosing chronic diarrhea caused by tumors and inflammatory lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract and colon. Capsule endoscopy is valuable for detecting small intestinal lesions and is considered a first-line method for small intestine diseases. Push enteroscopy allows observation of the duodenum and proximal jejunum, while balloon-assisted enteroscopy enables examination of the entire small intestine. These techniques allow for small intestine biopsy and aspiration of jejunal fluid for laboratory testing and culture, aiding in the diagnosis of diseases such as celiac disease, tropical sprue, small intestinal malabsorption syndrome, certain parasitic infections, Crohn's disease, small intestinal lymphoma, and nonspecific ulcers. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is important for diagnosing and treating chronic diarrhea associated with biliary and pancreatic diseases.

Treatment

Treatment should target the underlying cause, but a significant proportion of chronic diarrhea cases require symptomatic and supportive management based on the pathophysiological characteristics of the condition.

Etiological Treatment

Infectious diarrhea requires pathogen-specific treatment. For antibiotic-associated diarrhea, discontinuation or adjustment of the offending antibiotic is necessary, and probiotics may be added. Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective treatment for Clostridioides difficile infection-associated diarrhea.

Lactose intolerance and celiac disease require the elimination of lactose or gluten from the diet, respectively.

Allergic or drug-related diarrhea necessitates avoidance of allergens and cessation of the offending medication.

Hyperosmolar diarrhea requires discontinuation of hyperosmolar medications or diets.

Diarrhea caused by bile acid malabsorption can be treated with cholestyramine to bind bile acids and reduce diarrhea.

Chronic pancreatitis may benefit from supplementation with pancreatic enzymes or other digestive enzymes.

Inflammatory bowel disease can be managed with aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents.

Gastrointestinal tumors should be treated with surgical resection or chemotherapy. Somatostatin and its analogs can be used as adjunctive therapy for carcinoid syndrome and neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas.

Symptomatic Treatment

Maintaining Water and Electrolyte Balance

Correction of water, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances caused by diarrhea is essential.

Nutritional Support Therapy

For patients with severe malnutrition, enteral or parenteral nutrition support is necessary. Glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in the body’s amino acid pool, is a non-essential amino acid but is crucial for the rapid growth of intestinal mucosal cells. It is associated with intestinal mucosal immune function and protein synthesis. For patients with diffuse intestinal mucosal damage or atrophy, glutamine is an important nutrient for mucosal repair and can be supplemented as an adjunctive therapy.

Antidiarrheal Agents

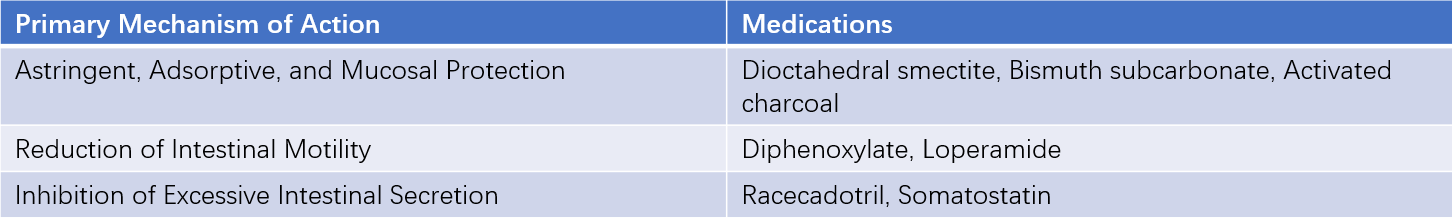

In addition to addressing the underlying cause, antidiarrheal agents listed in Table 2 may be selectively used based on the pathophysiological characteristics of the diarrhea. For infectious diarrhea, antidiarrheal agents, especially motility-inhibiting agents, should be avoided or used cautiously until the infection is effectively controlled.

Table 2 Commonly used antidiarrheal agents