Obesity is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the body, resulting from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors, among others. It serves as a significant risk factor and pathological foundation for chronic non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and tumors. Obesity and its associated conditions not only severely impair the physical and mental health of affected individuals, reducing their quality of life, but may also shorten life expectancy.

Epidemiology

According to the Global Obesity Report, there were 988 million individuals with obesity worldwide in 2020, accounting for 14% of the global population. By 2035, the global number of individuals with obesity is projected to reach 2 billion, representing 24% of the population.

Classification

Obesity can be classified into two major categories based on its cause and pathogenesis: primary and secondary obesity. Primary obesity is not caused by specific diseases, medication use, or other identifiable factors and is the most common form of obesity. Secondary obesity results from specific pathological or physiological conditions such as Cushing's syndrome, primary hypothyroidism, and corticosteroid use.

Based on fat distribution, obesity can be categorized as central (abdominal) or peripheral (subcutaneous fat) obesity. Central obesity is characterized by fat accumulation predominantly in the abdominal region, increased visceral fat, waist enlargement, and an "apple-shaped" body type, which is more commonly observed in males. Peripheral obesity is characterized by fat accumulation in areas such as the hips and thighs, presenting a "pear-shaped" body type, which is more commonly observed in females.

Based on the presence of metabolic cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia), obesity can also be classified as metabolically healthy obesity and metabolically unhealthy obesity. Compared to metabolically healthy individuals with obesity, those with metabolically unhealthy obesity face a higher risk of obesity-related complications.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Primary obesity is generally caused by energy intake consistently exceeding energy expenditure. It results from the interaction of genetic, environmental, social, psychological, and other factors.

Genetic Factors

Obesity exhibits familial clustering, with the majority of primary obesity cases being caused by polygenic inheritance, resulting from the additive effects of multiple small-effect genes. Examples include the FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated gene) and MC4R (melanocortin 4 receptor gene). Some forms of obesity are caused by single-gene mutations, such as in genetic syndromes like Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome. Recently, specific single-gene mutations, such as those in LEP (leptin), LEPR (leptin receptor), POMC (pro-opiomelanocortin), PCSK1 (prohormone convertase 1), MC4R, and PPARG (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), have been identified as contributors to obesity.

The "thrifty gene hypothesis" is currently regarded as an important mechanism explaining obesity. It proposes that the human capacity to efficiently utilize energy during periods of food scarcity for survival is maladaptive in environments of food abundance, contributing to abdominal obesity and insulin resistance. Genes associated with susceptibility to abdominal obesity include beta-3 adrenergic receptor, hormone-sensitive lipase, PPARG, PCSK1, and IRS-1 (insulin receptor substrate-1).

Environmental Factors

Excess caloric intake and physical inactivity are the primary environmental factors driving the increasing prevalence of obesity. Dietary patterns also have an impact, as the increased consumption of high-sugar, high-fat foods, including animal-based products, processed foods, sugary beverages, and fried foods, significantly raises the risk of obesity. Other factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep disorders, and circadian rhythm disruption also elevate the risk of obesity.

Adverse intrauterine exposures early in life, such as abnormal metabolic environments, maternal malnutrition during fetal development, and exposure to electromagnetic fields, as well as low birth weight, may influence endocrine and metabolic systems during the fetal or early childhood stages, increasing the likelihood of obesity during childhood or adolescence. Environmental endocrine disruptors, such as phthalates, dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), can also lead to or exacerbate obesity by blocking hormone receptors or interfering with the normal transduction of hormone signals.

Social and Psychological Factors

Socioeconomic status affects dietary and exercise choices. Those facing economic hardship may opt for high-calorie foods more frequently. Psychological issues, such as depression and anxiety, are associated with dietary imbalances, and stress may enhance preferences for sugary and high-fat foods.

Pathophysiology

Energy Balance and Weight Regulation

Energy balance and weight regulation are complex physiological processes resulting from interactions between central and peripheral signals. These processes involve the central nervous system, liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and are regulated by both the nervous and endocrine systems.

