Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrotic interstitial pneumonia characterized histologically and/or on chest HRCT by usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). The cause is unknown, and it predominantly occurs in older individuals.

Epidemiology

IPF is the most common type of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia in clinical practice, with an increasing incidence. In the United States, the prevalence and annual incidence of IPF are reported to be 14-42.7 per 100,000 population and 6.8-16.3 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Pathology

The hallmark pathological change of IPF is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). The histological features of UIP include dense fibrosis with a patchy distribution, predominantly affecting the subpleural or interlobular septal areas. Under low magnification, the lesions show temporal heterogeneity, with fibrotic areas adjacent to normal lung tissue. Dense fibrotic scars are accompanied by scattered fibroblastic foci.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The exact cause of IPF remains unclear. However, factors such as genetic susceptibility, aging, smoking, environmental exposure, microbial pathogens, and chronic inhalation have been identified as risk factors for IPF.

The pathogenesis of IPF is not fully understood, but it is believed to originate from abnormal repair processes following repeated micro-injuries to the alveolar epithelium. The main mechanisms include:

- Telomerase gene mutations and telomere shortening: Accelerated aging.

- Alveolar epithelial injury and abnormal activation: Reduced autophagy and production of profibrotic factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), creating a localized profibrotic microenvironment and disrupting epithelial regeneration.

- Fibroblast proliferation and activation: Transformation into myofibroblasts, leading to excessive extracellular matrix deposition, resulting in fibrotic scarring, honeycombing, lung structural destruction, and functional loss.

Other factors contributing to pulmonary fibrosis include macrophage polarization from M1 to M2, mutations in the MUC5B and TOLLIP genes, alterations in the lung microbiome, and host immune responses to microorganisms.

Clinical Manifestations

IPF typically develops after the age of 50, with an insidious onset. The primary symptoms include exertional dyspnea that progressively worsens and a persistent dry cough. Systemic symptoms are generally mild but may include discomfort, fatigue, and weight loss, while fever is rare. Approximately 75% of patients have a history of smoking. About half of the patients exhibit clubbing of the fingers, and 90% have Velcro crackles at the lung bases. In advanced stages, symptoms such as cyanosis, pulmonary hypertension, and signs of right heart failure may appear.

Auxiliary Examinations

Chest X-ray

This typically shows bilateral reticular or reticulonodular opacities in the subpleural and basal regions, with honeycombing and volume loss in the lower lobes.

Figure 1 Chest X-ray changes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

The chest X-ray shows diffuse reticular opacities in both lungs, predominantly in the subpleural and basal regions.

Chest HRCT

HRCT can reveal characteristic UIP changes. Typical UIP findings on HRCT include:

- Reticular opacities and honeycombing, with or without traction bronchiectasis.

- Predominant subpleural and basal distribution, with a diagnostic concordance rate with pathological UIP greater than 90%.

Probable UIP findings include:

- Reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis but no honeycombing.

- Predominant subpleural and basal distribution, with a diagnostic concordance rate of 70-89% with pathological UIP.

HRCT has become a critical diagnostic tool for IPF and can replace surgical lung biopsy in many cases. If the distribution and features do not align with UIP, the condition may be classified as indeterminate UIP or non-UIP, requiring biopsy for pathological diagnosis.

Figure 2 Chest HRCT changes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

The chest HRCT demonstrates patchy reticular opacities with a subpleural distribution in the peripheral zones of both lungs, accompanied by honeycombing.

Pulmonary Function Tests

Findings typically show restrictive ventilatory dysfunction and reduced diffusing capacity, accompanied by hypoxemia or type I respiratory failure. Early in the disease, resting pulmonary function may be normal or near normal, but exercise testing reveals increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (P(A-a)O2) and decreased oxygen tension.

Blood Tests

Elevated serum KL-6 levels, mild abnormalities in ESR, antinuclear antibodies, and rheumatoid factor may be observed, although these findings are nonspecific. Testing for connective tissue disease-related autoantibodies helps differentiate IPF from other conditions.

BALF/TBLC

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) analysis often shows increased neutrophils and/or eosinophils. Transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) is not diagnostic for IPF. However, with the increased use of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC), it is now considered a potential alternative to surgical lung biopsy (SLB) in experienced centers.

