Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone mass and the disruption of bone microarchitecture, leading to increased bone fragility. It can be classified into primary and secondary osteoporosis based on etiology. Primary osteoporosis includes postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMOP, Type I), senile osteoporosis (Type II), and idiopathic osteoporosis (in juveniles). PMOP typically occurs within 5–10 years after menopause in women, senile osteoporosis generally manifests after the age of 70, and idiopathic osteoporosis predominantly affects adolescents with an unclear cause. Secondary osteoporosis refers to cases resulting from diseases, medications, or other identifiable factors affecting bone metabolism. This chapter focuses on primary osteoporosis.

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

Osteoporosis is a complex disease resulting from the interplay of genetic and environmental factors. To maintain normal physiological function, bones require a continuous, spatially and temporally coupled process of bone resorption and bone formation, known as bone remodeling. Bone remodeling is a dynamic and ongoing process: osteoclasts degrade localized bone tissue during resorption, creating resorption pits, which are subsequently filled with new bone formed by osteoblasts.

Prior to adulthood, bone formation exceeds bone resorption, culminating in peak bone mass (PBM).

During adulthood, bone remodeling achieves a balance that maintains bone mass.

With age, bone resorption outpaces bone formation, leading to bone loss.

Bone remodeling is regulated by numerous factors, including endocrine hormones, cytokines, and several signaling pathways. Any factor disrupting the balance between bone resorption and bone formation can result in reduced bone mass, osteoporosis, or even fractures.

Factors Affecting Bone Resorption

Sex Hormone Deficiency

A decline in estrogen levels weakens the inhibition of osteoclast activity, enhancing bone resorption. Earlier onset of menopause leads to more severe estrogen deficiency and greater bone loss.

Inflammatory Mediators

Aging and estrogen deficiency lead to chronic low-grade activation of the immune system, creating a pro-inflammatory state. Inflammatory mediators induce the expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL), stimulating osteoclast activity and resulting in bone loss.

Vitamin D Deficiency and Increased Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) Secretion

Aging and declining renal function reduce the production of active form vitamin D [1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3)], leading to diminished intestinal calcium absorption. PTH secretion increases compensatorily, accelerating bone turnover and bone loss.

Other Factors

Age-related declines in the growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor axis, sarcopenia, and reduced physical activity decrease mechanical loading on bones, contributing to increased bone resorption.

Factors Affecting Bone Formation

Reduced Peak Bone Mass (PBM)

PBM, typically achieved around age 30, is a critical determinant of bone mass during adulthood. PBM is primarily influenced by genetic factors but is also associated with race, family history of fragility fractures, growth and development, nutrition, and lifestyle.

Decline in Bone Remodeling Functions

Osteoblast dysfunction or reduced activity leads to insufficient bone formation and consequent bone loss. Impaired bone remodeling is a key mechanism underlying senile osteoporosis.

Decreased Bone Quality

Bone quality is largely genetically determined and encompasses factors such as bone geometry, degree of mineralization, accumulation of microdamage, and the physico-chemical and biological properties of bone mineral and matrix. Reduced bone quality increases bone fragility and fracture risk.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for osteoporosis can be divided into uncontrollable and controllable categories.

Uncontrollable Risk Factors

These include race, aging, female menopause, and family history of fragility fractures.

Controllable Risk Factors

Modifiable risk factors include unhealthy lifestyle choices, such as reduced physical activity, limited exposure to sunlight, excessive consumption of alcohol or caffeine-containing beverages, nutritional imbalances, and low body weight. Additionally, many diseases and medications can lead to secondary osteoporosis (details provided in the section on differential diagnosis).

Clinical Manifestations

Osteoporosis often lacks obvious clinical manifestations in its early stages. However, as the disease progresses with ongoing bone loss and microarchitectural disruptions, patients may develop bone pain, spinal deformities, and even osteoporotic fractures.

Bone Pain

Bone pain of varying degrees and locations is the most common symptom. It is typically unrelated to joint redness or deformity and is often accompanied by fatigue in the lower back and legs, cramping in the lower extremities, and difficulty or restriction in activities such as bending, squatting, turning over, or walking.

Height Loss and Spinal Deformities

Severe osteoporosis resulting in vertebral compression fractures may lead to a reduction in height or kyphotic spinal deformities. A height reduction ≥4 cm compared to peak adult height, or ≥2 cm compared to the prior year, warrants strong suspicion of osteoporosis. Vertebral fractures can also cause thoracic deformities, abdominal compression, and impaired cardiopulmonary function.