The hypothalamus plays a central role in regulating energy balance. Within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, various neurons modulate appetite. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) stimulate appetite, while pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine-amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) suppress appetite. Signals influencing the hypothalamic appetite center include neural inputs (primarily via the vagus nerve, transmitting visceral information such as gastrointestinal distension), hormonal signals (e.g., leptin, insulin, and various gut peptides), and metabolic products (e.g., glucose). After integration, these signals transmit outputs via neurohumoral pathways to target organs, regulating processes such as gastric acid secretion, gastrointestinal motility, hormone release, and thermogenesis, thereby maintaining individual energy balance.

Key peripheral hormones involved in energy metabolism regulation include leptin, adiponectin, insulin, ghrelin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), galanin, growth hormone, thyroid hormones, and adrenaline. Dysregulation of neurohumoral pathways may lead to energy imbalance. When energy intake persistently exceeds energy expenditure, fat accumulation and weight gain result, contributing to the development of obesity.

Adipose Tissue and Adipocytes

The human body contains three types of adipose tissue: white, brown, and beige. White adipose tissue is the most common and is primarily responsible for energy storage. Brown adipose tissue facilitates energy expenditure. Beige adipose tissue, also known as brite (brown-in-white) fat, is intermediate between white and brown adipose tissue. While it stores energy in a resting state, it can generate heat and promote energy expenditure under cold exposure or specific stimuli. Sympathetic nervous system activation stimulates brown adipose tissue, triggering lipolysis and thermogenesis via β-adrenergic receptors.

Adipocytes are highly specialized cells that store and release energy and secrete various adipokines, hormones, or regulatory factors such as leptin, resistin, adiponectin, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), angiotensinogen, and free fatty acids (FFAs). These molecules play crucial roles in metabolism and maintaining homeostasis. In individuals with obesity, adipocyte hyperplasia (increased number) and hypertrophy (increased size) often occur, accompanied by adipose tissue inflammation, including infiltration of macrophages and other immune cells. This inflammation results in elevated secretion of adipokines, insulin resistance, and low-grade systemic inflammation (manifested by mild increases in markers such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-α).

Set-Point Elevation

The body weight set-point is a physiological mechanism that maintains weight stability through regulation of appetite and energy expenditure. When body weight deviates from this set-point, compensatory adjustments aim to restore balance. However, long-term consumption of a high-calorie, high-fat diet can lead to obesity and a sustained rise in the body weight set-point, resulting in its upward adjustment. Reversible weight gain typically involves adipocyte hypertrophy; when the cause of weight gain is removed, adipocytes shrink and body weight returns to baseline. Irreversible weight gain involves both adipocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy, making weight reduction more challenging.

Other Factors

Factors such as aging, inflammation, and gut microbiota dysbiosis are also closely associated with obesity. Aging leads to a reduction in metabolic rate, facilitating energy surplus and fat accumulation. Hormonal changes linked to aging, such as declining estrogen levels in perimenopausal women, further contribute to abdominal fat accumulation. There is a strong interrelationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance, creating a vicious cycle. Additionally, endotoxemia resulting from gut microbiota dysbiosis is an important contributor to inflammation and the development of obesity.

Clinical Manifestations

Obesity can occur at any age and in individuals of any gender. It is commonly associated with excessive food intake and/or insufficient physical activity and frequently has a familial predisposition.

Mild obesity is often asymptomatic, while moderate to severe obesity may lead to symptoms such as shortness of breath, joint pain, muscle soreness, as well as anxiety or depression. These individuals are at increased risk of obesity-related complications or comorbidities. Severe cases may involve psychological issues such as low self-esteem or depression. Individuals with obesity typically present with pronounced fat accumulation in areas such as the abdomen, hips, thighs, and upper arms.

Complications

Obesity serves as an underlying condition for multiple diseases and is often associated with conditions such as impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes, dyslipidemia, fatty liver disease, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. Additionally, obesity may lead to or coexist with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, stress urinary incontinence, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gallbladder diseases, hyperuricemia and gout, osteoarthritis, venous thrombosis, and impaired fertility (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome in women). It also increases the risk of certain cancers, such as breast and endometrial cancer in women and prostate, colon, and rectal cancer in men, while posing higher risks for complications during anesthesia or surgery.

