Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is an acquired clinical syndrome that arises in the context of conditions such as infections, malignancies, obstetric complications, or trauma. It is characterized by excessive activation of intravascular coagulation and widespread microthrombosis in response to damage to the microvascular system caused by pathogenic factors. This results in the massive consumption of coagulation factors and secondary hyperfibrinolysis, manifesting as a clinical syndrome marked by bleeding and microcirculatory failure. The incidence of DIC varies across different underlying diseases, with an overall occurrence rate of approximately 1 in 1,000 hospitalized patients.

Etiology

DIC can develop secondary to a variety of diseases. The most common causes of acute and subacute DIC include:

- Infections: Pathogens such as Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, viruses, rickettsia, and protozoa are implicated.

- Malignancies: Hematologic cancers, particularly acute leukemia and lymphoma, are frequently associated with DIC.

- Obstetric Complications: Conditions such as amniotic fluid embolism, septic abortion, severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, HELLP syndrome, and placental abruption commonly lead to DIC.

Other causes include severe trauma, extensive burns, acute pancreatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, snake bites, heatstroke, and certain drug toxicities. Chronic DIC is primarily associated with solid malignant tumors, dead fetus syndrome, and advanced liver disease.

Pathogenesis

Excessive thrombin generation and secondary hyperfibrinolysis are the central mechanisms in the development of DIC. Excess thrombin production depletes coagulation factors and binds to thrombin receptors on platelets and endothelial cells, which activates platelets and induces the release of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) from endothelial cells, thereby activating plasmin for fibrinolysis. In most cases, the procoagulant stimulus in DIC is mediated by tissue factor (TF). Increased TF levels result from several processes, including excessive TF entering blood circulation due to tissue injury, secretion of TF or TF-like substances by malignant tumor cells, or upregulated TF expression on endothelial cells and monocytes induced by inflammatory mediators. TF triggers the extrinsic coagulation pathway, while exposure of negatively charged collagen following endothelial injury in the microvascular system activates the intrinsic coagulation pathway. Both pathways lead to thrombin formation, resulting in platelet activation and fibrin formation.

In acute decompensated DIC, the rate of coagulation factor consumption exceeds the liver's synthetic capacity, and thrombocyte depletion surpasses the compensatory ability of bone marrow megakaryocytes to produce and release platelets. Laboratory findings in such cases include prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), along with reduced platelet counts. Excess fibrin generated during DIC induces a compensatory process of secondary hyperfibrinolysis, increasing levels of fibrin(ogen) degradation product (FDP). FDP acts as a potent anticoagulant and further exacerbates bleeding symptoms associated with DIC. Deposition of fibrin within blood vessels may result in microangiopathic hemolytic fragmentation of red blood cells, leading to the appearance of fragmented red cells on blood smears. Thrombosis in microvessels during DIC can cause tissue necrosis and damage to end-organs.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of DIC includes features of the underlying disease along with symptoms attributable to the DIC itself. Manifestations of the underlying disease vary depending on its nature, severity, duration, and causative factors. The main clinical features of DIC include the following:

Bleeding

Bleeding is often severe and widespread in acute DIC, with symptoms such as petechiae, ecchymosis, and hematomas at injection sites. Oozing of blood from venipuncture sites is particularly characteristic. Some patients exhibit distinctive ischemic skin discoloration, described as "map-like" cyanosis of the extremities. Other forms of bleeding include gingival bleeding, epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary hemorrhage, hematuria, vaginal bleeding, and more. Intracranial hemorrhage is one of the leading causes of mortality in DIC.

Microcirculatory Disturbance

DIC often results in tissue and organ hypoperfusion that is disproportionate to the amount of blood loss. Mild cases may present as transient hypotension, while severe cases lead to shock.

Thrombosis and Embolism

Systemic or localized microvascular thrombosis may occur and tends to affect organs such as the kidneys, lungs, adrenal glands, skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, brain, pancreas, and heart. Symptoms vary depending on the site of thrombosis; for example, pulmonary embolism can result in respiratory distress, renal thrombosis may lead to kidney failure, and ischemic necrosis may manifest as gangrene of fingers or toes.

Intravascular Hemolysis

Intravascular hemolysis occurs in approximately 10-20% of DIC cases, with symptoms such as jaundice, anemia, hemoglobinuria, oliguria, or even anuria. Blood smears may reveal fragmented or deformed red blood cells.

