Cushing syndrome refers to a group of disorders caused by excessive secretion of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol, from the adrenal glands due to various underlying causes. Among these, Cushing disease, which results from excessive adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from the pituitary gland, is the most common type.

Etiology and Classification

ACTH-Dependent Cushing Syndrome

This category includes the following:

- Cushing Disease: Caused by excessive ACTH secretion from the pituitary gland, often due to a microadenoma and, less commonly, a macroadenoma.

- Ectopic ACTH Syndrome: Caused by non-pituitary tumors that secrete large amounts of ACTH.

- Ectopic Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) Syndrome: Caused by ectopic CRH secretion from tumors, which stimulates the pituitary to produce excessive ACTH, leading to hyperplasia of ACTH-secreting cells.

ACTH-Independent Cushing Syndrome

This category includes the following:

- Adrenal Cortical Adenoma.

- Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma.

- Primary Pigmented Nodular Adrenocortical Disease, with or without Carney syndrome.

- ACTH-Independent Bilateral Macronodular Adrenal Hyperplasia.

Clinical Manifestations

Cushing syndrome primarily results from prolonged excessive cortisol secretion, leading to severe dysfunction in protein, fat, glucose, and electrolyte metabolism, as well as abnormalities in the secretion of other hormones. The clinical manifestations are highly variable in severity. Cases caused by adrenal carcinoma or ectopic ACTH production tend to have a more rapid onset and severe progression, while those caused by adrenal adenomas or Cushing disease generally progress more gradually and present milder symptoms. The typical clinical features are as follows:

Central Obesity, Moon Face, and Plethoric Appearance

A round, red-dark face is present with increased fat deposition in areas such as the supraclavicular fossae, cervical area, and abdomen. Notably, the individual may exhibit features such as a moon face, "fish-mouth" appearance, "buffalo hump," supraclavicular fat pads, and a protuberant abdomen, with relatively thin limbs. A plethoric appearance, along with thin and translucent skin, is associated with increased visibility of capillaries, elevated red blood cell counts, and higher hemoglobin levels.

Skeletal Muscle and Nervous System Symptoms

Muscle weakness is present, often making it difficult for individuals to rise from a squatting position. Various degrees of psychological and emotional changes are observed, such as emotional instability, irritability, and insomnia. Severe cases may experience psychosis, and some may develop delusional states.

Skin Manifestations

The skin appears thin and fragile, with increased capillary fragility leading to easy bruising from minor trauma. Purple striae (width >1 cm) are commonly noted in areas such as the lower abdomen and inner thighs. Fungal infections frequently affect areas like the hands, feet, fingernails, toenails, and perianal region. Patients with ectopic ACTH syndrome or severe Cushing’s disease may show hyperpigmentation and darkening of the skin.

Cardiovascular Manifestations

Hypertension is a common feature and is related to cortisol-induced sodium retention, potassium excretion, activation of the renin-angiotensin system, enhanced vascular responsiveness to vasoconstrictive agents, suppression of vasodilatory mechanisms, and activation of mineralocorticoid receptors. Long-term hypertension can lead to complications such as left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, and cerebrovascular accidents. Coagulation abnormalities and dyslipidemia increase the risk of arterial and venous thrombosis, further contributing to cardiovascular complications.

Reduced Resistance to Infection

Prolonged cortisol hypersecretion weakens the immune system, making infections, particularly lung infections, more common. Suppurative bacterial infections may become poorly localized, leading to complications such as cellulitis or septicemia. Infections often present with muted inflammatory responses, minimal fever, and non-specific symptoms, increasing the risk of delayed diagnosis and severe outcomes.

Sexual Dysfunction

Female patients may experience excessive adrenal androgen production and cortisol-mediated suppression of pituitary gonadotropins, resulting in hirsutism, acne, oligomenorrhea, irregular menstruation, or even amenorrhea. The presence of marked virilizing features such as breast atrophy, beard growth, enlarged laryngeal prominence, and clitoromegaly raises suspicion of adrenal cortical carcinoma. Male patients may present with decreased libido, reduced penile size, and softening of the testes.

Metabolic Disturbances

Excess cortisol promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis, antagonizes insulin action, impairs peripheral glucose utilization, and increases hepatic glycogen output, leading to glucose intolerance or even diabetes mellitus. Severe hypokalemic alkalosis is often observed in cases caused by adrenal carcinoma or ectopic ACTH syndrome. Hypokalemia exacerbates weakness, and sodium retention can cause edema in some individuals. Long-standing disease may result in osteoporosis, vertebral compression fractures, or reduced stature. In children, growth and development are often impaired.

