Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) refers to a group of lymphomas with diverse histopathological characteristics and biological behaviors, which tend to exhibit early distant dissemination. The WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms defines each type of lymphoma as a distinct disease. The latest edition released in 2016 introduced new pathological subtypes, renamed certain categories, and included classifications based on cellular origin. For instance, "high-grade B-cell lymphoma" was added, comprising two categories:

- High-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: This subtype replaces the concept of "B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BCLU)" from the 2008 edition. It is characterized by the absence of MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 rearrangements.

- High-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 rearrangements: Commonly referred to as "double-hit lymphoma" (DHL). Cases of BCLU with such rearrangements also fall into this category.

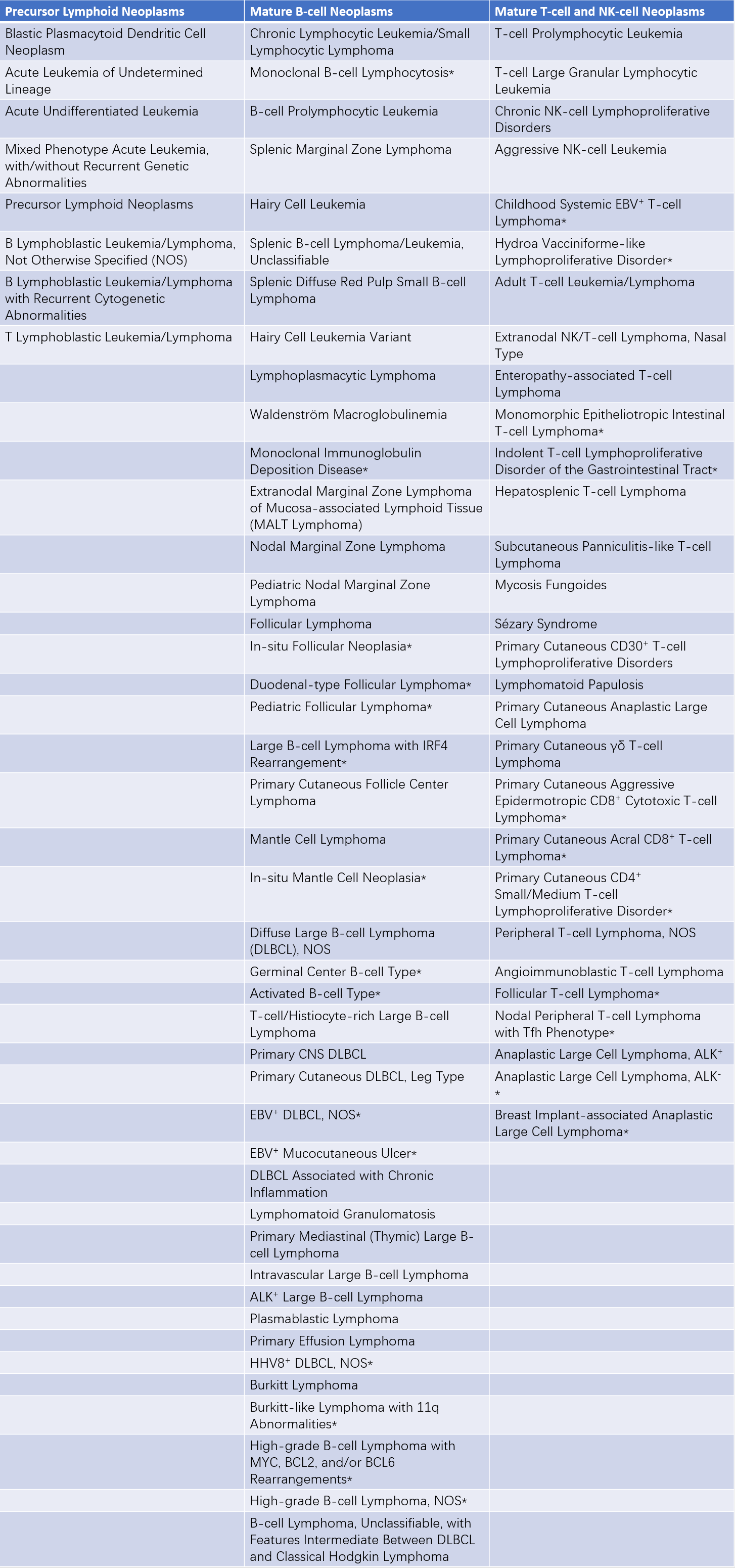

Table 1 WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (2016 Edition)

Note: Asterisks () indicate changes relative to the 2008 WHO Classification. NOS refers to "Not Otherwise Specified."

The following describes some of the most common NHL subtypes encountered in clinical practice.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most prevalent NHL subtype, accounting for approximately 35% to 40% of adult NHL cases. It is an aggressive and heterogeneous B-cell lymphoma, most frequently affecting middle-aged and elderly individuals. The typical presentation includes progressive lymphadenopathy. Pathologically, normal lymph node architecture is replaced by diffuse infiltration of large lymphoid cells. Over half of patients are at an advanced stage at diagnosis. A small proportion of cases progress or transform from indolent lymphomas. The 2016 WHO classification further divides DLBCL into germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) subtypes based on cellular origin.

DLBCL is highly responsive to immunochemotherapy. The R-CHOP regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) is the current standard of care. More than 70% of patients achieve disease remission, but only 50% to 60% achieve long-term disease-free survival. High-dose chemotherapy combined with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can provide a curative option for patients with relapsed DLBCL after first-line therapy. The emergence of targeted therapies and cellular therapies in recent years offers the potential for improving patient outcomes.