Laboratory and Specialized Tests

Hematological Tests

Complete blood count (CBC) can provide partial evidence for acute bleeding, accelerated red blood cell destruction, or underlying conditions such as leukemia. A decrease in platelet count often occurs early in acute DIC. Platelet count reduction tends to be more pronounced in DIC caused by infections. Progressive declines in platelet levels carry greater significance for the diagnosis of DIC.

Coagulation and Fibrinolysis Tests with Result Analysis

Results commonly include prolonged prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and thrombin time (TT); a decrease in plasma fibrinogen concentration; and increased levels of fibrin degradation products (FDP) and D-dimer. A positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test (3P test) may also be observed. Fibrinogen levels vary depending on the type and stage of DIC. As an acute-phase protein, fibrinogen levels may be normal or mildly elevated in the early stages of sepsis-induced or other underlying disease-triggered DIC due to increased fibrinogen production, while continued monitoring often reveals a decreasing tendency. DIC secondary to acute promyelocytic leukemia is often associated with a marked reduction in fibrinogen levels. Therefore, a normal fibrinogen level does not exclude the possibility of DIC.

Hyperfibrinolysis in DIC is driven by fibrin clots and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA). Though FDP levels increase in DIC, this finding is not specific, whereas elevated D-dimer levels are more specific for the diagnosis of DIC. In challenging cases or when underlying diseases affect routine test results, additional markers such as thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), soluble thrombomodulin (sTM), and α2-antiplasmin (α2-AP) may help confirm or exclude the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

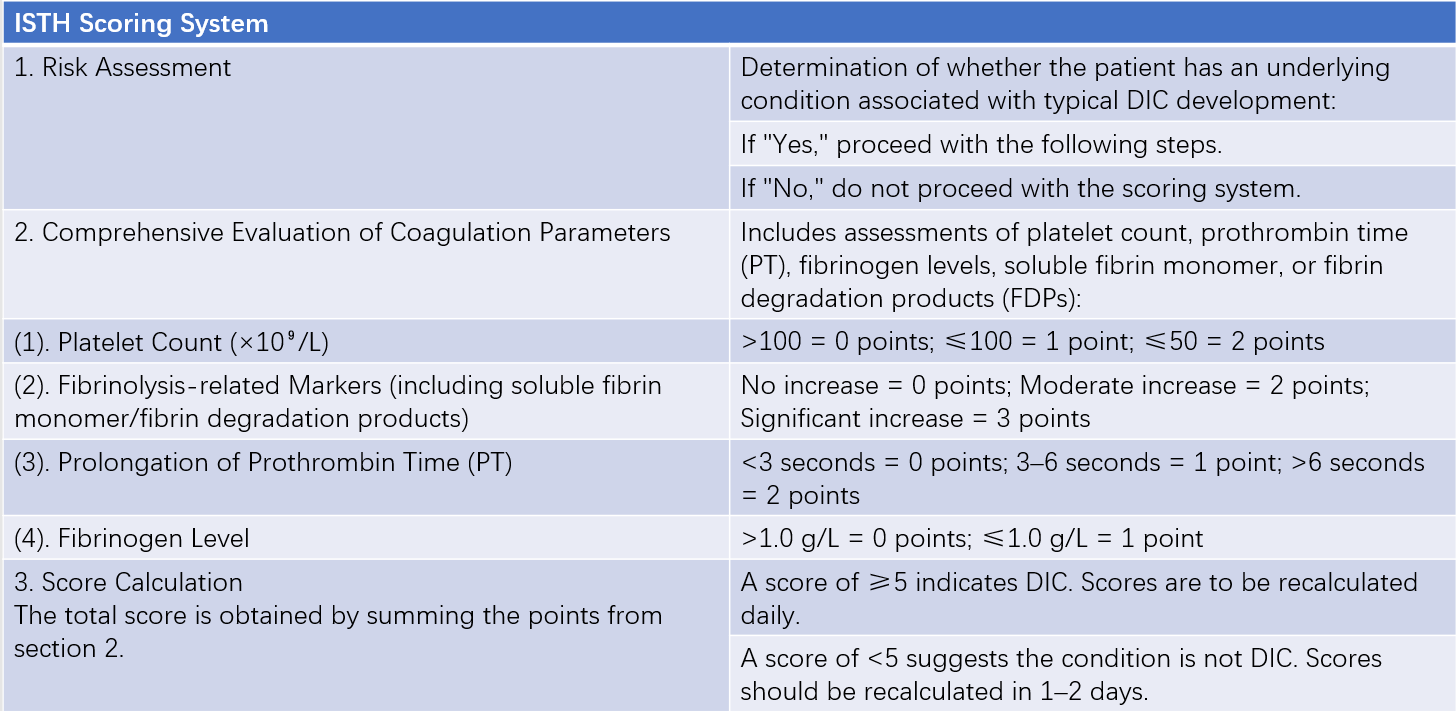

DIC has a complex and variable clinical presentation, and no single laboratory parameter offers both high sensitivity and high specificity. Diagnosing DIC poses significant challenges in clinical practice. In 2001, the DIC Subcommittee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) proposed a scoring system to diagnose overt DIC.

