Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that affects multiple systems, primarily involving the lungs and lymphatic system, followed by the eyes and skin.

Epidemiology

Due to the asymptomatic nature of some cases and the possibility of spontaneous resolution, precise epidemiological data are lacking. Sarcoidosis primarily affects young and middle-aged adults (<40 years), with a slightly higher incidence in females than in males. Reported prevalence ranges from less than 1/100,000 to over 40/100,000, with the highest rates observed in Scandinavian and African-American populations. It is more common in colder regions than tropical areas and more frequent in Black individuals compared to White individuals, showing significant geographic and racial differences.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Although the exact cause and pathogenesis of sarcoidosis remain unclear and require further research, it is currently believed that sarcoidosis arises from an exaggerated Th1/Th17 immune response in genetically predisposed individuals exposed to specific environmental triggers, leading to granuloma formation in affected organs.

Pathology

The hallmark pathological feature of sarcoidosis is non-caseating epithelioid granulomas, which are primarily composed of highly differentiated mononuclear phagocytes (epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells) and lymphocytes. Giant cells may contain inclusions such as Schaumann bodies and asteroid bodies. The granuloma's center is predominantly composed of CD4+ lymphocytes, while the periphery contains CD8+ lymphocytes. Sarcoid granulomas may either resolve or progress to fibrosis.

In the lungs, 75% of granulomas are distributed along the lymphatic pathways, located near or within the bronchovascular bundles, subpleural regions, or interlobular septa. Open lung biopsy or autopsy reveals vascular involvement in more than half of cases. Additionally, airway involvement is common, affecting the airways internally or externally.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is highly variable, depending on the disease's acute or chronic onset, the organs involved, the activity of the granulomas, and racial and regional differences.

Acute Sarcoidosis

Acute sarcoidosis (Löfgren syndrome) presents with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, arthritis, and erythema nodosum, often accompanied by fever, myalgia, and general malaise. Spontaneous remission occurs in 85% of patients within one year.

Subacute/Chronic Sarcoidosis

Approximately 50% of sarcoidosis cases are asymptomatic and are incidentally discovered during routine physical examinations or chest imaging.

Systemic Symptoms

About 1/3 of patients exhibit nonspecific symptoms such as fever, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, and diaphoresis.

Intrathoracic Sarcoidosis

Over 90% of cases involve the lungs. Clinical manifestations are often insidious, with 30-50% of patients experiencing cough, chest pain, or dyspnea. About 20% exhibit airway hyperreactivity, sometimes with wheezing.

Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis

This includes involvement of lymph nodes, skin, eyes, heart, endocrine organs, and other systems.

Auxiliary Examinations

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray

Over 90% of patients show abnormalities on chest X-rays, making it a sensitive tool for initial diagnosis. The most common finding is bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL), with or without right paratracheal lymphadenopathy. Disease staging based on posteroanterior chest X-rays correlates with the likelihood of spontaneous remission.

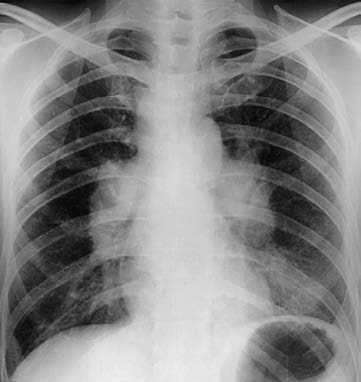

Figure 1 Chest X-ray findings of stage I sarcoidosis

A 36-year-old patient was found to have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on a routine chest X-ray examination, leading to the diagnosis of stage I sarcoidosis.

