Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a slow-progressing neoplastic disorder of mature B lymphocytes characterized by the accumulation of clonal B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen, and lymphatic tissues such as lymph nodes. While morphologically resembling mature lymphocytes, CLL cells display abnormal immunophenotypes and functions. All CLL cases originate from mature B cells, though the etiology and pathogenesis remain incompletely understood.

Clinical Manifestations

This disease predominantly affects the elderly population and is more frequently observed in males. The onset is insidious, with the majority of patients showing no apparent symptoms at diagnosis. Over half the cases are incidentally identified during routine health examinations or during consultation for unrelated conditions. In symptomatic cases, early manifestations may include fatigue, lethargy, weight loss, low-grade fever, and diaphoresis.

Approximately 60%–80% of patients exhibit lymphadenopathy, most commonly in the head and neck, supraclavicular, axillary, or inguinal regions. The enlarged lymph nodes are usually painless, firm, and nonadherent, and may progressively enlarge or coalesce as the disease advances. CT imaging may reveal mediastinal, retroperitoneal, or mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Enlarged lymph nodes can compress structures such as the trachea, superior vena cava, bile ducts, or ureters, leading to corresponding symptoms.

More than half of the patients present with mild to moderate splenomegaly, while hepatomegaly is typically mild and sternal tenderness is rare. In advanced stages, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia may develop, often accompanied by infections. Immune dysfunction is common, with approximately 10%–15% of patients developing autoimmune complications, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) or immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Some cases may transform into Richter syndrome, which involves progression to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or other aggressive lymphomas, including Hodgkin lymphoma.

Laboratory Investigations

Complete Blood Count

Persistent lymphocytosis serves as a hallmark, with monoclonal B lymphocytes in peripheral blood often exceeding an absolute count of ≥5×109/L. Most leukemic cells resemble mature small lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm and clumped chromatin in the nucleus. Peripheral blood smears often show smudge cells or broken cells. A minority of patients present with abnormal cell morphology characterized by larger, immature cells, sometimes with deep nuclear indentations (Reider cells). Rarely, blast cells may be observed. The proportion of neutrophils tends to decrease. As the disease progresses, anemia and thrombocytopenia may develop.

Bone Marrow Examination

Bone marrow reveals hyperplasia or marked hyperplasia, with lymphocytes representing ≥40%, predominantly mature lymphocytes. Erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocyte lineages show suppressed proliferation, and advanced stages may show a significant decline in these cell populations. In cases accompanied by hemolysis, compensatory erythroid hyperplasia is observed.

Immunophenotyping

Immunological testing represents a critical tool for CLL diagnosis and monitoring response to therapy, often conducted using flow cytometry. CLL cells display monoclonality and exhibit typical B-cell immunophenotypic characteristics. Surface immunoglobulin (SmIg) expression is weak, typically of the IgM or IgM/IgD subtype, with κ or λ light chain restriction. Cells express CD5, CD19, CD23, and strongly express CD200. Weak expression is observed for CD20, CD22, and CD11c, while FMC7 and CD79b are negative or weakly positive. CD10 and Cyclin D1 are negative. The RMH immunophenotypic scoring system can provide differentiation, with CLL typically scoring 4–5, while other B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders score 0–2. When RMH scores are ≤3, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended to exclude mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), with CD200 and CD43 expression patterns providing additional context. Moreover, LEF1 positivity in CLL and negativity in MCL may help with differential diagnosis.

Cytogenetic Analysis

The low mitotic activity of CLL cells results in lower detection rates for chromosomal abnormalities. However, interphase FISH can identify chromosomal abnormalities in over 80% of patients. Common abnormalities include 13q14 deletions (50%), trisomy 12 (20%), 11q22-23 deletions, 17p13 deletions, and 6q deletions. Among patients treated with immunotherapy or chemotherapy, isolated 13q14 deletions indicate a favorable prognosis, whereas trisomy 12 and a normal karyotype are associated with an intermediate prognosis. Deletions in 17p13 or 11q22-23 correspond to poor outcomes.

Molecular Testing

Approximately 50%–60% of CLL cases exhibit somatic hypermutation in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) gene. Patients with mutated IGHV have longer survival, whereas those with unmutated IGHV exhibit poorer outcomes. TP53 gene mutations, present in 5%–8% of newly diagnosed CLL patients, are linked to disease progression, therapy resistance, and shorter survival (TP53 is located on 17p13). Recent discoveries of mutations in genes such as SF3B1, NOTCH1, and MYD88 in CLL suggest potential associations with disease pathogenesis and treatment resistance.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are as follows:

The absolute count of peripheral blood monoclonal B lymphocytes (CD19+ cells) being ≥5×109/L and persisting for ≥3 months is a defining feature (the length of time is less critical for diagnosis if typical CLL immunophenotype and morphological characteristics are present). If the B lymphocyte count is <5×109/L but cytopenias caused by bone marrow infiltration by CLL cells are present, a diagnosis of CLL can still be established.

A key hallmark in peripheral blood smears is a marked increase in small, morphologically mature lymphocytes. Atypical lymphocytes and prolymphocytes account for no more than 55% of the circulating lymphocytes.