Follicular Lymphoma (FL)

Follicular lymphoma is a germinal center B-cell-derived lymphoma characterized by CD10+, BCL6+, and BCL2+ immunophenotypes, with the t(14;18) translocation. This subtype is more commonly observed in the elderly and often involves the spleen and bone marrow. It is classified as an "indolent lymphoma," demonstrating a good response to chemotherapy but remaining incurable. The disease typically runs a prolonged course with multiple relapses or transformation to an aggressive lymphoma.

Marginal Zone Lymphoma (MZL)

Marginal zone lymphoma arises from the structure between the lymphoid follicle and its marginal zone and is of B-cell origin. It belongs to the category of "indolent lymphomas." Depending on the sites of involvement, three subtypes are recognized:

- Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT): This subtype originates in extranodal marginal zones of lymphoid tissue and may feature t(11;18). It can be further divided into gastric MALT and non-gastric MALT lymphomas.

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: Clinical manifestations include anemia, splenomegaly, and lymphocytosis, with or without villous lymphocytes.

- Nodal marginal zone lymphoma: Occurs in lymph node marginal zones.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL)

Mantle cell lymphoma arises from CD5+ B-cells in the mantle zone and is marked by t(11;14)(q13;q32) chromosomal translocation, leading to overexpression of nuclear cyclin D1. This subtype predominantly affects older males and accounts for 6% to 8% of NHL cases. It is an aggressive lymphoma with rapid progression and a median survival of only 2 to 3 years. The complete response rate to chemotherapy is relatively low.

Burkitt Lymphoma (BL)

Burkitt lymphoma consists of monomorphic medium-sized cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles and round nucleoli. Its cell size falls between that of large and small lymphocytes. When it involves the bloodstream or bone marrow, it is classified as ALL L3 type. It is characterized by CD20+, CD22+, CD5-, and the presence of the t(8;14) translocation involving MYC gene rearrangements, which are critical diagnostic markers. Burkitt lymphoma exhibits extremely rapid growth and is a highly aggressive NHL subtype. It is common in children in endemic regions, where it frequently involves the jaw. In non-endemic regions, the disease mainly affects the terminal ileum and abdominal organs.