Etiologies and Clinical Features of Various Types

Cushing Disease

This is the most common type, accounting for approximately 70% of cases of Cushing syndrome. The most frequently observed pituitary lesion is an ACTH-producing microadenoma (diameter <10 mm), which is found in about 80% of Cushing disease patients. Most cases can achieve remission following surgical removal of the microadenoma. ACTH microadenomas are not entirely autonomous, as they remain suppressible by high doses of exogenous glucocorticoids and respond to CRH stimulation. Approximately 10% of cases involve ACTH macroadenomas, which may exhibit mass effects and extend beyond the sella turcica. Malignant tumors are rare and are often associated with distant metastases. In a small number of cases, the pituitary lacks tumors but exhibits hyperplasia of ACTH-producing cells, which may be due to hypothalamic dysfunction. Bilateral diffuse adrenal cortical hyperplasia is typically observed, with hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the zona fasciculata cells that produce glucocorticoids. On occasion, hyperplasia of the androgen-secreting zona reticularis cells is also observed.

Ectopic ACTH Syndrome

This condition is caused by excessive ACTH secretion from non-pituitary tumor tissues, most commonly associated with small-cell lung carcinoma, bronchial carcinoid, thymic carcinoid, or pancreatic tumors. It accounts for approximately 15% of cases of Cushing syndrome and can be classified into two clinical subtypes:

- Slowly Progressive Type: Often linked to tumors with low malignancy, such as carcinoids, with a disease course that can last for several years. The clinical features and laboratory findings are similar to those of Cushing disease.

- Rapidly Progressive Type: Characterized by highly malignant and rapidly progressing tumors. Typical clinical features of Cushing syndrome are frequently absent, while serum ACTH levels, as well as serum and urinary cortisol levels, are markedly elevated.

Adrenal Cortical Adenoma

This accounts for approximately 10%–15% of cases of Cushing syndrome and is more commonly observed in adults. Adenomas are generally round or oval in shape, with a diameter of 3–4 cm and an intact capsule. The onset is relatively slow, the disease severity is moderate, and features related to androgen excess, such as hirsutism, are rarely observed.

Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma

This accounts for less than 5% of cases of Cushing syndrome. The clinical course is severe and progresses rapidly. Tumors are typically large, with diameters of 5–6 cm or more, and may invade surrounding tissues, breaching the capsule. In advanced stages, metastases to lymph nodes, liver, lungs, or bones are common. Severe symptoms of Cushing syndrome are observed, along with significant hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis. Excess production of androgens may lead to symptoms in women, such as hirsutism, acne, clitoromegaly, and deepening of the voice. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, back pain, and flank pain are also observed, with physical examination often revealing palpable masses.

Primary Pigmented Nodular Adrenocortical Disease (PPNAD)

This condition is characterized by ACTH-independent bilateral nodular adrenal hyperplasia. It predominantly occurs in children or young adults. Some patients present with clinical features similar to those of general cases of Cushing syndrome, while others have a family history suggestive of an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, often accompanied by spotty skin and mucosal pigmentation, blue nevi, myxoma of the skin, breast, or atrium, testicular tumors, or pituitary growth hormone-secreting adenomas, collectively known as Carney syndrome. ACTH levels are low or undetectable, and high-dose dexamethasone does not suppress cortisol secretion. Adrenal size is normal or slightly increased, with numerous nodules, which may only be visible microscopically for smaller nodules or may reach up to 5 mm in diameter for larger ones. The nodules are often brown or black in color, with intervening areas of cortical atrophy. The pathogenesis is associated with mutations in the regulatory subunit 1α (PRKAR1A) of protein kinase A (PKA), leading to activation of the PKA signaling pathway.

ACTH-Independent Macronodular Adrenal Hyperplasia (AIMAH)

This condition involves bilateral adrenal enlargement with multiple benign nodules larger than 5 mm in diameter, typically without skin pigmentation. Pituitary imaging via CT or MRI reveals no abnormalities. The disease progression is slower compared to adrenal adenomas. The etiology is related to ectopic expression of receptors for gastrointestinal inhibitory peptide (GIP), luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin (LH/HCG), arginine vasopressin, or serotonin on adrenal cortical cells. Activation of these receptors by corresponding ligands leads to excessive cortisol production. For cases associated with GIP, postprandial cortisol secretion is increased, whereas morning fasting cortisol levels may be normal or even low. When associated with LH/HCG, symptoms often appear during pregnancy or postmenopausal periods.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

Clinical Presentation

A diagnosis can sometimes be made based on appearance in patients with typical symptoms and signs. However, in early or atypical cases, characteristic symptoms may not be obvious or may be overlooked, leading to a missed diagnosis, especially when patients seek medical attention for symptoms related to a single system.