A characteristic immunophenotype is observed, including positivity for CD5, CD19, CD23, CD200, and CD43, as well as negativity for CD10, FMC7, and Cyclin D1. Weak expression of surface immunoglobulin (SmIg), CD20, and CD79b is also noted.

Differential diagnosis is necessary for CLL and the following conditions:

- Reactive Lymphocytosis Due to Viral Infections: Lymphocytosis in this condition is polyclonal and temporary, and lymphocyte counts typically normalize as the infection resolves.

- Other B-Cell Chronic Lymphoproliferative Disorders: Other B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative diseases involving bone marrow infiltration (e.g., follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, splenic marginal zone lymphoma) may be confused with CLL. These disorders differ from CLL in terms of disease history, cellular morphology, lymph node and bone marrow pathology, immunophenotypic patterns, and cytogenetic features.

- Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL): This condition is often characterized by pancytopenia and splenomegaly, with lymphadenopathy being rare, making differentiation relatively straightforward. However, a minority of cases exhibit elevated white blood cell counts (10–30×109/L). Peripheral blood and bone marrow findings typically include "hairy cells," which are lymphocytes with cytoplasmic projections. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) stain positivity is a hallmark. Immunophenotyping reveals CD5 negativity and strong expression of CD25, CD11c, CD103, and CD123. The characteristic BRAF V600E mutation is also diagnostic.

Clinical Staging

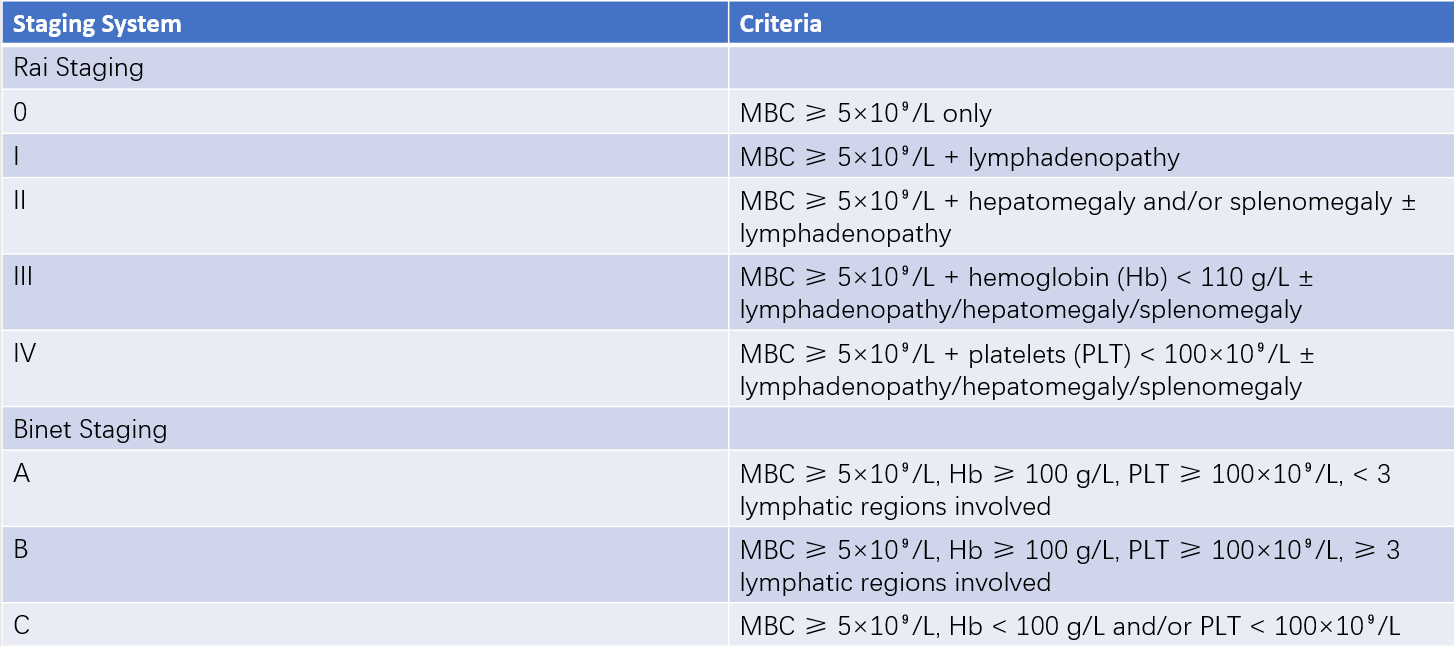

The purpose of disease staging is to guide treatment decisions and assess prognosis. Commonly used staging systems include the Rai and Binet classifications. The CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) is recommended for comprehensive prognostic evaluation.

Table 1 Rai and Binet Staging

Note: Lymphatic regions include cervical, axillary, inguinal (counted as one region for unilateral or bilateral involvement), liver, and spleen. MBC refers to the absolute count of monoclonal B-lymphocytes. Immune cytopenia is not considered part of the staging criteria.