The 2016 WHO classification introduced "Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberrations" as a new variant. Almost all cases of classic Burkitt lymphoma exhibit MYC rearrangements, but this variant lacks MYC rearrangements and instead features 11q abnormalities with PAFAH1B2 overexpression. This variant primarily occurs in children and young adults and often presents with nodal disease. Its morphology and immunophenotype are similar to those of classic Burkitt lymphoma.

Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma (AITL)

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is an aggressive T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 2% of NHL cases. It is more commonly observed in elderly individuals and is characterized by symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, a positive Coombs test, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The prognosis is poor, with limited improvements achieved through conventional chemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is an aggressive T-cell-derived subtype of NHL, accounting for 2% to 7% of all NHL cases. It typically progresses rapidly. The tumor cells exhibit variable morphology and may resemble Reed-Sternberg cells, sometimes leading to confusion with Hodgkin lymphoma. These cells are typically CD30+ and are often associated with t(2;5) chromosomal abnormalities and ALK gene positivity.

Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified (PTCL-NOS)

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, refers to a diverse group of malignancies arising from mature (post-thymic) T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells.

Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome (MF/SS)

Mycosis fungoides, with peripheral blood involvement termed Sézary syndrome, is most commonly encountered as mycosis fungoides. These conditions are classified as indolent lymphoma subtypes. The neoplastic cells are mature helper T-cells, which typically express CD3+, CD4+, and CD8-.

Clinical Features

The most common clinical presentation shared by lymphomas, including NHL, is painless and progressive lymphadenopathy or localized masses. NHL exhibits distinct characteristics, as follows:

- Widespread nature: Lymph nodes and lymphoid tissue are distributed throughout the body and communicate with the mononuclear phagocyte system and hematopoietic system, enabling lymphomas to appear in virtually any region. The most commonly affected sites include lymph nodes, tonsils, spleen, and bone marrow, though extranodal organs such as the lungs, liver, and gastrointestinal tract may also be involved. Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss are often present.

- Variability: Depending on the tissues or organs involved, as well as the extent and severity of compression or infiltration, clinical symptoms exhibit significant diversity.

- Age and gender distribution: Incidence increases with age and is more common in males compared to females. Apart from indolent lymphomas, most cases progress rapidly.

- Compression and infiltration: NHL tends to exhibit compression of and infiltration into various organs to a greater extent than Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). High fever or symptoms associated with affected organs or systems are often prominent clinical features.

- Head and Neck: Lymphoid involvement in the pharyngeal region may result in dysphagia, nasal congestion, epistaxis, and submandibular lymphadenopathy.

- Thoracic Cavity: The mediastinum and pulmonary hilum are the most commonly affected regions, with half of the cases showing pulmonary infiltration or pleural effusion. Symptoms may include cough, chest tightness, dyspnea, atelectasis, and superior vena cava syndrome.

- Gastrointestinal Tract: The ileum is the most frequently involved site, followed by the stomach. Symptoms can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, or abdominal masses. Diagnosis may be confirmed during surgery for intestinal obstruction or massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

- Liver: Hepatomegaly and jaundice are typically observed in advanced stages.

- Spleen: Primary splenic NHL is relatively rare.

- Retroperitoneum: Enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes may compress the ureters, leading to hydronephrosis.

- Renal Involvement: Manifestations include renal enlargement, hypertension, renal insufficiency, and nephrotic syndrome.

- Central Nervous System (CNS): CNS involvement usually affects the meninges and spinal cord. Extradural masses may cause spinal cord compression.

- Bones: The thoracic and lumbar spine are the most commonly affected sites, presenting with bone pain, destruction of vertebrae, and symptoms of spinal cord compression.

- Skin: Cutaneous involvement may appear as masses, subcutaneous nodules, infiltrative plaques, or ulcers.

