Acromegaly and gigantism are syndromes caused by excessive secretion of growth hormone (GH). When this occurs before puberty, it manifests as gigantism, which is relatively rare. When it occurs after puberty, it presents as acromegaly, characterized primarily by the overgrowth of bones, soft tissues, and internal organs, and it is more common. In rare cases, if the condition begins before puberty but progresses into adulthood, it results in a combination of features from both gigantism and acromegaly, known as acromegalic gigantism. This section primarily focuses on acromegaly. The annual incidence is approximately 10 cases per 1 million, with no significant difference in prevalence between genders.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The condition is most commonly associated with pituitary tumors that secrete GH. Tumors outside the pituitary gland, as well as genetic forms of acromegaly, are much less frequent.

Pituitary Tumors

These account for over 95% of cases. Based on the density of GH-secreting granules and the expression patterns of cytokeratin in tumor cells, they can be pathologically classified into densely granulated somatotroph adenomas (DGSA) and sparsely granulated somatotroph adenomas (SGSA). DGSA is more common in individuals over 50 years of age and is mainly composed of large, eosinophilic cytoplasm-dense cells. Immunohistochemical staining reveals strong, diffuse GH expression and perinuclear cytokeratin positivity with low-molecular-weight proteins. This subtype often responds well to somatostatin analog treatments. SGSA, on the other hand, is more common in younger patients and consists mainly of chromophobic or weakly eosinophilic cells. Over 70% of tumor cells in this subtype exhibit intranuclear fibrous bodies (cytokeratin aggregates near the nucleus). GH expression is weak and patchy, and these tumors demonstrate a poor response to somatostatin analogs.

Extrapituitary Tumors

These include ectopic GH-secreting tumors, such as pancreatic islet cell carcinoma, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) tumors, hypothalamic hamartomas, bronchial carcinoids, and others.

Genetic-Related Acromegaly

Hereditary conditions associated with acromegaly include multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes (MEN1 and MEN4), familial isolated pituitary adenomas, Carney complex, and McCune-Albright syndrome.

The exact pathogenesis of acromegaly remains incompletely understood. Around 40% of sporadic GH-secreting adenomas are linked to point mutations in the Gsα protein. When the GNAS gene undergoes such mutations, Gsα becomes constitutively active, triggering the development of GH-secreting tumors.

Clinical Manifestations

Gigantism

Gigantism typically begins in childhood and is characterized by a height significantly exceeding that of peers. Growth often continues until puberty when the epiphyseal growth plates close, with final heights reaching 1.8 meters (females) or 2.0 meters (males) or greater. Soft tissue overgrowth can result in coarse facial features and thickening of the hands and feet. Progressive pituitary tumors may lead to hypopituitarism, causing symptoms such as fatigue, generalized weakness, hair loss, and reduced libido. Excess GH can also impair glucose tolerance or cause diabetes, along with secondary cardiovascular complications.

Acromegaly

The clinical manifestations of acromegaly depend on tumor type, size, growth rate, GH secretion levels, and the extent of pressure on adjacent tissues. Patients often exhibit not only excess GH secretion but also partial deficiencies in the secretion of gonadotropins, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

Effects of Excessive GH

Skeletal and Joint Changes

Prominent brow bones and cheekbones, hypertrophy of the frontal bone, enlargement and protrusion of the jaw (leading to wide spacing of teeth and difficulty with occlusion), and protrusion of the occipital bone can be seen. Chest deformities include sternal prominence, elongated and widened rib ends (bead-like appearance), and an increased anteroposterior chest diameter resembling a barrel-shaped chest. Vertebrae become elongated, widened, and thickened, with disproportionate anterior overgrowth leading to kyphosis or scoliosis. Hyperplasia of bone tissue around intervertebral foramina can compress nerve roots, causing back pain. Hands and feet become broad and thick, resembling spades, and fingers and toes widen. Flat feet may develop. Large joints often exhibit cartilage overgrowth, and finger joint bones may show signs of hyperplasia, sometimes accompanied by minor non-inflammatory effusion. Bone and joint symptoms, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, back pain, and joint pain in the extremities, are common.