Abnormal Glucocorticoid Secretion Common to All Types of Cushing Syndrome

Excessive cortisol secretion, loss of diurnal rhythm, and resistance to suppression by low-dose dexamethasone are typical.

Loss of Diurnal Rhythm

In healthy adults, plasma cortisol levels peak at around 6:00–8:00 AM and reach their lowest levels at midnight. In patients with Cushing syndrome, this diurnal rhythm is absent, with midnight plasma cortisol levels exceeding 200 nmol/L.

Increased Urinary Free Cortisol

Daily urinary free cortisol levels typically exceed 304 nmol/24 hours and reflect circulating free cortisol levels with high diagnostic value, as interference from other pigments is minimal.

Low-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test

Oral doses of 0.5 mg dexamethasone every 6 hours or 0.75 mg every 8 hours for 2 days are commonly used. Failure to suppress second-day urinary 17-hydroxycorticoids to less than 50% of the baseline value or failure to suppress urinary free cortisol to below 55 nmol/24 hours supports a diagnosis of Cushing syndrome. Alternatively, a single-dose dexamethasone suppression test involves a baseline blood sample on the first day, followed by oral administration of 1 mg dexamethasone at midnight, with morning plasma cortisol measured the next day. Plasma cortisol levels that fail to suppress to less than 50% of the baseline value also indicate Cushing syndrome. A result showing cortisol suppression to below 50 nmol/L during the low-dose dexamethasone test effectively excludes the diagnosis.

Etiological Diagnosis

Identifying the underlying cause is crucial because treatment differs based on etiology. Understanding the clinical features of different types, interpreting imaging studies, and assessing the degree of elevation in serum and urinary cortisol, serum ACTH levels (elevated or within the normal range suggests ACTH-dependent types), and dexamethasone suppression test results typically provide an accurate etiological diagnosis. The differential diagnosis between Cushing disease and the slowly progressive form of ectopic ACTH syndrome can be particularly challenging. Ectopic ACTH syndrome often presents with more pronounced elevations in ACTH and cortisol levels, with poor suppression in the high-dose dexamethasone suppression test. In contrast, patients with Cushing disease typically respond to high-dose dexamethasone suppression despite lack of suppression in the low-dose test. If these measures fail to distinguish the two, inferior petrosal sinus sampling may be used to measure ACTH levels and compare the ratio between inferior petrosal sinus blood and peripheral venous blood. Thoracic abnormalities account for approximately 60% of ectopic ACTH syndrome cases, and thin-slice thoracic CT is often performed. If no thoracic lesions are found, abdominal imaging is recommended.