In approximately 20% of NHL cases, especially in the late stages, bone marrow involvement may occur, potentially progressing to lymphomatous leukemia.

Laboratory and Specialized Examinations

Blood and Bone Marrow Examination

In non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), white blood cell counts are often normal but may show absolute or relative lymphocytosis. Lymphoma cells can sometimes be identified in bone marrow smears in certain patients. In advanced stages, if lymphomatous leukemia develops, a leukemic blood profile or bone marrow pattern may be observed.

Serological Examination

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and increased serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels during active disease phases suggest poor prognosis. Increased serum alkaline phosphatase activity or hypercalcemia may indicate bone involvement. B-cell NHL may be complicated by hemolytic anemia, which can be Coombs test-positive or -negative. A small number of cases may also present with monoclonal gammopathy (characterized by elevated monoclonal immunoglobulins in the blood). Involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) may lead to elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein levels, with abnormal lymphoma cells detected by flow cytometry of the CSF.

Imaging Examinations

Essential imaging modalities for diagnosing lymphoma include ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and PET-CT.

Examination of Superficial Lymph Nodes

Ultrasound and radionuclide imaging can detect lesions that may go unnoticed during physical examination.

Examination of the Mediastinum and Lungs

Chest X-rays may reveal mediastinal widening, enlarged pulmonary hila, pleural effusion, or pulmonary lesions. Chest CT provides definitive identification of mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy.

Abdominal and Pelvic Lymph Node Examination

Abdominal CT is the preferred diagnostic tool. If CT results are negative but clinical suspicion remains high for lymphadenopathy, lower-extremity lymphography may be considered. While ultrasound is less accurate than CT, has poor reproducibility, and is significantly affected by intestinal gas interference, it remains a viable alternative in the absence of CT availability.

Examination of the Liver and Spleen

CT, ultrasound, radionuclide imaging, and MRI can identify single or multiple nodules but may fail to detect diffuse infiltration or miliary lesions. It is generally accepted that hepatic or splenic involvement can be confirmed when at least two imaging modalities indicate focal lesions.

Positron Emission Tomography–Computed Tomography (PET-CT)

PET-CT is capable of identifying the location and extent of lymphoma lesions. It serves as a valuable diagnostic tool for tumor characterization and localization based on biochemical imaging. PET-CT has become an important parameter for clinical staging and evaluating the therapeutic response in lymphoma patients.

Pathological Examination

Adequate-sized lymph nodes should be excised intact to avoid compression artifacts. Impression smears are prepared from the cut surface, followed by fixation of the lymph node in formalin. Cytological evaluation of lymph node impression smears is performed after Wright staining, while histopathological analysis is conducted on fixed, sectioned lymph nodes stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For deep lymph nodes, fine-needle aspiration biopsies guided by ultrasound or CT can be performed for cytological analysis. Immunohistochemical staining and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can further determine lymphoma subtypes from tissue sections.

Immunoenzymatic techniques and flow cytometry enable the detection of differentiation antigens on lymphoma cells, facilitating phenotypic analysis and aiding in further lymphoma classification. Chromosomal banding analysis during metaphase is useful for diagnosing certain NHL subtypes.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Progressive, painless lymphadenopathy warrants examination using lymph node impression smears, pathological sections, or material from lymph node fine-needle aspiration smears. In cases of suspected cutaneous lymphoma, skin biopsies and impression smears may aid diagnosis. Bone marrow biopsies and smears can determine bone marrow involvement when abnormalities in blood cell counts, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels, or skeletal involvement are detected. A definitive diagnosis and lymphoma classification are based on histopathological findings. Further classification should utilize techniques such as monoclonal antibody analysis, cytogenetic studies, and molecular biology, following the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid neoplasms (2016 edition).

Staging Diagnosis

After histopathological diagnosis and classification according to subtype, the extent of lymphoma dissemination must be assessed following the Ann Arbor clinical staging system proposed for Hodgkin lymphoma (1971).