Treatment

CLL is classified as an indolent leukemia, and immediate treatment is not necessary for all patients upon diagnosis. Retrospective studies suggest that early treatment initiation does not improve survival rates. Current guidelines indicate that early-stage patients (Rai stage 0–II or Binet stage A) often do not require therapy and should be managed with regular monitoring and follow-up. Therapy is recommended if one or more of the following criteria indicate disease activity:

- Disease-related symptoms, including unexplained weight loss ≥10% within six months, profound fatigue, non-infectious fever (exceeding 38°C) lasting ≥2 weeks, or diaphoresis.

- Splenomegaly (splenic extension >6 cm below the costal margin) or progressive/symptomatic splenomegaly.

- Progressive lymphadenopathy or lymph nodes with a maximum diameter >10 cm.

- Rapidly progressive peripheral blood lymphocytosis, defined as an increase >50% within two months, or a lymphocyte doubling time of <6 months (lymphocyte doubling time alone may not be used as an indication for therapy if the initial lymphocyte count is <30×109/L).

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and/or immune thrombocytopenia that fails to respond to corticosteroids.

- Progressive bone marrow failure, characterized by worsening anemia and/or thrombocytopenia.

- Symptomatic organ dysfunction caused by CLL, such as involvement of the skin, kidneys, lungs, or spinal cord.

Historically, CLL therapy was largely palliative, focusing on reducing tumor burden and alleviating symptoms. With the advent of novel agents, treatment outcomes have significantly improved. Achieving complete remission (CR) after therapy has been associated with improved survival compared to partial responders or nonresponders.

Molecular Targeted Therapy

Abnormal activation of multiple signaling pathways, including BTK, PI3K, and Syk, exists in CLL cells. Specific inhibitors targeting these signaling pathways have potential as therapeutic agents for CLL. Currently, BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib, zanubrutinib, orelabrutinib, and acalabrutinib are recommended as first-line treatments for CLL. The BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax is also widely used in the first-line and salvage treatment of CLL, particularly for patients with poor genetic features such as TP53 mutations or 17p deletions.

Chemotherapy

Alkylating Agents

Chlorambucil (CLB) achieves a response rate of 50%–60% as monotherapy for previously untreated CLL; however, the complete remission (CR) rate is below 10%. It is mainly used for older patients, those unable to tolerate other chemotherapeutic agents, or those with complications. Cyclophosphamide has similar efficacy to CLB, but the combination of cyclophosphamide with other agents in COP or CHOP regimens does not significantly surpass monotherapy. Bendamustine, a novel alkylating agent with both alkylating and antimetabolic properties, has demonstrated high response and CR rates in both untreated and relapsed/refractory CLL patients.

Purine Analogues

Fludarabine (Flu) achieves an overall response rate of 60%–80%, with CR rates of 20%–30%. The median duration of remission is approximately twice that of CLB, although no survival advantage has been observed. Patients resistant to alkylating agents may still respond to Flu. Combining purine analogues with alkylating agents, such as in the fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (FC) regimen, offers superior efficacy compared to Flu monotherapy, prolonging progression-free survival in newly diagnosed patients and providing benefits for those with relapsed or refractory CLL.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are primarily used in the treatment of autoimmune cytopenias associated with CLL. Corticosteroids are not typically used as monotherapy; however, high-dose methylprednisolone has shown substantial efficacy in cases of refractory CLL, particularly in patients with 17p deletions.

Immunotherapy

Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is effective against CD20-expressing CLL cells but is limited by low CD20 expression on CLL cell surfaces and the presence of soluble CD20 molecules in the plasma, which cause rapid clearance of rituximab in CLL patients. Higher doses or increased dosing frequency are required to achieve efficacy. Obinutuzumab, a novel humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has shown improved efficacy compared to rituximab and is also used as a first-line treatment for CLL. The combination of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapeutic agents can create a synergistic antitumor effect, enhancing overall response rates and survival outcomes.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Most CLL patients do not require hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) as a first-line treatment. However, HSCT may serve as a second-line option for high-risk or relapsed/refractory cases. Allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT) has the potential to provide long-term survival and even a cure for some patients.

Management of Complications

Due to hypogammaglobulinemia, neutropenia, and advanced age, CLL patients are highly susceptible to infections, which may lead to mortality. Aggressive infection treatment and prevention are crucial. Patients with recurrent infections or severe hypogammaglobulinemia may benefit from intravenous immunoglobulin infusions. For those with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) or immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), corticosteroids are utilized. In cases of significant lymphadenopathy, massive splenomegaly, or severe local compression symptoms where chemotherapy is ineffective, radiotherapy may be considered for symptomatic relief.

Prognosis

CLL represents a highly heterogeneous disease. Clinical courses vary from lifelong absence of treatment to rapid progression over a short period. The majority of CLL-related deaths result from severe infections, anemia, or bleeding due to bone marrow failure. Disease transformations such as Richter syndrome may occur during the disease course.

Significant advances in CLL treatment have occurred in recent years. The use of chemoimmunotherapy, combining monoclonal antibodies with chemotherapeutic agents, has significantly improved response rates and survival outcomes. Emerging therapies, including specific inhibitors targeting B-cell signaling pathways and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy, hold promise for further enhancing clinical outcomes.