Dehydration refers to a condition of fluid volume deficiency caused by fluid loss. Based on the proportional loss and composition of water and electrolytes (primarily sodium, Na+), dehydration is classified into hypertonic dehydration, isotonic dehydration, and hypotonic dehydration.

Etiology

Hypertonic Dehydration

Inadequate Water Intake:

- Causes include coma, trauma, refusal to eat, difficulty swallowing, or lack of access to fresh water.

- Conditions such as brain injury or stroke may dull the thirst center or render osmoreceptors insensitive.

Excessive Water Loss:

- Renal Losses:

- Central or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma, hypercalcemia, and similar conditions.

- Osmotic diuresis caused by prolonged nasogastric feeding with high-protein liquid diets (nasogastric feeding syndrome).

- Use of hypertonic glucose solutions, mannitol, sorbitol, urea, or non-solute diuretics.

- Extrarenal Losses:

- Profuse sweating.

- Significant loss of hypotonic fluids during open treatment of burns.

- Increased pulmonary water loss due to conditions such as status asthmaticus, excessive hyperventilation, or tracheostomy, leading to a two- to three-fold rise in water loss.

- Intracellular Water Shift:

- Intense exercise or seizures may increase intracellular small-molecule substances, raising osmotic pressure and causing water to shift into cells.

Isotonic Dehydration

Gastrointestinal Losses: Emesis, diarrhea, gastrointestinal drainage, or intestinal obstruction leading to fluid loss.

Skin Losses: Exudative skin lesions such as extensive burns or exfoliative dermatitis.

Interstitial Fluid Sequestration: Drainage of inflammatory effusions from the thoracic or abdominal cavities, or frequent large-volume thoracentesis or paracentesis.

Hypotonic Dehydration

Excessive Water Replacement: Excessive water intake during hypertonic or isotonic dehydration.

Renal Losses:

- Excessive use of natriuretic diuretics such as thiazides or furosemide.

- Presence of large amounts of non-reabsorbable solutes (e.g., urea) in renal tubules, inhibiting sodium and water reabsorption.

- Conditions such as salt-losing nephritis, the polyuric phase of acute renal failure, renal tubular acidosis, and diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Adrenal insufficiency.

Clinical Manifestations

Hypertonic Dehydration

Mild Dehydration

Water loss exceeds sodium loss, resulting in reduced extracellular fluid volume and increased osmotic pressure. When water loss reaches 2% to 3% of body weight, activation of the thirst center induces thirst, stimulating the release of antidiuretic hormone to enhance water reabsorption, thereby reducing urine volume and increasing urine specific gravity. If polydipsia (increased water intake) is present, extracellular fluid volume depletion and osmolarity abnormalities may not occur; if thirst is impaired, hypertonic dehydration may develop.

Moderate Dehydration

When water loss reaches 4% to 6% of body weight, there is increased aldosterone secretion and plasma osmotic pressure, leading to severe thirst, difficulty swallowing, and hoarseness. Effective circulatory volume is reduced, causing tachycardia. Additional symptoms include dry skin with decreased elasticity, accompanied by fatigue, dizziness, and irritability due to intracellular dehydration.

Severe Dehydration

When water loss reaches 7% to 14% of body weight, severe water loss from brain cells causes neurological symptoms such as mania, delirium, disorientation, hallucinations, syncope, and dehydration fever. A water loss exceeding 15% of body weight may result in hyperosmolar coma, hypovolemic shock, anuria, acute renal failure, and a high risk of mortality.

Isotonic Dehydration and Hypotonic Dehydration

In isotonic dehydration, reduced effective circulating blood volume and renal perfusion manifest as oliguria and thirst. In severe cases, blood pressure declines, but osmotic pressure remains essentially normal.

Hypotonic dehydration is characterized by early-onset reduced effective circulating blood volume and oliguria, but without thirst. Severe cases may lead to intracellular hypotonicity and cellular edema. Clinically, sodium deficiency is evaluated and categorized into mild, moderate, and severe levels.

Mild Dehydration

A sodium deficit of approximately 8.5 mmol per kilogram of body weight (plasma sodium around 130 mmol/L) may be associated with systolic blood pressure above 100 mmHg. Symptoms include fatigue, weakness, reduced urine output, thirst, and dizziness, with very low or undetectable urine sodium levels.

Moderate Dehydration

A sodium deficit of 8.5 to 12.0 mmol per kilogram of body weight (plasma sodium around 120 mmol/L) may result in systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg, along with nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps, extremity numbness, collapsed veins, and orthostatic hypotension. Urine sodium may be undetectable.