Differential Diagnosis

####Distinction from Other Causes of Lymphadenopathy

Localized lymphadenopathy requires exclusion of lymphadenitis and metastatic malignant tumors. Tuberculous lymphadenitis typically presents as bilateral involvement in the cervical region, with affected lymph nodes fusing together and adhering to surrounding tissues. In late stages, caseation and rupture may lead to sinus formation.

Lymphomas Presenting with Fever

Differentiation is necessary from conditions such as tuberculosis, septicemia, connective tissue diseases, necrotizing lymphadenitis, and hemophagocytic syndromes.

Extranodal Lymphomas

Extranodal lymphomas should be distinguished from other malignant tumors specific to the corresponding organs involved.

Treatment

The tendency of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) to arise in multiple sites reduces the prognostic value of clinical staging and diminishes the therapeutic effect of extended-field radiotherapy compared to Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), thereby establishing chemotherapy as the cornerstone of its treatment strategy.

Combined Modality Therapy with Chemotherapy as the Primary Approach

Indolent Lymphomas

B-cell indolent lymphomas include small lymphocytic lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma. T-cell indolent lymphomas are represented by mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. Indolent lymphomas progress slowly, and while both chemotherapy and radiotherapy are effective, achieving complete remission remains challenging. For stages I and II, survival of up to 10 years may be seen following radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Some patients experience spontaneous tumor regression, supporting palliative approaches involving observation and monitoring for stages III and IV. In cases of disease progression, oral administration of chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide can be utilized, particularly for elderly patients. Bendamustine has shown efficacy in controlling various subtypes of indolent lymphomas due to its ability to target cells in the G0 phase.

Chemotherapy for stages III and IV may result in multiple relapses. Nonetheless, median survival can reach 10 years, and combination regimens such as COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) or CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) are effective. For progressive, refractory cases, the FC (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) regimen may be considered.