Diagnosis

A thorough medical history is essential, including inquiries about personal diet, lifestyle habits, physical activity, disease duration, family history, medication history (e.g., drugs that contribute to obesity), psychological issues, or secondary causes of obesity such as Cushing’s syndrome and hypothyroidism. Evaluations of related complications and comorbidities, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, may be necessary.

The assessment of obesity involves determining the degree of obesity, body fat content, and fat distribution. Commonly used assessment methods include the following:

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI (kg/m2) = weight (kg) ÷ [height (m)]2.

Standards for adults are as follows:

- BMI of 18.5–23.9 kg/m2 is normal,

- BMI of 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 indicates overweight,

- BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m2 indicates obesity.

BMI does not provide an accurate description of fat distribution and cannot differentiate between fat and muscle mass, making it prone to misclassification, particularly for muscular individuals.

Body Weight (BW)

Ideal Body Weight (kg) = Height (cm) − 105 or [Height (cm) − 100] × 0.9 (for males) or × 0.85 (for females).

A weight within ±10% of the ideal body weight is considered normal. Exceeding the ideal weight by 10%–19.9% indicates overweight, and exceeding it by 20% or more indicates obesity.

Waist Circumference (WC)

The measurement is performed with the patient standing, feet separated by 25–30 cm for even weight distribution, at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the lower margin of the 12th rib. Central obesity is defined by a waist circumference of ≥90 cm in men and ≥85 cm in women. Waist circumference is the preferred parameter recommended by the WHO for evaluating central obesity.

Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR)

Hip circumference is measured at the widest point of the hips. According to the WHO, a WHR >0.9 in men and >0.85 in women indicates central obesity. However, individuals with similar WHR values may have significant weight differences, and the correlation of WHR with visceral fat accumulation is weaker compared to waist circumference.

Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR)

WHtR is calculated as the ratio of waist circumference to height. A WHtR greater than 0.5 reflects excessive abdominal fat accumulation.

Body Fat Percentage

This is the total fat content in the body expressed as a percentage. Ideal body fat percentages are typically 10%–20% for men and 20%–30% for women.

CT or MRI

These imaging techniques measure subcutaneous fat thickness or visceral fat volume and provide the most accurate assessment of fat distribution, though they are not used routinely in clinical practice.

Differential Diagnosis

Secondary obesity is diagnosed based on the clinical presentation and characteristic features observed through laboratory investigations for underlying conditions. Common causes include:

Cushing’s Syndrome

Central (truncal) obesity is often accompanied by features such as a "moon face" and "buffalo hump," with a substantial increase in visceral fat and relatively thin extremities. Blood cortisol levels are elevated or normal.

Hypothalamic Obesity

Fat accumulation is prominent in the face, neck, and trunk, with associated symptoms such as tender skin, thin finger tips, intellectual disability, hypogonadism, diabetes insipidus, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency. Imaging studies such as cranial CT or MRI and endocrine function tests aid in diagnosis.

Primary Hypothyroidism

This condition is commonly characterized by a significantly reduced basal metabolic rate and moderate weight gain, which may be accompanied by myxedema. Thyroid function tests provide diagnostic confirmation.

Laurence-Moon-Biedl Syndrome

This autosomal recessive disorder manifests in infancy and is characterized by obesity, intellectual disability, pigmentary retinopathy, polydactyly or syndactyly, and hypogonadism.

Prader-Willi Syndrome

This syndrome results from a deletion on chromosome 15q11.2-q13. Features include growth retardation, short stature, small hands and feet, and intellectual disability. Infants often experience feeding difficulties and delayed speech development, while increased appetite and overeating in childhood can lead to obesity. Other characteristics include a narrow forehead, almond-shaped eyes, upward slanting palpebral fissures, strabismus, a thin upper lip, dental anomalies, a small chin, and abnormal ear shape, along with hypogonadism and cryptorchidism in males.

Medications

Obesity may result from the use of certain medications such as antipsychotic drugs and glucocorticoids. A detailed medication history is important for differential diagnosis.

