Growth hormone deficiency short stature, also known as childhood growth hormone deficiency (GHD), refers to a growth disorder in children due to a lack of growth hormone secretion from the anterior pituitary or insufficient biological effects of growth hormone. It can present as isolated growth hormone deficiency or may be accompanied by deficiencies of other anterior pituitary hormones. Based on etiology, it can be classified as idiopathic, acquired, or genetic; and based on the affected site, it can be categorized as hypothalamic or pituitary.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Idiopathic GHD

The cause of this condition is unknown. It may involve functional or structural abnormalities of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis resulting in insufficient growth hormone (GH) secretion. Some patients experience elevated GH levels and accelerated growth following treatment with growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), suggesting a hypothalamic origin. In some cases, a perinatal history of complications such as breech delivery, transverse lie, or birth asphyxia is noted, which may reflect fetal positioning issues caused by GHD.

Acquired GHD

This condition can be secondary to hypothalamic-pituitary abnormalities, including congenital pituitary anomalies or tumors of the central nervous system (such as craniopharyngiomas, germ cell tumors, pituitary adenomas, meningiomas, gliomas, Rathke’s cysts, or arachnoid cysts). Other causes include intracranial infections (e.g., encephalitis or meningitis), granulomatous diseases, surgical trauma, radiation-induced damage, or mechanical injury, which may affect the structure and function of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, leading to acquired growth hormone deficiency.

Genetic GHD

At least 1/3 of GHD cases have a family history and may exhibit autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked inheritance patterns. Molecular biology research has identified gene mutations in transcription factors (e.g., POU1F1, PROP1) involved in hypothalamic-pituitary axis development, in the growth hormone gene (GH1), or in genes involved in growth hormone receptor and downstream signaling pathways. Mutations in transcription factors often lead to combined pituitary hormone deficiencies, including GH, PRL, TSH, and gonadotropins.

Growth Hormone Insensitivity Syndrome

This syndrome involves resistance of target cells to GH, resulting in short stature. It is typically inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. The causes are diverse, with most cases involving GH receptor gene mutations (Laron syndrome) and others due to post-receptor signaling defects, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) gene mutations, or IGF-1 receptor abnormalities.

Clinical Manifestations

Growth Retardation

At birth, height and weight are usually within normal limits, but after a few months, physical growth slows, often going unnoticed. By 2–3 years of age, a significant height discrepancy with peers becomes evident. Growth does not cease entirely but proceeds at a markedly reduced rate, falling below 1 SD of normal growth velocity (e.g., annual growth < 5.5 cm from age 2–4 years or < 4–5 cm from age 4 years to puberty). The body is generally proportionate, and individuals retain a childhood body shape and appearance into adulthood. Nutritional status tends to be good. Adult height typically does not exceed 130 cm, but final height depends on the degree and duration of GH deficiency.

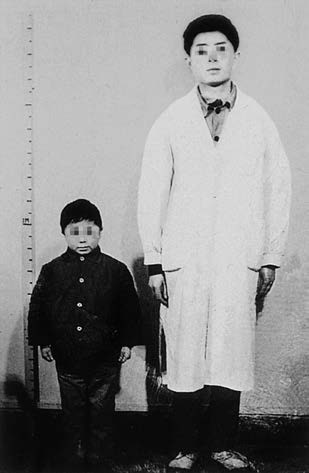

Figure 1 Growth hormone deficiency short stature

Comparison between a patient with growth hormone deficiency short stature and a normal individual of the same age.

Delayed Gonadal Development

During puberty, sexual organs often fail to develop, secondary sexual characteristics are absent, voices remain high-pitched, and individuals exhibit a tendency toward obesity. Males may present with micropenis resembling that of young children, small testes, cryptorchidism, and absence of pubic and axillary hair. Females may experience primary amenorrhea, underdeveloped breasts, and small uterus and adnexa. Patients with isolated GH deficiency may demonstrate sexual organ development and secondary sexual characteristics, though these are usually delayed.

Normal Intelligence

Intellectual development is typically normal, though short stature may lead to emotional challenges such as low self-esteem or depression.

Delayed Bone Development and Abnormal Bone Metabolism

Bone age is evaluated using X-rays of the left wrist, focusing on epiphyseal ossification. Untreated GHD children show significant delays in bone age (≥2 years behind chronological age). In addition to slow skeletal maturation, reduced bone turnover, decreased bone mass, and even osteoporosis may occur. Radiographs show shortened long bones, immature bone age, delayed ossification centers, and unfused epiphyses.