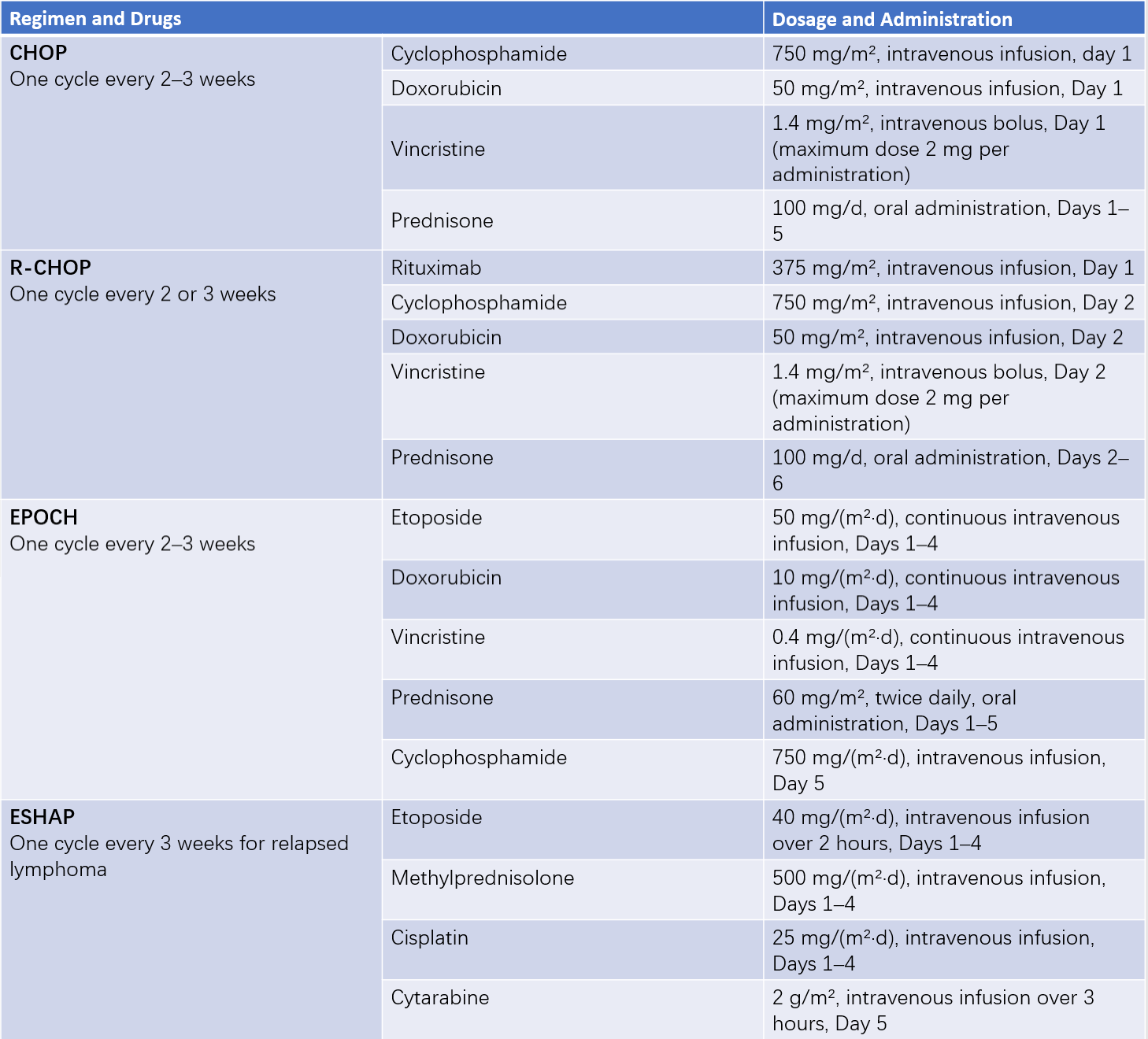

Table 2 Common combination chemotherapy regimens for non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Note: Drug dosages are for reference only and should be adjusted based on specific clinical situations.

Aggressive Lymphomas

B-cell aggressive lymphomas include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and Burkitt lymphoma. T-cell aggressive lymphomas include angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Regardless of stage, chemotherapy remains the primary treatment for aggressive lymphomas. Local radiotherapy with extended fields (25 Gy) may supplement chemotherapy in cases of residual masses, large localized tumors, or central nervous system involvement.

The CHOP regimen represents the standard treatment for aggressive NHL. Each cycle lasts 2–3 weeks, and if no response is achieved after 4 cycles, the treatment regimen should be altered. Once complete remission is attained, 2 additional consolidation cycles are administered, with a minimum of 6 total cycles required. Maintenance therapy over the long term does not provide additional benefits. The 5-year progression-free survival rate with CHOP ranges from 41% to 80%.

The R-CHOP regimen, which includes the addition of rituximab (375 mg/m2) prior to chemotherapy, has demonstrated superior efficacy and is now a classic regimen for treating DLBCL. Follow-up over the past 10 years has shown that 8 cycles of R-CHOP therapy improve overall survival in DLBCL patients by as much as 4.9 years.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma progress rapidly and can result in death within weeks or months without aggressive treatment. Intensive chemotherapy regimens should be employed. High-dose cyclophosphamide-based regimens have shown potential for curative outcomes in Burkitt lymphoma and should be considered.

Novel Therapies

Novel therapies include:

- Lenalidomide: An immunomodulatory agent, used in combination with chemotherapy.

- Chidamide: A histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, utilized for the treatment of T-cell lymphomas.

- Ibrutinib: A Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, effective in treating mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

For patients with relapsed or refractory disease, second-line regimens that avoid cross-resistance with the initial therapy are typically employed. Salvage regimens include ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), DHAP (dexamethasone, carboplatin, high-dose cytarabine), MINE (ifosfamide, mitoxantrone, etoposide), and the Hyper-CVAD regimen (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone).