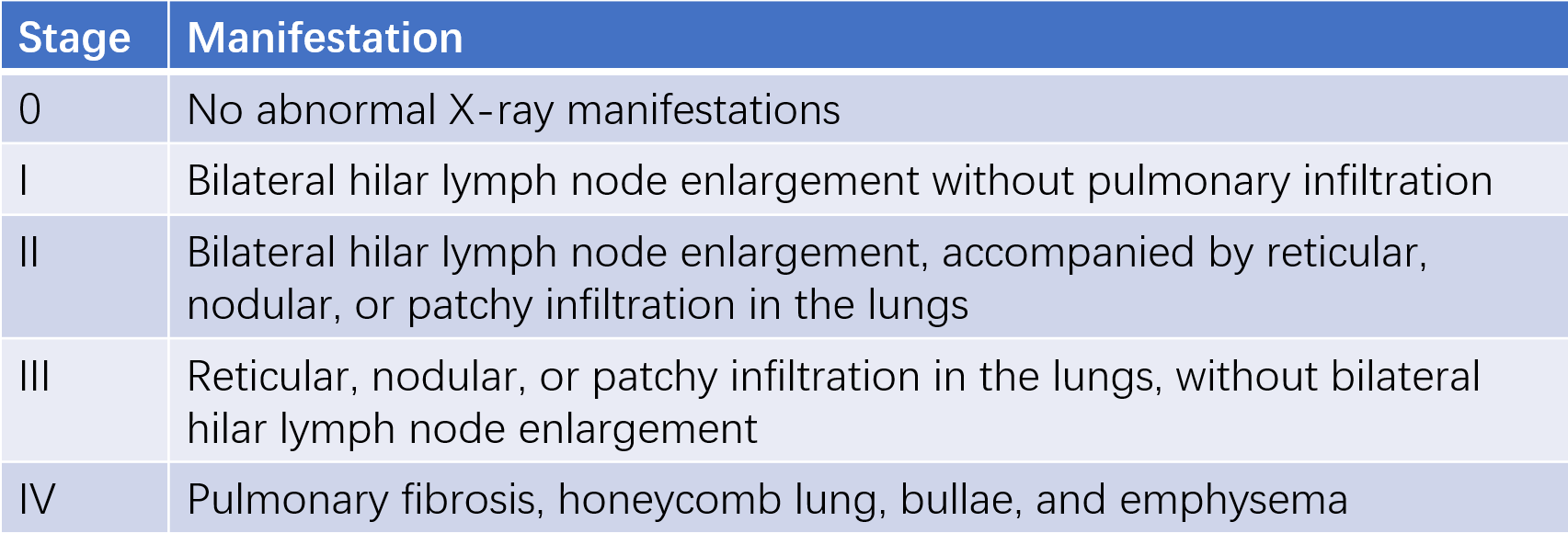

Table 1 Chest X-ray staging of sarcoidosis

Chest CT/HRCT

Typical HRCT findings include small nodules distributed along the bronchovascular bundles and interlobular septa, which may coalesce. Other abnormalities include ground-glass opacities, linear bands, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and distortion or deformation of blood vessels or bronchi. Lesions predominantly affect the upper lobes, with relatively spared lung bases. Enlarged lymph nodes may be seen in the pretracheal, paratracheal, para-aortic, and subcarinal regions.

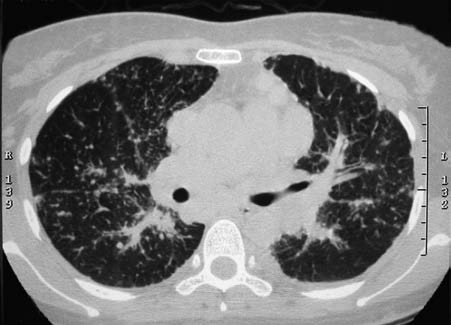

Figure 2 HRCT findings in sarcoidosis

The HRCT scan shows numerous small nodules distributed along the lymphatic pathways, located in the peribronchovascular interstitium, interlobular septa, and subpleural regions. Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is also observed.

Radionuclide Imaging

Granulomas with active macrophages exhibit increased uptake of 67Ga, and granulomatous lesions may be detected using 67Ga scintigraphy, showing characteristic panda sign (involvement of nasal mucosa, bilateral lacrimal glands, and parotid glands) or lambda (λ) sign (uptake in right paratracheal and bilateral hilar lymph nodes). However, this lacks diagnostic specificity. 18F-FDG PET can also aid in diagnosing sarcoidosis, identifying more subtle lesions and assessing cardiac involvement. However, it cannot distinguish between malignancy, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis, requiring correlation with other findings.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

Over 80% of patients with stage I sarcoidosis have normal lung function. In stages II and III, 40-70% show abnormalities, with restrictive ventilatory defects, reduced diffusing capacity, and oxygenation impairment being characteristic. More than 1/3 of patients exhibit concurrent airflow limitation.

Bronchoscopy and Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

Bronchoscopy may reveal widened carina due to subcarinal lymphadenopathy or mucosal nodules caused by airway involvement. BAL fluid typically shows an increased proportion of lymphocytes and an elevated CD4/CD8 ratio (>3.5).