Severe Dehydration

A sodium deficit of 12.8 to 21.0 mmol per kilogram of body weight (plasma sodium around 110 mmol/L) may result in systolic blood pressure below 80 mmHg, accompanied by symptoms such as cold extremities, hypothermia, rapid thready pulse, and shock. Neurological symptoms such as stupor or coma may develop, with life-threatening consequences.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The type and severity of dehydration can be inferred based on the medical history (e.g., insufficient sodium intake, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, profuse sweating) and confirmed through necessary laboratory tests. Hyperosmolar dehydration is often linked to conditions such as fever or diabetes insipidus, while vomiting and diarrhea are more commonly associated with hypotonic or isotonic dehydration.

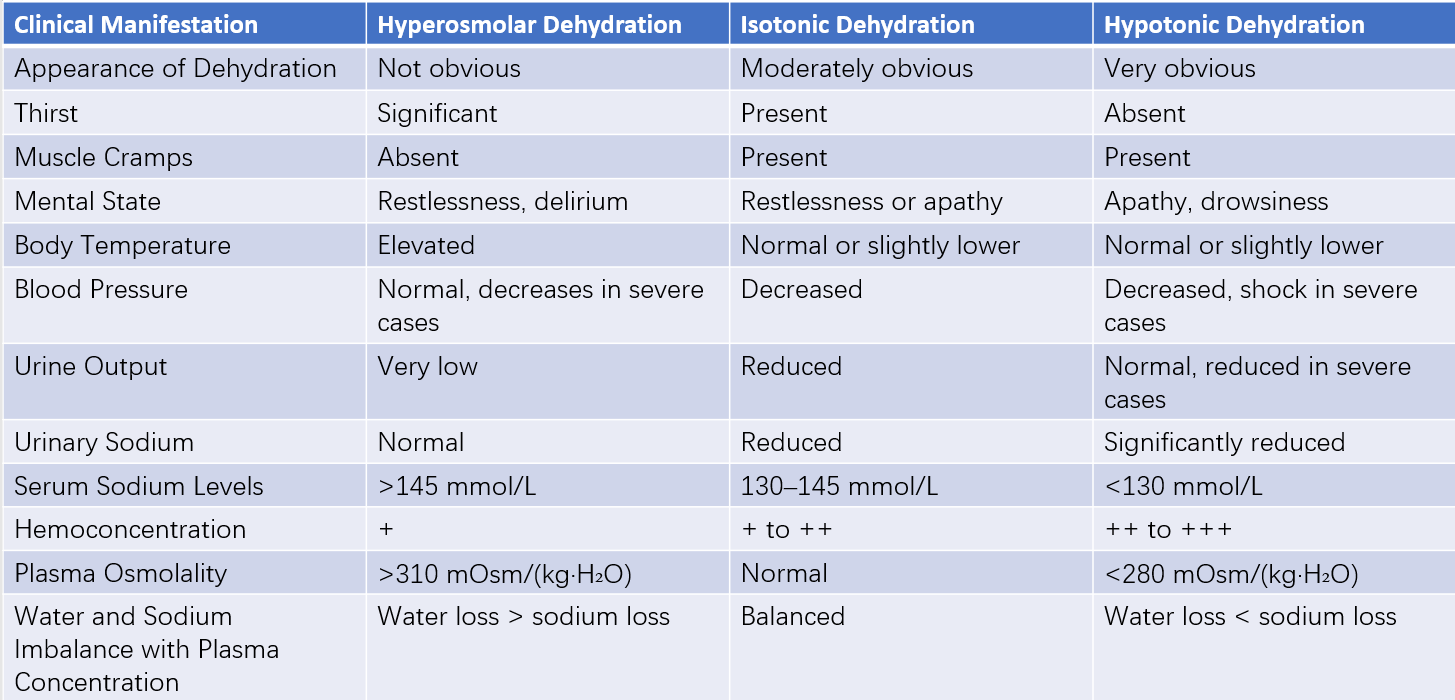

Table 1 Comparison of three types of dehydration

Note: The above typically refers to moderate or severe dehydration.

Prevention and Treatment

Active treatment of the underlying condition is emphasized, along with avoiding inappropriate dehydration, the use of diuretics, or high-protein enteral feeding. The type and severity of dehydration, along with the individual's condition, guide the formulation of a rehydration plan.

Total Rehydration Volume

The total rehydration volume consists of two components: fluid that has already been lost and fluid that continues to be lost.

Previously Lost Volume

Four estimation methods are available:

- Estimation Based on Severity of Dehydration:

- Mild dehydration corresponds to 2%–3% of body weight; moderate dehydration corresponds to 4%–6% (approximately 2,400–3,600 mL); severe dehydration corresponds to 7%–14%, with losses exceeding 15% in severe cases.