Skin and Soft Tissues

Changes in the skin are most pronounced in the head and facial region and, together with skeletal alterations, contribute to the characteristic facial appearance of acromegaly. Skin and soft tissue thickening are prominent, with deep wrinkles on the forehead and reduced skin creases. Other changes include an enlarged nose, thickened lips, macroglossia (enlarged tongue), thick and elongated vocal cords, and thickened tonsils, uvula, and soft palate. These features lead to a deep voice, a coarse voice in women, and the development of snoring during sleep. The external ears may become thickened, and the tympanic membrane may also thicken, occasionally causing eustachian tube obstruction, tinnitus, or hearing loss. Sebaceous gland hyperplasia results in oily skin, which may also show pigmentation, acanthosis nigricans, or hirsutism. Enlarged sweat glands lead to excessive sweating, an important indicator of active disease. Enlarged hair follicles can result in hypertrichosis in women. Some patients also develop skin tags or multiple neurofibromas.

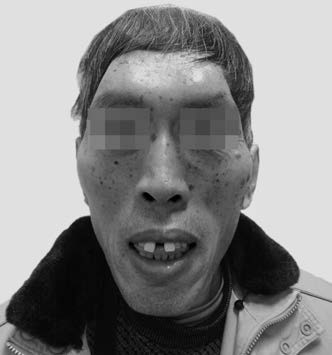

Figure 1 A patient with acromegaly caused by a pituitary growth hormone-secreting tumor

The patient exhibits thickened nasal and lip features, prominent brow ridges and cheekbones, widened interdental spaces with difficulty in biting, and skin hyperpigmentation.

Abnormal Glucose Metabolism

Excess GH can induce insulin resistance, with approximately 60% of patients showing impaired glucose tolerance and about 30% developing diabetes mellitus.

Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism

Serum phosphorus levels are significantly elevated, while serum calcium levels are typically within the normal range or at the higher end of normal.

Cardiovascular System

Hypertension occurs in 33% to 46% of cases, with diastolic pressure being more prominently affected and the incidence increasing with age. Other cardiovascular manifestations include arrhythmias, myocardial hypertrophy, cardiomegaly, reduced left ventricular diastolic function, and atherosclerosis.

Respiratory System

Common symptoms include snoring, breath-holding, drowsiness, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and dyspnea upon exertion.

Reproductive System

Men may experience reduced libido and erectile dysfunction, while women may suffer from decreased libido, infertility, menstrual irregularities, or amenorrhea. Galactorrhea may also occur in some cases.

Tumorigenic Effects

Patients with GH-secreting tumors may have an increased incidence of conditions such as colorectal polyps, colorectal cancer, thyroid cancer, and lung cancer.

Compression Symptoms from GH-Secreting Tumors

Large pituitary tumors can compress or invade surrounding tissues, causing hypopituitarism as well as symptoms such as headache, visual field defects, blurred vision, reduced visual acuity, hypothalamic dysfunction, and even pituitary apoplexy.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The onset of acromegaly is relatively insidious, and many patients are not diagnosed until 7 to 10 years after the onset of symptoms. Acromegaly is often associated with varying degrees of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and its mortality rate is significantly higher than in the general population. Early detection, accurate diagnosis, and timely treatment are therefore crucial for improving patient outcomes.

Qualitative Diagnosis

Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1)

Serum IGF-1 is the best marker for reflecting chronic GH over-secretion. Unlike serum GH, IGF-1 levels exhibit minimal variations over 24 hours, reliably indicating the biological activity of GH. Elevated IGF-1 levels in patients with typical clinical manifestations of acromegaly are sufficient to confirm the diagnosis. However, it is important to note that IGF-1 levels are lower in older adults compared to younger populations. Additionally, conditions such as hypothyroidism, malnutrition, liver or kidney failure, and oral estrogen use can lower IGF-1 levels. In atypical cases, GH suppression tests may be required for confirmation.