Diagnosis can often be achieved via transbronchial biopsy (TBB), transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), or EBUS-TBNA (endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration), which are highly diagnostic and minimally invasive, making them crucial tools for confirming pulmonary sarcoidosis. Mediastinoscopy or surgical lung biopsy is generally unnecessary.

Blood Tests

Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), produced by epithelioid cells in sarcoid granulomas, reflects granuloma burden and may help assess disease activity. However, it lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity for diagnostic purposes.

Other markers of disease activity include elevated serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and hypercalcemia.

Tuberculin Skin Test (TST)

A weak or absent reaction to tuberculin skin testing (PPD 5TU) is characteristic of sarcoidosis and can help differentiate it from tuberculosis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires meeting the following three criteria:

- Clinical and chest imaging findings consistent with sarcoidosis.

- Biopsy confirmation of non-caseating epithelioid granulomas.

- Exclusion of other potential causes.

After the diagnosis is established, it is necessary to assess the extent of organ involvement, stage the disease (as described above), and evaluate its activity. There are no strict standards for determining disease activity. Acute onset, prominent clinical symptoms, rapid disease progression, involvement of critical organs, and elevated serum ACE levels suggest active disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Hilar Lymph Node Tuberculosis

Patients are typically younger, and tuberculin skin tests are often positive. Hilar lymphadenopathy is usually unilateral and sometimes accompanied by calcification or a primary pulmonary lesion. CT may reveal necrosis in the center of the lymph nodes.

Lymphoma

Associated symptoms often include fever, weight loss, and anemia. Mediastinal lymph nodes, such as those in the superior mediastinum or subcarinal region, are commonly involved, often showing unilateral or asymmetric bilateral enlargement with lymph node fusion. Diagnosis can be confirmed through additional tests and biopsy.

Metastatic Tumors in the Hilum

Lung cancer or extrapulmonary tumors metastasizing to hilar lymph nodes often present with corresponding symptoms and signs. Further investigation of suspected primary lesions can help differentiate.

Other Granulomatous Diseases

Diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, beryllium disease, silicosis, or granulomas caused by infectious or chemical factors should be differentiated from sarcoidosis through clinical evaluation and comprehensive analysis of relevant tests.

Treatment

Approximately half of sarcoidosis cases are asymptomatic, and 60-70% of cases resolve spontaneously. Only 10-30% of cases follow a chronic course. Therefore, asymptomatic and inactive sarcoidosis generally does not require treatment but should be monitored.

Treatment is indicated for sarcoidosis with significant symptoms, marked pulmonary function abnormalities, parenchymal lung involvement, or extrapulmonary manifestations—especially when critical organs such as the heart, nervous system, liver, or spleen are involved.

The standard treatment is systemic corticosteroids. For pulmonary sarcoidosis, the initial dose is typically prednisone (or an equivalent corticosteroid) at 0.5 mg/kg/day or 20-40 mg/day, gradually tapering the dose in 2-4 weeks to a maintenance dose of 5-10 mg/day. The total treatment duration is 6-24 months.

The recurrence rate of sarcoidosis is 16-74%. For patients prone to relapse, the corticosteroid dose should be appropriately increased.

If corticosteroids are not tolerated or ineffective, other immunosuppressive agents can be considered, including methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate mofetil, or biologics such as infliximab or adalimumab.

After completing treatment, follow-up is required every 3-6 months for at least 3 years or until the disease stabilizes.

Prognosis

The course and prognosis of sarcoidosis vary widely:

- The spontaneous remission rate for stage I pulmonary sarcoidosis is 55-90%.

- For stage II pulmonary sarcoidosis, the spontaneous remission rate is 40-70%.

- For stage III pulmonary sarcoidosis, the rate drops to 10-20%.

Patients with acute onset often have a good prognosis, either with treatment or spontaneous remission. However, those with chronic progressive disease, multi-organ dysfunction, or extensive pulmonary fibrosis generally have a poorer prognosis. The overall mortality rate is 1-5%, with most deaths resulting from respiratory failure or involvement of the heart or central nervous system.

Approximately 75% of deaths are due to progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis. However, reliable prognostic indicators for severe chronic progressive sarcoidosis have yet to be identified.