Fractures

Fragility fractures can occur due to minimal trauma, such as forceful coughing or laughing. Common fracture sites include vertebrae (thoracic and lumbar spine), the proximal humerus, distal radius, ribs, hips (femoral neck and intertrochanteric region), and the ankles. The risk of subsequent fractures significantly increases following an initial osteoporotic fracture.

Complications

Patients with kyphosis and thoracic deformities may experience chest tightness, difficulty breathing, and decreased cardiopulmonary function. These conditions are often accompanied by cardiovascular diseases and pulmonary infections. Post-fracture, patients may experience reduced or lost independence in daily activities along with restricted mobility. Prolonged bed rest can exacerbate bone loss and significantly hinder fracture healing. Psychological impacts, including fear, anxiety, depression, and reduced self-confidence, are also common.

Laboratory and Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Examinations

General Tests

Routine tests include blood count, urine analysis, liver and kidney function tests, as well as serum calcium, serum phosphate, serum alkaline phosphatase, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25-(OH)D], and PTH levels. Urine calcium, urine phosphate, and urine creatinine levels are also assessed.

Bone Turnover Markers

Bone turnover markers are intermediate products or enzymes involved in the bone remodeling process and are divided into markers of bone formation and bone resorption. Serum procollagen type I N-propeptide (P1NP) and serum C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) are recommended for their high sensitivity in reflecting bone formation and resorption, respectively.

Additional Testing for Differential Diagnosis

Depending on the clinical context, assessments such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, sex hormones, thyroid function, urinary free cortisol, blood gas analysis, urine Bence-Jones protein, and serum/urine light chains may be conducted.

Auxiliary Examinations

Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

BMD is the amount of bone mass per unit volume or area. Various methods exist for measuring BMD, with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and quantitative computed tomography (QCT) being the most commonly used in clinical and research settings. DXA is currently considered the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis both domestically and internationally.

Other Imaging Techniques

Imaging studies, such as vertebral X-rays, CT, MRI, radionuclide bone scans, bone marrow aspiration, or bone biopsy, may be considered to evaluate vertebral fractures or distinguish primary from secondary osteoporosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Clues

Osteoporosis is often suspected in elderly individuals or postmenopausal women presenting with unexplained chronic lower back pain, reduced height, or spinal deformities. Risk factors include advanced age, immobilization, low body weight, prolonged bed rest, or long-term glucocorticoid use.

Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis is based on clinical history, symptoms, physical signs, and necessary auxiliary tests, with secondary causes of osteoporosis excluded. The diagnosis is primarily determined by BMD measurements and/or the presence of fragility fractures.

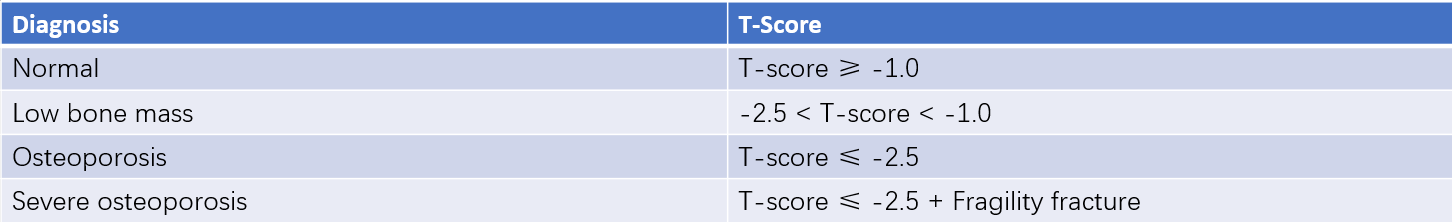

Diagnosis Based on BMD

For postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older, the WHO diagnostic criteria are applied. BMD results obtained through DXA are converted into T-scores for diagnosis:

T-score = (measured BMD - peak bone mass of normal young adults of the same race and gender) / standard deviation of peak bone mass of normal young adults of the same race and gender.

For children, premenopausal women, and men under 50 years of age, Z-scores are recommended to assess bone density:

Z-score = (measured BMD - average BMD of age-, race-, and gender-matched peers) / standard deviation of the BMD in age-, race-, and gender-matched peers.

A Z-score ≤ -2.0 is considered "below the expected range for age" or indicative of low bone mass.