Growth Hormone (GH)

Serum GH Levels

Under physiological conditions, GH is secreted in a pulsatile pattern with circadian rhythmicity. Its levels increase significantly during exercise, stress, or episodes of acute hypoglycemia. In patients with acromegaly, however, GH secretion loses this rhythmicity, total GH secretion over a 24-hour period increases, and the frequency of pulsatile secretion rises. GH levels may also be elevated in patients with poorly controlled diabetes, renal failure, malnutrition, or during stress or sleep, making random GH measurements unreliable for diagnosis.

GH Suppression Test

The "gold standard" for definitive diagnosis of acromegaly and gigantism is the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). It also serves as a commonly used benchmark for evaluating responses to treatment, including medications, surgery, and radiotherapy. In this test, the patient consumes 75 grams of glucose, and blood samples are taken at −30, 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after glucose ingestion to assess GH levels. In most cases of acromegaly, GH is not suppressed (failure to lower serum GH to <1 µg/L during OGTT is diagnostic). Other dynamic tests, such as growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) stimulation, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation, dopamine suppression, and arginine suppression tests, can also provide diagnostic value in specific circumstances.

Evaluation of Other Pituitary Hormones

Measurement of serum prolactin (PRL), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), along with assessment of corresponding target gland functions, is necessary to evaluate for excessive secretion or deficiencies of other pituitary hormones. If a patient exhibits symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, and excessive thirst, posterior pituitary function should be assessed as well.

Localization Diagnosis

MRI

Pituitary MRI serves as the preferred imaging modality. It provides high tissue resolution, allowing for detailed visualization of intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and cystic changes within pituitary adenomas. MRI can also display the relationship between the tumor and adjacent structures, including compression of the optic chiasm, cavernous sinus involvement, or invasion of surrounding tissues.

CT

Pituitary CT is particularly sensitive in evaluating bony destruction of the sella turcica and detecting calcifications within or around lesions. However, its sensitivity in identifying microadenomas is relatively low. Additionally, thoracic or abdominal CT may be used to diagnose or exclude extrapituitary tumors.

Other Imaging Studies

If necessary, diagnostic tools such as radionuclide-labeled octreotide imaging or positron emission tomography (PET) can aid in diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Assessment of Comorbidities

All patients with acromegaly require evaluation for associated comorbidities. These assessments include checks for blood pressure, lipid profile, blood glucose levels, electrocardiogram (ECG), cardiac ultrasound, and sleep breathing function. Colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer may also be considered. For patients with palpable thyroid nodules, thyroid ultrasound is necessary. Long-term monitoring and strict management are essential for those with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, or sleep apnea.

Differential Diagnosis

Atypical cases should be differentiated from other conditions:

Acromegaly/Gigantism Caused by Non-Pituitary GH-Secreting Tumors

These primarily include tumors that secrete growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) or non-GH-secreting pituitary tumors. Carcinoid tumors, pancreatic carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, endometrial carcinoma, adrenal carcinoma, and pheochromocytoma can all secrete GHRH, leading to excessive GH secretion. Due to their short clinical course, these conditions generally lack the typical features of acromegaly or gigantism. Elevated GH and IGF-1 levels are not suppressed by glucose, but serum GHRH levels are increased. In contrast, patients with pituitary GH-secreting tumors exhibit normal or decreased GHRH levels. Additionally, non-GH-secreting pituitary tumors, such as prolactinomas, ACTH-secreting tumors, or TSH-secreting tumors, may produce low levels of GH. These cases present with mild or subclinical acromegaly or gigantism.

Constitutional Tall Stature or Overgrowth Syndromes

Fetal overgrowth is often observed in large infants born to diabetic mothers, as well as in conditions such as cerebral gigantism (Sotos syndrome) or Weaver syndrome. Postnatal overgrowth can occur in familial tall stature or syndromes such as McCune-Albright syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, fragile X syndrome, or homocystinuria.

