Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease primarily characterized by erosive, symmetric polyarthritis. The exact pathogenesis remains unclear. The fundamental pathological changes include chronic synovial inflammation, formation of pannus, and progressive destruction of articular cartilage and bone, eventually leading to joint deformities and functional loss. RA is one of the major causes of workforce disability and physical impairment. Early diagnosis and early treatment are crucial for disease management. RA has a global distribution and can occur at any age, with a peak incidence between the ages of 35 and 50. The prevalence in females is 2–3 times higher than in males.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of RA are complex. The disease arises from a combination of genetic predisposition, infections, environmental factors, and autoimmune responses leading to immune-mediated damage and repair.

Genetic Susceptibility

Epidemiological studies indicate a strong association between RA and genetic factors. Family studies reveal that first-degree relatives of RA probands have an 11% probability of developing RA. Numerous studies have identified mutations in the HLA-DRB1 alleles as being correlated with RA development.

Environmental Factors

Although no direct infectious agent causing RA has been confirmed, certain pathogens, such as bacteria, mycoplasma, and viruses, may activate T cells, B cells, and other immune cells, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies, thereby affecting the onset and progression of RA. Components of pathogens may also trigger autoimmune responses via molecular mimicry. In addition, cigarette smoking has been shown to significantly increase the risk of developing RA.

Immune Dysregulation

Immune dysregulation represents a primary mechanism in RA development. Activated CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) expressing MHC class II molecules infiltrate the synovial membrane. Certain components of synovial tissue or endogenous substances may serve as autoantigens presented by APCs to activate CD4+ T cells, triggering specific immune responses that contribute to joint inflammation. In addition, activated B cells, macrophages, and synovial fibroblasts function as sources of autoantibodies and play crucial roles in the inflammatory processes of RA synovitis.

Pathology

The primary pathological change in RA is synovitis. In the acute phase, synovitis is characterized by exudation and cellular infiltration. Small blood vessels in the synovium exhibit dilation, endothelial cells become swollen, intercellular gaps widen, and stromal edema with neutrophil infiltration is observed. In the chronic phase, the synovium thickens, forming numerous villous projections extending into the joint cavity or invading the articular cartilage and subchondral bone. These villous structures, also known as pannus, demonstrate strong destructive properties and serve as the pathological basis for joint damage.

Microscopically, pannus tissue shows hyperplasia of synovial cells, increasing from the normal 1–3 layers to 5–10 layers or more. These hyperplastic cells primarily consist of macrophage-like type A cells and fibroblast-like type B cells. The subsynovial layer contains diffuse or nodularly aggregated lymphocytes, resembling lymphoid follicles. The majority of these lymphocytes are CD4+ T cells, followed by B cells and plasma cells. Newly formed blood vessels and activated fibroblast-like cells, as well as the subsequent formation of fibrous tissue, are also observed.

RA not only affects synovial joints but can also involve extra-articular tissues and organs, with vasculitis being a characteristic pathological manifestation. RA-related vasculitis may involve medium and small arteries and/or veins, displaying intimal hyperplasia, lymphocyte infiltration within the vascular wall, and fibrinoid necrosis. This leads to vessel wall thickening, luminal narrowing, or occlusion. Rheumatoid nodules represent a typical feature of vasculitis. Histologically, the nodules consist of fibrinoid necrotic tissue at the center, surrounded by rings of infiltrating epithelioid cells, with an outer layer of granulation tissue.

Clinical Manifestations

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) often presents with an insidious onset, characterized predominantly by symmetric polyarthritis involving the hands, wrists, and feet bilaterally. Symptoms include joint swelling and pain, accompanied by morning stiffness. Systemic symptoms such as fatigue, low-grade fever, muscle aches, and unintentional weight loss may be present. In rare cases, an acute onset of RA occurs, with typical joint symptoms developing within a few days. The clinical manifestations of RA show individual variability.

Joint-related Manifestations

Morning Stiffness

Morning stiffness refers to the sensation of joint stiffness and immobility, most prominent upon waking and alleviating with movement. It typically lasts for more than 30 minutes and is often considered a marker of disease activity, although it is a subjective symptom. Morning stiffness is observed in various types of arthritis but is most pronounced in RA.