Table 1 Classification criteria based on DXA-determined bone mineral density (BMD)

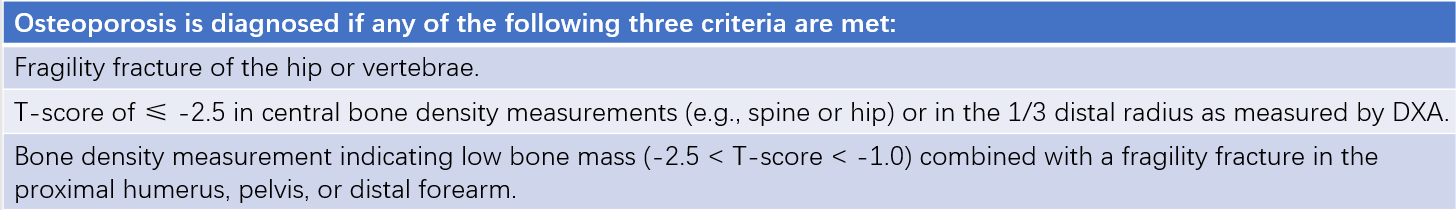

Diagnosis Based on Fragility Fractures

Diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis include fragility fractures.

Table 2 Diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis

Differential Diagnosis

Before diagnosing primary osteoporosis (OP), secondary causes of osteoporosis need to be excluded, as certain diseases and medications are known to lead to secondary OP.

Common Diseases

These include:

- Endocrine Disorders: Hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing's syndrome, hypogonadism, diabetes mellitus (both Type 1 and Type 2), hypopituitarism, premature ovarian failure (defined as menopause before age 40), and anorexia nervosa.

- Hematologic Disorders: Multiple myeloma, leukemia, lymphoma, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, and hemophilia.

- Rheumatologic and Autoimmune Disorders: Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriasis.

- Gastrointestinal Disorders: Inflammatory bowel disease, malabsorption syndromes, celiac disease, and postoperative conditions following weight-loss surgery.

- Neuromuscular Disorders: Epilepsy, muscular atrophy, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke.

- Other Diseases: Chronic metabolic acidosis, end-stage renal disease, post-organ transplantation bone disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Common Medications

Many medications can disrupt bone metabolism and lead to secondary OP, including glucocorticoids, proton pump inhibitors, aromatase inhibitors, chemotherapy agents, heparin, antiepileptic drugs, excessive thyroid hormones, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs.

Prevention and Management

Osteoporosis prevention should span the entire lifespan and should not be limited to adult or elderly stages. The main approaches to OP prevention and management include foundational measures, pharmacological interventions, and rehabilitation therapies.

Basic Treatments

Lifestyle Modifications

Strategies include maintaining a nutritious and balanced diet, ensuring adequate sunlight exposure, engaging in regular physical exercise, avoiding smoking, limiting alcohol intake, minimizing or discontinuing the use of medications that affect bone metabolism, and taking precautions to prevent falls.

Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation

Calcium

Appropriate calcium supplementation is recommended for all osteoporosis patients to ensure a total daily elemental calcium intake of 800–1,200 mg. Dietary calcium provides approximately 400 mg daily, so an additional 500–600 mg per day from supplements is necessary. Common calcium supplements include calcium carbonate, calcium gluconate, and calcium citrate.

Vitamin D

In addition to adequate sunlight exposure, oral supplementation with regular vitamin D2 or D3 may be required. For individuals with malabsorption or poor adherence, injectable forms of vitamin D can be administered intramuscularly. A serum 25-(OH)D level of ≥30 ng/mL is recommended for osteoporosis patients, though monitoring is necessary to prevent hypercalcemia caused by excessively high levels.

Anti-Osteoporosis Medications

Effective pharmacologic treatments for osteoporosis help to improve bone density and reduce the risk of fractures. These medications fall into three categories based on their mechanisms: bone resorption inhibitors, bone formation stimulators, and others with alternative mechanisms.

Bone Resorption Inhibitors

This group includes bisphosphonates, RANKL monoclonal antibodies, calcitonin, estrogens, and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs).

Bisphosphonates

These are the most widely used anti-osteoporosis drugs in clinical practice. As stable analogs of pyrophosphate, bisphosphonates contain a P-C-P group, exhibit high affinity for hydroxyapatite in bone tissue, and specifically target active bone remodeling sites to inhibit osteoclast activity and bone resorption. Common bisphosphonate medications include:

- Alendronate Sodium: Tablets containing 10 mg are taken orally once daily, or 70 mg tablets once weekly. Combination tablets containing 70 mg alendronate sodium and either 2,800 IU or 5,600 IU vitamin D3 are also available for weekly use.

- Zoledronic Acid: This intravenous medication (5 mg) is administered via infusion once a year.

- Other Bisphosphonates: Risedronate sodium, ibandronate sodium, and minodronate.