Treatment

The key to treating obesity lies in reducing caloric intake and increasing energy expenditure. Setting personalized weight-loss goals is critically important. A comprehensive approach that emphasizes behavioral therapies such as diet management and physical activity forms the cornerstone of treatment, while medications or surgery may be considered when necessary. For secondary obesity, treatment focuses on the underlying condition. Complications and comorbidities are managed accordingly.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications represent the most crucial approach to treating obesity. Health education helps patients and their families develop a proper understanding of obesity and its associated risks, fostering the adoption and long-term maintenance of a healthy lifestyle, including balanced nutrition and adequate exercise.

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional therapy forms the foundation of obesity treatment by limiting caloric intake so that energy consumption exceeds energy intake. The focus lies in reducing carbohydrate and fat intake while ensuring adequate provision of essential nutrients such as amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Special attention is given to sufficient protein intake to minimize protein loss associated with weight reduction.

The appropriate daily caloric intake should be calculated using the formula:

Total daily energy needs = ideal body weight (kg) × caloric requirement per kg of body weight (kcal/kg).

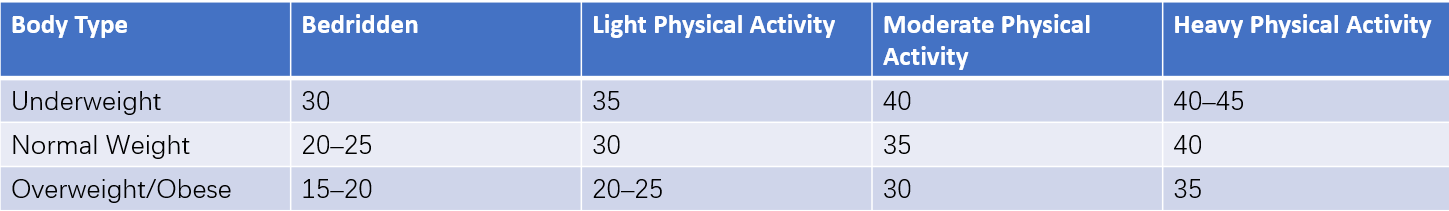

Table 1 Daily caloric intake recommendations for adults (Unit: kcal/kg)

In addition, proper nutrient distribution is important, with the following general recommendations: 20%–25% of total calories from protein, 25%–30% from fat, and 45%–60% from carbohydrates. Protein should primarily consist of high-quality sources (≥50%), such as eggs, dairy, meat, fish, and soy protein. Sufficient intake of fresh vegetables and fruits is emphasized, while consumption of high-fat or fried foods, sugary foods and beverages, heavily processed foods, and restaurant or takeaway meals is minimized.

Common dietary strategies for weight management include calorie-restricted diets (CRD), low-calorie diets (LCD), low-carbohydrate diets (LCD), high-protein diets (HPD), intermittent fasting, and time-restricted feeding (TRF).

Calorie-Restricted Diets (CRD) aim to limit energy intake while meeting basic nutritional needs with balanced nutrient distribution. Three methods are commonly used in CRD:

- Gradually reduce caloric intake by 30%–50% from baseline.

- Decrease daily caloric intake by 500 kcal.

- Limit daily caloric intake to 1,000–1,500 kcal.

This approach is suitable for individuals requiring weight control.

Low-Calorie Diets (LCD), also known as calorie-restricted diets, focus on reducing the intake of fats and carbohydrates while ensuring adequate intake of protein, vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber, and water. For adults, the daily caloric intake should not fall below 1,000 kcal. Very-low-calorie diets (VLCD) involve a daily intake of 400–800 kcal, primarily sourced from protein, with strict limitation of fat and carbohydrate intake. This approach is not recommended for pregnant or lactating women or adolescents in growth and development stages.

Low-Carbohydrate Diets (LCD) are characterized by carbohydrate intake contributing ≤40% of total energy, fat contributing ≥30%, and a relatively higher proportion of protein intake. Some regimens may restrict or leave total energy intake unrestricted. Very-low-carbohydrate diets aim for carbohydrates comprising ≤20% of total energy, with ketogenic diets being a specific subtype.

High-Protein Diets (HPD) involve protein intake accounting for 20%–30% of total calories or 1.5–2.0 g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily. This approach may help improve lipid abnormalities in simple obesity and is particularly suited for patients with uncomplicated obesity.