- Estimation Based on Initial Body Weight:

- 30–40 mL/kg of body weight.

- Estimation Based on Serum Sodium Levels:

- Applicable to hyperosmolar dehydration, with the following three formulas:

- Fluid loss = total normal body fluid - current total body fluid. Total normal body fluid = initial body weight × 0.6. Current total body fluid = (normal serum sodium ÷ measured serum sodium) × total normal body fluid.

- Fluid loss = (measured serum sodium - normal serum sodium) × current body weight × 0.6 ÷ normal serum sodium.

- Fluid loss = current body weight × K × (measured serum sodium - normal serum sodium), where the coefficient K is 4 for males and 3 for females.

- Estimation Based on Hematocrit:

- Applicable for estimating fluid loss in hypotonic dehydration. The formula is:

- Rehydration volume (mL) = [(measured hematocrit - normal hematocrit) ÷ normal hematocrit] × body weight (kg) × 200. Normal hematocrit values are 0.48 for males and 0.42 for females.

Ongoing Loss Volume

This refers to fluid losses that occur after the patient seeks medical attention and includes physiological requirements (approximately 1,500 mL/day) and pathological losses (e.g., profuse sweating, pulmonary exhalation, vomiting).

These formulas provide only a rough estimation of fluid loss. Adjustments should be made based on the patient's actual condition during clinical practice.

Types of Rehydration

Sodium and water losses occur in all types of dehydration (hyperosmolar, isotonic, and hypotonic), albeit to varying degrees, necessitating both sodium and water replacement. Typically, rehydration fluids for hyperosmolar dehydration contain about 1/3 sodium-containing solutions, isotonic dehydration fluids about 1/2, and hypotonic dehydration fluids about 2/3.

Hyperosmolar Dehydration

The primary focus is on water replacement, with supplementary sodium. Oral or enteral rehydration directly replenishes water, while intravenous rehydration may involve 5% glucose solution, 5% glucose saline solution, or 0.9% saline solution. Appropriate potassium and alkaline solutions may also be added.

Isotonic Dehydration

The primary approach is isotonic fluid replacement, with 0.9% saline solution being the first choice. Prolonged use, however, may cause hyperchloremic acidosis. To better match the normal sodium-to-chloride ratio of extracellular fluid (7:5), a combination of 1,000 mL of 0.9% saline + 500 mL of 5% glucose solution + 100 mL of 5% sodium bicarbonate solution may be used.

Hypotonic Dehydration

The primary focus is on hypertonic fluid replacement. The 5% glucose solution in the isotonic formula can be replaced by 250 mL of 10% glucose solution, and additional 3%–5% saline solution may be administered if necessary. Rehydration volume can be calculated based on the sodium content, with 1 g of sodium chloride equating to approximately 17 mmol of sodium ions. Hypertonic solutions, however, must be administered slowly, with the increase in serum sodium typically limited to 0.5 mmol/L per hour. The sodium supplementation volume can be calculated using the following formulas:

- Sodium supplementation volume = (125 mmol/L - measured serum sodium) × 0.6 × body weight (kg).

- Sodium supplementation volume = (142 mmol/L - measured serum sodium) × 0.2 × body weight (kg).

Here, 0.6 × body weight (kg) represents the total body fluid volume, and 0.2 × body weight (kg) represents the extracellular fluid volume. Typically, 1/3 to 1/2 of the sodium supplementation volume is administered initially, with biochemical indicators rechecked to determine the subsequent treatment plan.

Rehydration Methods

Rehydration Route

Oral or enteral rehydration is preferred wherever feasible. Moderate to severe dehydration or unmet needs are addressed through intravenous rehydration.

Rehydration Rate

The rate of rehydration begins relatively fast and slows down thereafter. For severe cases, 1/3 to 1/2 of the total rehydration volume is administered within the first 4–8 hours, with the remainder infused over 24–28 hours. The exact rate of rehydration depends on the patient’s age, cardiac, pulmonary, and renal functions, as well as the severity of the condition.

Precautions

The fluid intake and output over a 24-hour period should be recorded.

Body weight, blood pressure, pulse, serum electrolytes, and acid-base balance require close monitoring.

In cases requiring rapid and large-volume fluid replacement, enteral rehydration through nasogastric feeding is preferred. For intravenous supplementation, central venous pressure monitoring (<120 mmH2O) is recommended.

Potassium supplementation is suitable when urine output exceeds 30 mL/h, with a typical concentration of 3 g/L. When urine output exceeds 500 mL/day, the daily potassium supplementation can reach 10–12 g.

Acid-base imbalance should be corrected as necessary.