Surgical Lung Biopsy (SLB)

For patients with indeterminate or non-UIP patterns on HRCT, unclear diagnoses, and no surgical contraindications, SLB should be considered. The pathological hallmark of IPF is UIP, with diagnostic criteria including:

- Dense fibrosis with lung architectural destruction (e.g., destructive scarring and/or honeycombing).

- Fibrosis predominantly distributed in subpleural and/or interlobular septal areas.

- Patchy parenchymal fibrosis.

- Fibroblastic foci.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for IPF:

- Presence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) with exclusion of other possible causes (e.g., environmental exposures, drugs, and connective tissue diseases).

- HRCT findings consistent with UIP or probable UIP pattern.

- Diagnosis of UIP confirmed by a combination of HRCT and SLB/TBLC pathological findings, following multidisciplinary discussion.

Acute Exacerbation of IPF (AE-IPF)

AE-IPF is defined as acute or significant worsening of respiratory symptoms caused by new diffuse alveolar damage in patients with IPF. Diagnostic criteria include:

- Past or current diagnosis of IPF.

- Significant worsening of respiratory symptoms within one month.

- New bilateral ground-glass opacities with or without consolidation on CT, superimposed on a background of UIP.

- Exclusion of heart failure or fluid overload as the primary cause.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IPF requires the exclusion of other causes of ILD. While UIP is the gold standard for diagnosing IPF, it can also be seen in conditions such as fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, and connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTD-ILD).

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is often associated with a history of exposure to environmental antigens (e.g., pigeon breeding, mold exposure). BAL fluid analysis typically shows an increased lymphocyte proportion.

Asbestosis, Silicosis, or Other Occupational Lung Diseases

A history of exposure to asbestos, silica, or other occupational dust is key.

CTD-ILD

This is frequently associated with systemic symptoms such as rash, arthritis, and multi-organ involvement, along with positive specific autoantibodies.