Biological Therapy

Monoclonal Antibodies

Most NHL cases are B-cell in origin, with 90% expressing CD20. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) also demonstrates high-density expression of CD20. CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas can be treated using CD20 monoclonal antibodies, such as rituximab. When combined with chemotherapy, this approach significantly increases complete remission rates and prolongs disease-free survival in both indolent and aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Rituximab has also been used for in vivo purging of B-cell lymphomas before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), enhancing the efficacy of transplantation therapy.

Interferon

Interferon exhibits partial efficacy in treating conditions such as mycosis fungoides.

Anti-Hp Therapy

For early-stage gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, treatment targeting Helicobacter pylori (Hp) can lead to symptom improvement and, in some patients, complete regression of the lymphoma.

CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy

CAR-T cell therapy, or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, offers renewed hope for survival and long-term remission in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphomas. This immunotherapy involves genetic engineering to modify a patient's T cells by introducing genes coding for chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), enabling these cells to recognize and target tumor cells specifically. CAR-T cells can release multiple effector cytokines to efficiently kill tumor cells through immune mechanisms, achieving therapeutic effects against malignant lymphomas.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

Patients under the age of 60 with normal organ function, short remission periods, or refractory and easily relapsing aggressive lymphomas may benefit from HSCT if the first-line therapy proves effective. HSCT seeks to maximize tumor cell eradication and achieve prolonged remission and disease-free survival.

Surgical Treatment

Splenectomy may be considered in cases of hypersplenism if surgical indications are present. This procedure can improve blood counts and create favorable conditions for subsequent chemotherapy.

Prognosis

Significant advances have been made in the treatment of lymphomas, and HL has become one of the malignancies curable through chemotherapy.

The 5-year survival rate for stage I and II HL exceeds 90%, while for stage IV, it stands at 31.9%. Prognosis is poorer in patients with systemic symptoms compared to those without. Both children and the elderly generally have worse outcomes relative to young and middle-aged adults. Women tend to exhibit better prognoses after treatment than men.

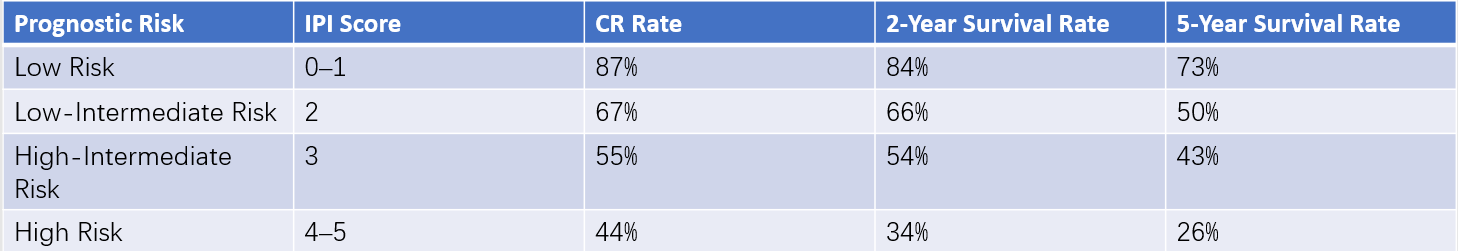

Table 3 Prognosis for non-Hodgkin lymphoma

In 1993, ShiPP and colleagues proposed the International Prognostic Index (IPI) for NHL, dividing prognosis into four categories: low risk, low-intermediate risk, high-intermediate risk, and high risk. The IPI scoring system remains in use today and is applicable to all NHL subtypes. Five adverse prognostic factors, each assigned one point, include age over 60 years, stage III or IV disease, involvement of two or more extranodal sites, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of ≥2, and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. The IPI score can provide an initial assessment of the prognosis for individual NHL cases.