Table 1 ISTH scoring system for the diagnosis of overt DIC

The scoring system incorporates coagulation parameters that are simple to obtain. It considers multiple pathophysiological mechanisms of DIC, including coagulation factor consumption, platelet consumption, and hyperfibrinolysis, making it a practical diagnostic tool. However, ISTH does not specify thresholds distinguishing moderate and significant increases in fibrinolysis-related markers. In the literature, fibrinolysis-related values 5–10 times the normal reference range are generally considered moderate increases, while values exceeding 10 times are classified as significant increases.

Differential Diagnosis

Severe Liver Disease

Various coagulation factors are reduced in severe liver disease. However, a history of liver disease is often present, along with significant symptoms of jaundice and liver function impairment. Platelet reduction in liver disease tends to be mild or fluctuating, and the detection rate of soluble fibrin monomer is low, which can help differentiate it from DIC. It is important to recognize cases in which severe liver disease coexists with DIC.

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

TTP is characterized primarily by thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolysis but lacks evidence for the consumption of coagulation factors or hyperfibrinolysis, which distinguishes it from DIC.

Primary Hyperfibrinolysis or "Pathological" Hyperfibrinolysis

Laboratory findings include hypofibrinogenemia, increased FDP levels, abnormal PT, APTT, and TT, as well as reduced factor V (FV) and factor VIII (FVIII:C). Unlike DIC, platelet counts are usually normal in primary hyperfibrinolysis, D-dimer levels are normal or only mildly elevated, and the plasma protamine paracoagulation (3P test) is negative.

Treatment

The treatment of DIC follows these principles:

Elimination of the Underlying Cause and Active Management of the Primary Disease

Treating the underlying condition is critical in managing any type of DIC. For DIC caused by infections, appropriate and sufficient antibiotics should be administered, with efforts to identify the site of infection and the bacterial strain as soon as possible. For DIC associated with malignancies, corresponding treatments such as chemotherapy should be undertaken.

Restoration of Coagulation Homeostasis

Patients with DIC require anticoagulation therapy to prevent or treat thrombosis and to minimize the further consumption of coagulation factors and platelets. Heparin therapy serves as the principal anticoagulant intervention. Low-dose heparin provides sufficient anticoagulant effects and has an anti-inflammatory role, while avoiding the increased bleeding risk associated with higher doses. Administration methods include:

- Unfractionated Heparin (UFH): The total daily dose typically does not exceed 12,500 units, with individual doses of no more than 2,500 units every 6 hours, administered either intravenously or subcutaneously. The treatment duration is usually 3–5 days, depending on the clinical condition.

- Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH): Administered at a dose of 3,000–5,000 units daily via subcutaneous injection, with a course of treatment generally lasting 3–5 days, adjusted based on disease severity.

Anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated in hemorrhagic DIC.

Replacement Therapy

Replacement therapy involves the transfusion of platelets, cryoprecipitate, or fresh frozen plasma. For significant consumption of coagulation factors and inhibitors, when the PT (prothrombin time) is prolonged by 1.3–1.5 times the upper limit of normal, fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate may be administered. When fibrinogen levels fall below 1.0 g/L, cryoprecipitate transfusion is necessary to replenish fibrinogen levels. Plasma replacement therapy aims to maintain PT within 2–3 seconds above the normal range and elevate fibrinogen levels above 1.0 g/L. Platelet transfusion is recommended when the platelet count drops below (10–20) × 109/L, or below 50 × 109/L in patients with significant bleeding symptoms.

Organ Support Therapy

DIC is closely associated with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Comprehensive organ support therapies are critical in the rescue of patients in the middle-to-late stages of DIC. Therapies such as fluid replacement, correction of hypotension and acidosis, and oxygen supplementation help improve blood flow and increase oxygen content in the microcirculation. Close monitoring of pulmonary, cardiac, and renal functions aids in guiding timely implementation of supportive measures. The use of vasoactive agents improves organ perfusion, preserves renal function, and helps maintain electrolyte balance.