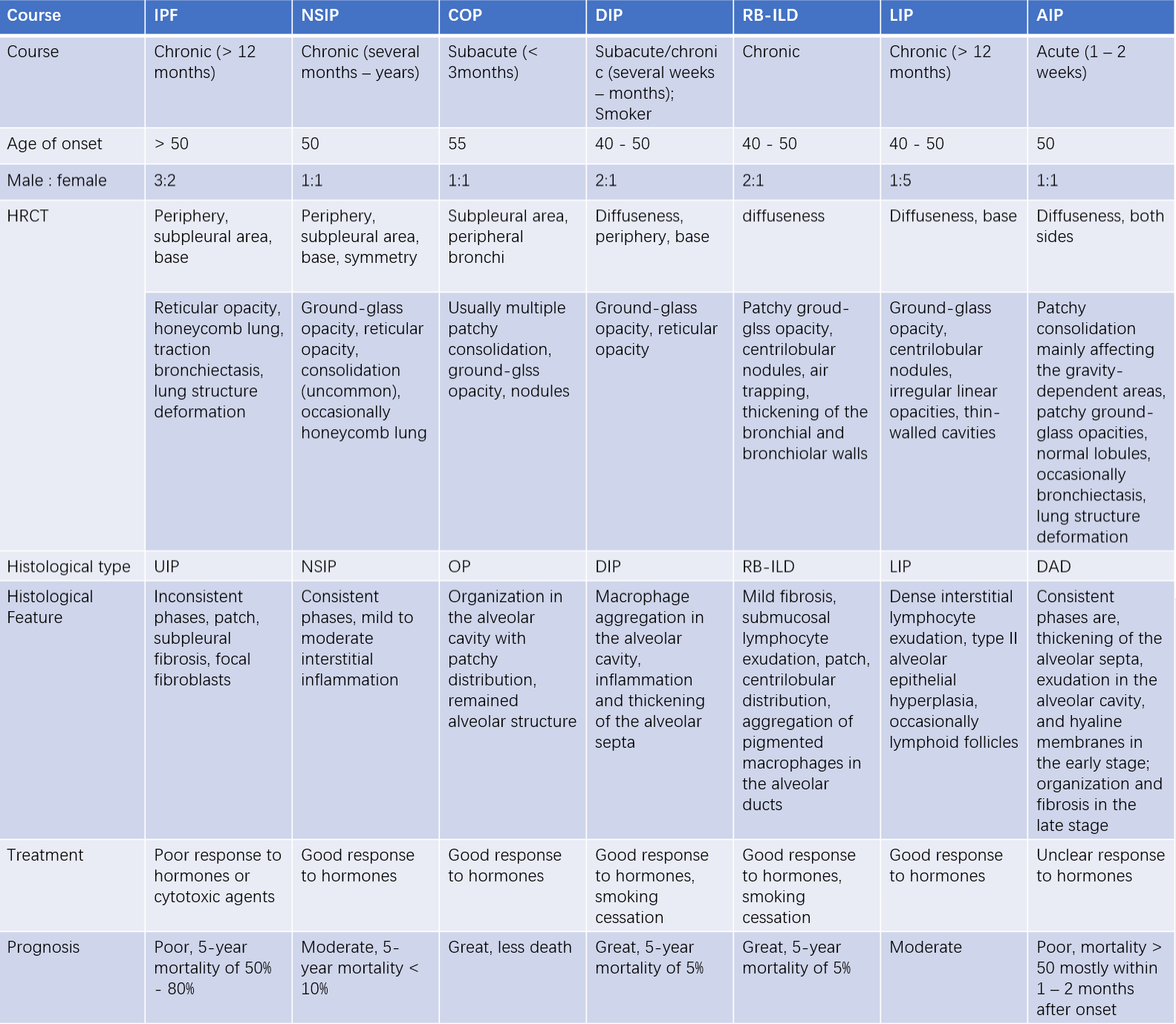

Table 1 Comparison of clinical, radiological, pathological features, and prognosis of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs)

Treatment

IPF is incurable, and treatment aims to slow disease progression, improve quality of life, and extend survival. Management includes antifibrotic drugs, nonpharmacological treatments, management of comorbidities, palliative care, disease monitoring, patient education, and self-management.

Antifibrotic Therapy

Evidence-based studies have shown that pirfenidone and nintedanib can slow the decline in lung function in IPF patients:

- Pirfenidone: A multifunctional pyridine compound with anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and antioxidant properties.

- Nintedanib: A multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR).

- N-acetylcysteine: As a mucolytic agent, high doses (1,800 mg/day) may have antioxidative and antifibrotic effects and have been shown to benefit certain patients with the TOLLIP CC genotype.

Nonpharmacological Treatment

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for IPF patients when possible.

Long-term oxygen therapy is indicated for patients with significant resting hypoxemia (PaO2 < 55 mmHg or SpO2 < 88%).

Mechanical ventilation is generally not recommended for respiratory failure caused by IPF.

Lung Transplantation

Lung transplantation offers a 5-year survival rate exceeding 50% and is currently the only effective treatment for end-stage IPF. Eligible patients should be actively considered for transplantation when possible.

Management of Comorbidities

Treatment of associated conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other comorbidities can alleviate symptoms or improve outcomes.

For pulmonary hypertension associated with IPF, medications such as sildenafil or inhaled prostacyclins may be considered.

Symptomatic Treatment

This focuses on alleviating symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and anxiety to improve the patient’s quality of life.

Treatment of Acute Exacerbation of IPF (AE-IPF)

Given the severity and high mortality rate of AE-IPF, high-dose corticosteroids are recommended in clinical practice despite the lack of randomized controlled trials.

Supportive measures include oxygen therapy, treatment of underlying lung infections, and symptomatic management.

Mechanical ventilation is generally not recommended for respiratory failure caused by IPF, but noninvasive ventilation may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Patient Education and Self-management

Smoking cessation is strongly advised. Vaccination against influenza and pneumonia is recommended.

Natural Course and Prognosis

The median survival time following an IPF diagnosis is 2-3 years, although the disease course and outcomes vary widely among individuals.

Most patients experience a slow, predictable decline in lung function. A minority of patients experience recurrent acute exacerbations. Rarely, some patients may develop rapidly progressive disease.

Prognostic factors include severity of dyspnea, lung function decline, and extent of fibrosis and honeycombing on HRCT, and results of the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), especially dynamic changes in these parameters.

Reliable predictors of mortality include:

- Baseline DLCO < 40% of predicted.

- SpO2 < 88% during the 6MWT.

- Absolute decline in FVC > 10% or DLCO > 15% within 6-12 months.