Bisphosphonates are generally well tolerated. However, potential adverse effects include gastrointestinal disturbances, transient flu-like symptoms such as fever and bone pain, renal impairment, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and atypical femoral fractures. Monitoring of treatment efficacy, alongside serum calcium, phosphate, and bone turnover markers, is advised during therapy.

RANKL Monoclonal Antibodies

RANKL interacts with receptors (RANK) on osteoclast precursors and mature osteoclasts. The interaction between RANKL and RANK promotes osteoclast differentiation, maturation, and activation, initiating the bone resorption process. Denosumab is a fully human IgG2 monoclonal antibody that binds with high specificity and affinity to RANKL, preventing its interaction with its receptor RANK. This action inhibits osteoclast formation and activation, reduces bone resorption, and increases bone mineral density. The recommended dosage is 60 mg administered subcutaneously once every six months. Denosumab is generally well-tolerated, but long-term use may slightly increase the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw or atypical femoral fractures. It is also important to ensure that denosumab therapy is not discontinued without transitioning to bisphosphonates or other medications afterward, as stopping denosumab can lead to bone density loss.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin is a calcium-regulating hormone that inhibits osteoclast activity, reduces osteoclast numbers, and increases bone mass. It is also effective in alleviating bone pain and treating hypercalcemia. Currently, salmon calcitonin and eel calcitonin analogs are commonly used in clinical practice. The primary formulations include:

- Salmon calcitonin: Available as a nasal spray at a dose of 200U, used once daily or every other day. Salmon calcitonin injections are administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly at a dose of 50U daily.

- Elcatonin injections: Administered intramuscularly at a dose of 20U once weekly or 10U twice weekly.

Long-term use of salmon calcitonin is associated with a slightly increased risk of malignancy, and it is generally recommended that the duration of continuous use not exceed three months.

Estrogen

Hormone therapy for menopause can prevent accelerated bone turnover and bone loss associated with menopause and can reduce the risk of fractures. It is suitable for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMOP). It is recommended for initiation in women before the age of 60 or within 10 years of menopause to alleviate menopause-related symptoms and provide cardiovascular protection. Common formulations and doses include:

- Conjugated estrogen: A typical dose ranges from 0.3 to 0.625 mg/day.

- Estradiol valerate: 0.5 to 2 mg/day.

- 17β-estradiol: 1 to 2 mg/day.

- Tibolone: 1.25 to 2.5 mg/day.

- Estradiol transdermal patches: 0.05 to 0.1 mg/day.

Transdermal patches can bypass first-pass metabolism in the liver, reducing effects on coagulation activity, and are advantageous for women with impaired liver function or at risk for thromboembolism. Regular gynecological and breast examinations are necessary during estrogen therapy, and it is contraindicated in women with uterine or breast cancer, severe liver or renal dysfunction, unexplained vaginal bleeding, or endometrial hyperplasia.

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs)

SERMs bind to estrogen receptors (ERs) and induce conformational changes, resulting in tissue-specific estrogen agonist or antagonist effects. For example, raloxifene acts as an estrogen agonist on bone, inhibiting bone resorption and increasing bone density, while exerting estrogen antagonist effects on breast and uterine tissues, thereby avoiding stimulation of these tissues.

Bone Formation Stimulators

Parathyroid hormone analogs (PTHa) can intermittently promote bone formation and increase bone mass when administered in low doses. Teriparatide, a recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34 fragment), is an approved PTHa in clinical use. Teriparatide is typically administered as a 20 μg subcutaneous injection once daily, with a maximum treatment duration of 24 months.

Drugs with Other Mechanisms

Active Vitamin D and Its Analogs

Available active vitamin D products and analogs approved include alfacalcidol (1α-hydroxyvitamin D), calcitriol [1,25-(OH)2D3], and eldecalcitol. These drugs are particularly suitable for elderly individuals, patients with renal insufficiency, or those with reduced or deficient 1α-hydroxylase activity. Concomitant use of high-dose calcium supplements during treatment is not advised, and regular monitoring of serum calcium and urinary calcium levels is required.

Vitamin K

Menatetrenone, a homolog of vitamin K2, serves as a coenzyme for carboxylase and plays an important role in the formation of γ-carboxyglutamate. This compound is essential for the physiological function of osteocalcin and contributes to increased bone mass.

Treatment of Osteoporotic Fractures

The treatment principles for osteoporotic fractures include realignment, fixation, functional rehabilitation exercises, and anti-osteoporosis therapy.

Prevention

Public health education can improve awareness of osteoporosis, promote regular physical activity, and ensure adequate calcium intake. Early identification of at-risk individuals is essential for implementing primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive measures to reduce the risk of osteoporosis and related fractures.