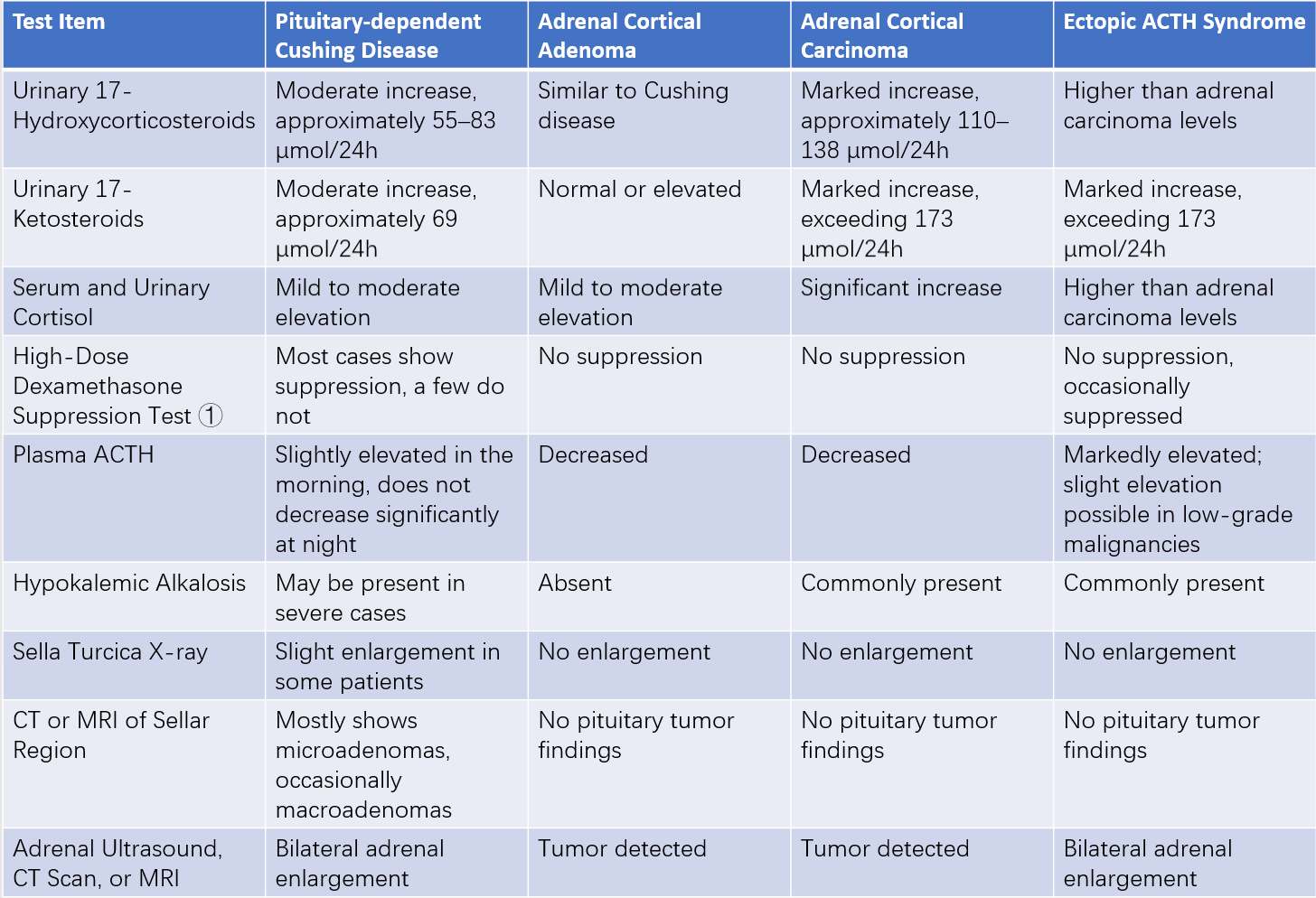

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of laboratory and imaging findings in different types of Cushing syndrome

Note: ① Each dose comprises 2 mg of dexamethasone. One dose is taken every 6 hours for 2 consecutive days. Suppression is indicated when 17-hydroxycorticosteroid levels or urinary free cortisol levels are reduced to less than 50% of baseline on the second day.

Differential Diagnosis

Obesity

Obese individuals may exhibit hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and abdominal striae (most of which are white, occasionally pale red but thinner). Urinary free cortisol levels are not elevated, and the diurnal rhythm of cortisol secretion remains intact.

Alcohol-Associated Pseudo-Cushing Syndrome

Individuals with chronic alcohol use and liver damage may present with clinical symptoms and elevated serum and urinary cortisol levels that are resistant to low-dose dexamethasone suppression. However, these biochemical abnormalities resolve within one week of alcohol cessation.

Depression

Patients with depression may exhibit elevated urinary free cortisol, 17-hydroxycorticosteroids, and 17-ketocorticosteroids, along with partial resistance to dexamethasone suppression. However, they do not display clinical features of Cushing syndrome.

Treatment

Treatment strategies depend on the underlying etiology.

Cushing Disease

Transsphenoidal Pituitary Surgery

Transsphenoidal surgery is the preferred treatment for Cushing disease. Microadenomas are identified in the majority of patients, and surgical removal usually results in remission. However, some patients experience disease recurrence post-surgery. The surgical success rate is lower in cases involving macroadenomas or invasive tumors. Transsphenoidal surgery is minimally invasive and has fewer complications. Temporary hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis insufficiency may develop postoperatively, requiring glucocorticoid supplementation until normal function is restored.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy serves as a second-line adjunctive treatment in patients with failed surgeries or disease recurrence. Fractionated external beam radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery achieves adequate control of hypercortisolism in approximately 50%–60% of patients within 3–5 years, with better outcomes in children. Hypopituitarism is the primary adverse effect of radiation, necessitating regular monitoring of pituitary function.