Isolated Prognathism

This condition is often confused with early-stage acromegaly but is characterized by normal GH and IGF-1 levels.

Pachydermoperiostosis

This condition shows familial clustering and predominantly affects young males. It resembles acromegaly in appearance, with enlargement of the hands and feet, coarse skin, enlarged pores, and excessive sweating. However, X-rays demonstrate the characteristic findings of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, and imaging reveals no pituitary tumors, while GH and IGF-1 levels remain normal.

Gestational Facial Changes

Some pregnant women may develop coarse facial features during pregnancy, accompanied by pituitary gland enlargement, visual field changes, or diabetes mellitus. However, these symptoms typically resolve within weeks after delivery.

Treatment

Treatment objectives:

- Attain control of GH-related biochemical markers.

- Reduce tumor size and prevent recurrence.

- Manage comorbidities related to cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic systems.

- Preserve pituitary function and restore endocrine balance.

The main treatment options include surgery, medication, and radiation therapy.

Surgical Treatment

Transsphenoidal surgery is the first-line treatment for GH-secreting tumors, regardless of tumor size or invasiveness. Microadenomas confined to the sella turcica (diameter <10mm) are particularly suitable for surgical removal. However, the cure rate for macroadenomas, especially those extending suprasellar or into the cavernous sinus, is lower. The main goal of surgery is tumor removal. The cure rate for microadenoma resection can reach 90%, whereas the rate drops below 50% for macroadenomas. Potential surgical complications include diabetes insipidus, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, meningitis, and hypopituitarism.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological therapy is an option for patients with insufficient surgical outcomes, those who are unsuitable for surgery (e.g., due to poor overall health), or those unwilling to undergo surgery. The main drug classes include somatostatin analogs, dopamine receptor agonists, and GH receptor antagonists.

Somatostatin Analogs

Also known as somatostatin receptor ligands (SRLs), these drugs bind to somatostatin receptors on tumor cells, inhibiting GH secretion. Long-acting octreotide is initiated at 20mg and can be increased to a maximum dosage of 30mg. Long-acting lanreotide begins at 90mg and can be increased to a maximum of 120mg. Both drugs are administered as deep intramuscular injections once every 4 weeks. Regular evaluations, including GH and IGF-1 measurements, are necessary to adjust dosages based on the patient’s condition. SRLs are generally well tolerated, though some patients may experience nausea, abdominal discomfort, bloating, diarrhea, or fat malabsorption in the initial stages of treatment, which typically resolve spontaneously. SRL therapy results in normalization of GH and IGF-1 levels in 40%–70% of patients and tumor volume reduction in 70%–80% of cases.

Dopamine Receptor Agonists

Dopamine receptor agonists (DRAs) bind to D2 receptors on tumor cells, suppressing GH secretion. While DRAs are less effective than somatostatin analogs, their advantage lies in oral administration. Cabergoline is initiated at 0.5mg once per week and can be gradually increased to 2mg per week if needed. Bromocriptine starts at 1.25mg per dose, administered 2–3 times daily, and may be progressively increased to 10–20mg daily based on the patient’s condition.

GH Receptor Antagonists

GH receptor antagonists (GHRAs) competitively bind to GH receptors, blocking the biological effects of GH and reducing serum IGF-1 levels. Pegvisomant is administered via subcutaneous injection at an initial dose of 10mg/day, with potential adjustments to 15–30mg/day depending on the clinical response.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is slow to take effect, has limited benefits, and carries a high risk of side effects. It is typically considered a third-line treatment. It is reserved for cases where tumors cannot be completely resected surgically or where pharmacological therapy fails to control tumor growth. While radiation therapy can effectively lower GH and IGF-1 levels, its effects may not become apparent until 6 months to 2 years after treatment.

Prognosis and Treatment Evaluation

Patients with acromegaly generally have poor prognoses, with high morbidity and mortality rates. After treatment, ongoing follow-up is required to monitor clinical symptoms, biochemical markers (e.g., serum IGF-1 levels), and imaging results (e.g., pituitary MRI).