Joint Swelling

Joint swelling is primarily caused by synovial hyperplasia, synovial effusion, and edema of the periarticular soft tissues. It often occurs symmetrically and is typically accompanied by joint pain. Commonly affected joints include the wrists, metacarpophalangeal joints, and proximal interphalangeal joints, followed by the toes, knees, ankles, elbows, and shoulders.

Joint Pain and Tenderness

These symptoms are among the earliest signs of RA. The localization of pain and tenderness usually corresponds to swollen joints, displaying a symmetric and persistent pattern. Tenderness is often associated with painful joints.

Joint Deformities

Joint deformities are observed in later stages of the disease. Muscle atrophy and spasms around the joints exacerbate deformities. Common joint deformities include subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joints, ulnar deviation of the fingers, swan-neck deformity, boutonniere deformity, wrist and elbow ankylosis.

Specific Joints

Shoulder and Hip Joints

Swelling is difficult to detect due to the surrounding soft tissues, such as tendons. Common symptoms include localized pain and restricted movement. Hip involvement often manifests as pain in the buttocks or lower back.

Temporomandibular Joint

Patients may experience worsened pain during activities such as speaking or chewing. Severe cases may lead to restricted mouth-opening.

Cervical Spine

Some patients develop cervical spine involvement, especially if disease control has been inadequate over a long period. Symptoms include neck pain, restricted movement, and, in severe cases, atlantoaxial subluxation (C1–C2), which may lead to spinal cord compression.

Joint Dysfunction

Joint swelling, pain, and structural damage contribute to impaired joint mobility. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classifies the impact of RA on lifestyle into four grades:

- Grade I: Normal daily activities and all types of work remain unaffected.

- Grade II: General daily activities and some work tasks are possible, but participation in other activities is restricted.

- Grade III: General daily activities are possible, but engagement in work or other activities is limited.

- Grade IV: Both self-care and work-related tasks are significantly restricted.

Extra-articular Manifestations

Rheumatoid Nodules

Rheumatoid nodules represent the most common extra-articular manifestation, occurring in 30–40% of patients, often during periods of active disease. These are more common in males, particularly those with a history of heavy smoking. Nodules can develop anywhere but are typically found in pressure-prone areas, such as extensor surfaces of the forearms, beneath the ulnar olecranon, around the Achilles tendon, or in bursae. Nodules vary in size, from millimeters to centimeters in diameter, are firm, non-tender, and symmetrically distributed. Rheumatoid nodules in internal organs such as the heart, lungs, pleura, and eyes also suggest active disease.

Skin Vasculitis

Skin vasculitis is uncommon, with an incidence below 10%, and is most often observed in patients with long-standing, RF-positive RA with active disease. Manifestations range from petechiae, purpura, digital gangrene, infarction, and livedo reticularis to severe large ulcerations. Aggressive treatment with immunosuppressants is often required.

Cardiac Involvement

Pericarditis is the most frequent manifestation, particularly in RF-positive patients and those with rheumatoid nodules. Fewer than 10% of patients present with clinical symptoms, although nearly half may be identified through echocardiographic examination.

Pulmonary Involvement

Male patients are more frequently affected, and pulmonary involvement may occasionally be the initial presentation of RA.

Interstitial Lung Disease

This is the most common type of pulmonary involvement and affects approximately 30% of RA patients. Symptoms include exertional dyspnea and pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary function tests and high-resolution CT scans are helpful for early diagnosis.

Pleuritis

Pleuritis affects around 10% of patients and is characterized by unilateral or bilateral small pleural effusions, though massive effusions occur occasionally. The fluid is exudative in nature.

Nodular Changes

Multiple or solitary pulmonary nodules may represent rheumatoid nodules in the lungs, sometimes liquefying into cavities. Patients with pneumoconiosis and RA may develop numerous large pulmonary nodules, known as Caplan syndrome or rheumatoid pneumoconiosis.

Ocular Manifestations

Most commonly, secondary Sjögren’s syndrome leads to dry eye symptoms, which may include dry mouth and lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis often requires tests in oral and ophthalmologic clinics, as well as autoantibody evaluations. In severe cases, scleritis may occur, potentially causing scleral ulceration and perforation, leading to visual impairment. The pathological basis is scleral vasculitis, often indicative of active disease.