Bilateral Adrenalectomy

Bilateral adrenalectomy is an option for patients with refractory cases following transsphenoidal surgery or pituitary radiation, unclear ACTH sources, or pharmacologically uncontrollable hypercortisolism. This procedure rapidly reduces cortisol levels and improves clinical symptoms. Postoperatively, patients require lifelong replacement therapy with glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids due to permanent adrenal insufficiency. Ongoing surveillance with pituitary MRI and ACTH level monitoring is necessary because of the risk of developing Nelson's syndrome.

Medication Therapy

Targeted medications may be used as adjunctive therapy. ACTH-lowering medications, such as dopamine receptor agonists (e.g., cabergoline) and somatostatin receptor analogs (e.g., pasireotide), are effective in some patients with Cushing syndrome. For patients who do not respond satisfactorily to other treatments, adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors can be utilized.

Adrenal Cortical Adenoma

Surgical removal can achieve a complete cure. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic removal of unilateral tumors results in faster postoperative recovery. Most adenomas are unilateral. Postoperatively, prolonged replacement therapy with hydrocortisone (approximately 20–30 mg daily) or cortisone (approximately 25.0–37.5 mg daily) is typically required due to suppression of pituitary and contralateral adrenal function during prolonged hypercortisolemia. As adrenal function gradually recovers, the dose of cortisone can be progressively reduced. Most patients can taper off replacement therapy between 6 months to 1 year or even longer.

Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma

Early surgical intervention is strongly recommended. For cases where complete surgical removal is not feasible or metastasis is present, adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors are used to reduce adrenal hormone production.

Primary Pigmented Nodular Adrenocortical Disease (PPNAD) and ACTH-Independent Macronodular Adrenal Hyperplasia (AIMAH)

Bilateral adrenalectomy is performed, followed by lifelong hormone replacement therapy.

Ectopic ACTH Syndrome

Treatment should address the primary malignant tumor, using surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy, depending on the clinical situation. If a cure is achieved, symptoms of Cushing syndrome may resolve. If complete removal of the tumor is not possible, adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors are necessary.

Medications that Inhibit Adrenal Steroidogenesis

Mitotane (o,p’-DDD)

This drug induces atrophy, hemorrhage, and necrosis of cells in the adrenal zona fasciculata and zona reticularis and is primarily used for adrenal carcinoma. The initial dose ranges from 2–6 g per day, divided into 3–4 oral doses, with an increase to 8–10 g daily if necessary. Adverse effects may include gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. During therapy, glucocorticoid supplements are required to prevent adrenal insufficiency.

Metyrapone

This drug inhibits adrenal cortical 11β-hydroxylase and blocks cortisol biosynthesis. It is administered at a dose of 2–6 g daily, divided into 3–4 oral doses. Adverse effects may include loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting.

Aminoglutethimide

This medication inhibits the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, impairing glucocorticoid synthesis. It may be effective in cases of adrenal carcinoma that cannot be cured. The daily dose ranges from 0.75–1.0 g, divided into multiple doses.

Ketoconazole

This agent reduces corticosteroid synthesis. The initial dose is 1,000–1,200 mg daily, with maintenance doses of 600–800 mg daily. Severe liver damage may occur in a small number of patients.

Perioperative Management for Pituitary or Adrenal Surgery in Cushing Syndrome Patients

Once pituitary or adrenal lesions are surgically removed, cortisol secretion markedly decreases, posing a risk of acute adrenal insufficiency. Appropriate perioperative care is required. Prior to anesthesia, intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg is administered, followed by 100 mg every 6 hours. From the following day, the dosage is gradually reduced, transitioning to oral physiological maintenance doses over 5–7 days, depending on the clinical condition and postoperative adrenal function test results. Dosages and treatment duration are determined based on the underlying cause, postoperative clinical status, and adrenal function assessments.

Prognosis

With effective treatment, gradual improvement is typically observed over the following months. Symptoms such as central obesity may diminish, glycosuria disappears, menstrual cycles resume, and fertility may be restored. Psychological status often improves, and blood pressure decreases. However, in cases with long-standing disease accompanied by irreversible renal vascular damage, normalization of blood pressure may not be achievable. The efficacy of cancer treatment depends on early detection and whether complete surgical removal is possible. Early surgical removal of adenomas is associated with a favorable prognosis. The therapeutic outcomes of Cushing disease vary; regular follow-up is essential to monitor for recurrence or adrenal insufficiency. The gradual darkening of skin pigmentation may suggest the development of Nelson syndrome.