Laron Syndrome (Dwarfism Syndrome)

This rare condition is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by GH receptor gene mutations. Patients exhibit severe manifestations of GH deficiency, such as short stature, blue sclera, limited elbow joint mobility, relatively large heads, saddle noses, prominent foreheads, small external genitalia and testes, and delayed sexual development. However, plasma GH levels are normal or elevated, while IGF-1 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) levels are reduced. These patients are unresponsive to exogenous GH therapy. The only effective treatment currently available is recombinant human IGF-1 replacement therapy.

Diagnosis

Primary diagnostic criteria include:

- Short stature (height below -2SD of the age- and sex-matched population mean) with slow growth velocity, possibly accompanied by clinical features such as delayed sexual development.

- Bone age assessment showing a delay of more than two years compared to chronological age.

- Measurements of serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels: Growth hormone (GH) stimulates the liver to secrete IGF-1, which mediates most of the growth-promoting effects of GH. Thus, IGF-1 levels reflect GH secretion. Six IGFBPs have been identified (IGFBP-1 to IGFBP-6), with IGFBP-3 constituting 92%, making it a reliable indicator of GH secretion.

- GH stimulation tests: As GH secretion is pulsatile, random serum GH measurements have limited diagnostic value. At least two GH stimulation tests are typically required, including methods utilizing insulin-induced hypoglycemia, levodopa, arginine, or clonidine (see Section 3 of this chapter). In complete GHD, the GH peak after stimulation is often <5 μg/L, while partial GHD is characterized by a GH peak of 5-10 μg/L.

- Exclusions of other conditions causing growth retardation, such as cretinism, chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Turner syndrome), or chronic liver and kidney diseases.

After a definitive diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency short stature, further investigation is necessary to identify the underlying cause. Tests such as visual field examinations, CT, or MRI of the sella turcica can exclude tumors. Chromosomal and genetic analyses may be performed if needed. Idiopathic cases lack obvious causes upon clinical evaluation.

Differential Diagnosis

Short Stature due to Systemic Diseases

Chronic conditions affecting the heart, liver, kidneys, gastrointestinal system, or persistent infections (e.g., tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, hookworm infection) during childhood can lead to growth impairment. Differentiation relies on the clinical manifestations of the primary disease, with normal or elevated GH and IGF-1 levels.

Constitutional Delay in Growth and Development

Growth and development are delayed compared to peers, with the onset of puberty postponed until 16–17 years, resulting in short stature. However, intelligence is normal, and there is no evidence of endocrine or chronic systemic diseases. GH and IGF-1 levels are normal. Once puberty begins, bone growth accelerates, secondary sexual characteristics develop appropriately, and final height often reaches the normal range.

Cretinism

Hypothyroidism occurring during fetal development or infancy can cause significant growth retardation, termed cretinism. Patients exhibit short stature along with other symptoms of hypothyroidism, often accompanied by cognitive impairment.

Congenital Ovarian Dysgenesis (Turner Syndrome)

Turner syndrome is a sex chromosome disorder in females caused by partial or complete absence of one X chromosome. It is characterized by short stature, underdeveloped sexual organs, primary amenorrhea, and congenital anomalies such as a webbed neck and cubitus valgus. GH levels are typically normal. The karyotype in classic cases is 45,X.

Other Conditions

These include idiopathic short stature, familial short stature, osteochondrodysplasia, intrauterine growth retardation, and syndromic disorders such as Prader-Willi syndrome.

Treatment

Human Growth Hormone (hGH)

Recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) therapy has demonstrated significant efficacy in treating growth hormone deficiency short stature. The initial dose is typically 20–50 μg/kg per day (daily formulation) administered subcutaneously at bedtime, or 0.16–0.24 mg/kg per week (weekly formulation). The dosage is adjusted based on growth velocity, IGF-1 levels, and other factors. Local and systemic side effects of rhGH injections are relatively rare and may include severe hypersensitivity reactions, water and sodium retention (e.g., resulting in edema or carpal tunnel syndrome), and mild glucose intolerance. Monitoring for allergic reactions, blood glucose, and blood pressure is necessary. Contraindications include a history of malignant tumors, intracranial hypertension, or proliferative retinopathy.

Recombinant Human IGF-1

Recombinant human IGF-1 has been used in recent years to treat severe GH insensitivity syndrome. Treatment outcomes are better with early diagnosis and intervention. The typical dosage is 80–120 μg/kg administered subcutaneously twice daily within 20 minutes of meals. The main adverse effect is hypoglycemia.

In cases of secondary growth hormone deficiency short stature, treatment should focus on addressing the underlying primary condition.