Intermittent Fasting, also known as periodic fasting, alternates between normal eating for five days per week and consuming only one-quarter of daily caloric needs on two nonconsecutive days. This method may assist with weight control and metabolic improvement but is not recommended for individuals prone to hypoglycemia, hypotension, or frailty. Prolonged use may lead to malnutrition or ketosis.

Time-Restricted Feeding (TRF) offers a more flexible approach by limiting food intake to a specified time window, with no or minimal caloric intake outside of this period. A common TRF pattern is the 16:8 schedule, where individuals fast for 16 hours each day and eat within an 8-hour window. This approach is generally more acceptable and sustainable for patients compared to other methods.

Exercise Interventions

Appropriate exercise interventions can reduce body weight, improve blood pressure, blood lipids, and insulin resistance, lower the risk of developing hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cancer, and decrease both all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Exercise is also associated with enhanced muscle mass and bone density, as well as reductions in anxiety and depression, contributing to improved mental health, cognitive function, and sleep quality.

Exercise type and intensity should align with the specific circumstances of each patient, with gradual progression being emphasized. For individuals with cardiovascular complications or impaired pulmonary function, careful consideration is required, and individualized exercise prescriptions should be developed based on their specific conditions. Patients with moderate to severe obesity often experience obesity-related diseases such as fatty liver, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. For these patients, the safety of physical activity must be prioritized during exercise. Those with concomitant obesity-related conditions who take medications may require guidance to appropriately time their medication intake in relation to exercise to avoid events such as exercise-induced hypoglycemia, hypotension, or worsening of fatty liver.

Pharmacological Treatment

The use of pharmacological treatment is indicated under the following conditions:

- Excessive appetite with persistent hunger before meals and large meal portions.

- Coexisting conditions such as hyperglycemia, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or fatty liver disease.

- Weight-bearing joint pain related to obesity.

- Obesity-related breathing difficulties or obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

For individuals with a BMI ≥24 kg/m2 and comorbidities outlined above, or those with a BMI ≥28 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities, who fail to achieve a 5% weight loss or continue to gain weight despite dietary control and increased physical activity over a 3–6 month period, pharmacological treatment may be considered.

However, weight-loss medications are contraindicated in certain situations, including:

- Children.

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women.

- Individuals experiencing severe adverse reactions to such medications.

- Patients with serious cardiac, liver, or kidney diseases.

- Patients with certain psychiatric disorders.

- Those taking medications that may interact negatively with weight-loss drugs.

Intestinal Lipase Inhibitors

Orlistat, an inhibitor of gastrointestinal lipase enzymes, reduces fat absorption. In the early stages of treatment, mild gastrointestinal side effects such as increased gas, frequent bowel movements, and steatorrhea may occur, and fat-soluble vitamin absorption may be impaired. Cases of severe liver injury have been reported, warranting caution. The recommended dose is 120 mg, three times a day, taken with meals.

Anti-Diabetic Medications with Weight-Loss Effects

GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as liraglutide and semaglutide, induce weight loss by suppressing appetite, delaying gastric emptying, and promoting the browning of white adipose tissue. These drugs have been approved for the treatment of obesity. Metformin, which enhances glucose uptake and increases insulin sensitivity, has some weight-loss effects but has not been approved for obesity management. Its primary side effects include gastrointestinal disturbances. In addition, dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as tirzepatide, have been approved for the treatment of obesity in adults.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is reserved for individuals with severe obesity who have failed to achieve weight loss and have serious complications. The most common procedure is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, accounting for over 95% of weight-loss surgeries. Such surgeries can significantly reduce cardiovascular mortality and overall mortality in individuals with severe obesity. However, surgical treatment carries risks of complications such as malnutrition, anemia, or gastrointestinal strictures, making it essential to strictly adhere to eligibility criteria. A thorough preoperative evaluation of the patient’s overall health, including targeted management of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiopulmonary dysfunction, is necessary.

Prevention

The occurrence of obesity is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. The modifiability of environmental factors offers opportunities for prevention. Efforts should focus on promoting public awareness and encouraging the adoption of healthy lifestyles. Early identification of individuals with a tendency toward obesity is important, and high-risk individuals should be provided personalized guidance. Preventive measures should begin in childhood, with particular emphasis on promoting health education among adolescents.