Neurological System

Neurological complications in RA are primarily due to nerve compression, such as carpal tunnel syndrome from median nerve compression at the wrist. Rheumatoid vasculitis may also cause symptoms like hand and foot numbness or mononeuritis multiplex, which reflects disease activity and necessitates prompt treatment. Cervical spine involvement at C1–C2 may lead to spinal cord complications.

Hematological System

Anemia is the most common hematological manifestation, and its severity correlates with the degree of joint inflammation. Anemia often improves with inflammation control. Active RA is also associated with thrombocytosis, proportional to disease activity, which typically normalizes upon disease remission. Felty syndrome, consisting of splenomegaly and neutropenia, may co-occur with anemia and thrombocytopenia. Patients with Felty syndrome often present with significant extra-articular symptoms such as lower limb ulcers, rheumatoid nodules, fever, fatigue, appetite loss, and weight loss, even when joint involvement is inactive.

Renal Involvement

Renal involvement in RA is rare but may manifest as mild membranous nephropathy, glomerulonephritis, renal small-vessel vasculitis, or renal amyloidosis. Drug-induced renal damage, particularly from long-term NSAID use, should be investigated if renal issues develop.

Laboratory and Other Auxiliary Examinations

Hematological Changes

Mild to moderate anemia, typically normocytic and normochromic, is common and correlates with disease activity. Platelet counts may increase during active disease phases, while white blood cell counts and differentiation are generally normal. Immunoglobulin levels are elevated, and serum complement levels are usually normal or slightly increased.

Inflammatory Markers

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are often elevated and serve as primary indicators of disease activity. These markers may return to normal during remission.

Autoantibodies

Rheumatoid Factor (RF)

RF is a class of autoantibodies targeting antigenic epitopes on the Fc fragment of IgG. It includes IgM, IgG, and IgA isotypes, with IgM RF being the most routinely tested. RF is positive in 75–80% of RA patients but lacks specificity; it can also occur in chronic infections, other autoimmune diseases, and in 1–5% of healthy individuals. A negative RF result does not exclude RA diagnosis.

Anti-citrullinated Protein Antibodies (ACPA)

ACPA refers to a group of antibodies targeting autoantigens with citrullinated epitopes. This group includes anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody, anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin (MCV) antibody, anti-perinuclear factor (APF) antibody, anti-keratin antibody (AKA), and anti-filaggrin antibody (AFA). Among these, anti-CCP antibodies demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity, with approximately 75% of RA patients testing positive. These antibodies have a specificity of 93–98%, are detectable in the early stages of the disease, and are associated with disease prognosis. Approximately 15% of RA patients test negative for both RF and ACPA, a condition referred to as seronegative RA.

Synovial Fluid

In healthy individuals, the volume of synovial fluid in joint cavities does not exceed 3–5 mL. During joint inflammation, synovial fluid volume increases. In RA, synovial fluid appears pale yellow, transparent, and viscous, with white blood cell counts significantly elevated to 5,000–50,000 × 10⁶/L, approximately two-thirds of which are polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Synovial fluid analysis can confirm joint inflammation and help differentiate between infectious arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis, such as gout and pseudogout, though it does not definitively diagnose RA.

Imaging Studies

X-ray

X-ray imaging of both hands, wrists, and other affected joints is essential for diagnosing RA, staging joint lesions, and monitoring disease progression. Early findings include periarticular soft tissue swelling and periarticular osteopenia (stage I). Subsequently, joint space narrowing may be observed (stage II), followed by erosive changes resembling moth-eaten patterns on joint surfaces (stage III). In the advanced stages, joint subluxation, as well as fibrous or bony ankylosis, may develop (stage IV).

MRI

MRI is particularly valuable for early diagnosis. It can detect soft tissue abnormalities, synovitis, edema, hyperplasia, joint effusions, and bone marrow edema, offering greater sensitivity compared to X-ray.

Ultrasound

High-frequency ultrasound can clearly visualize joint cavities, synovium, bursae, joint effusions, and articular cartilage thickness. It not only assesses synovial hyperplasia but also reflects the degree of inflammatory activity in the synovium through blood flow signals. Ultrasound can also be used to guide joint aspiration and treatment.

Arthroscopy and Needle Biopsy

Arthroscopy has diagnostic and therapeutic value in RA, while needle biopsy is a simple and minimally invasive procedure.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis

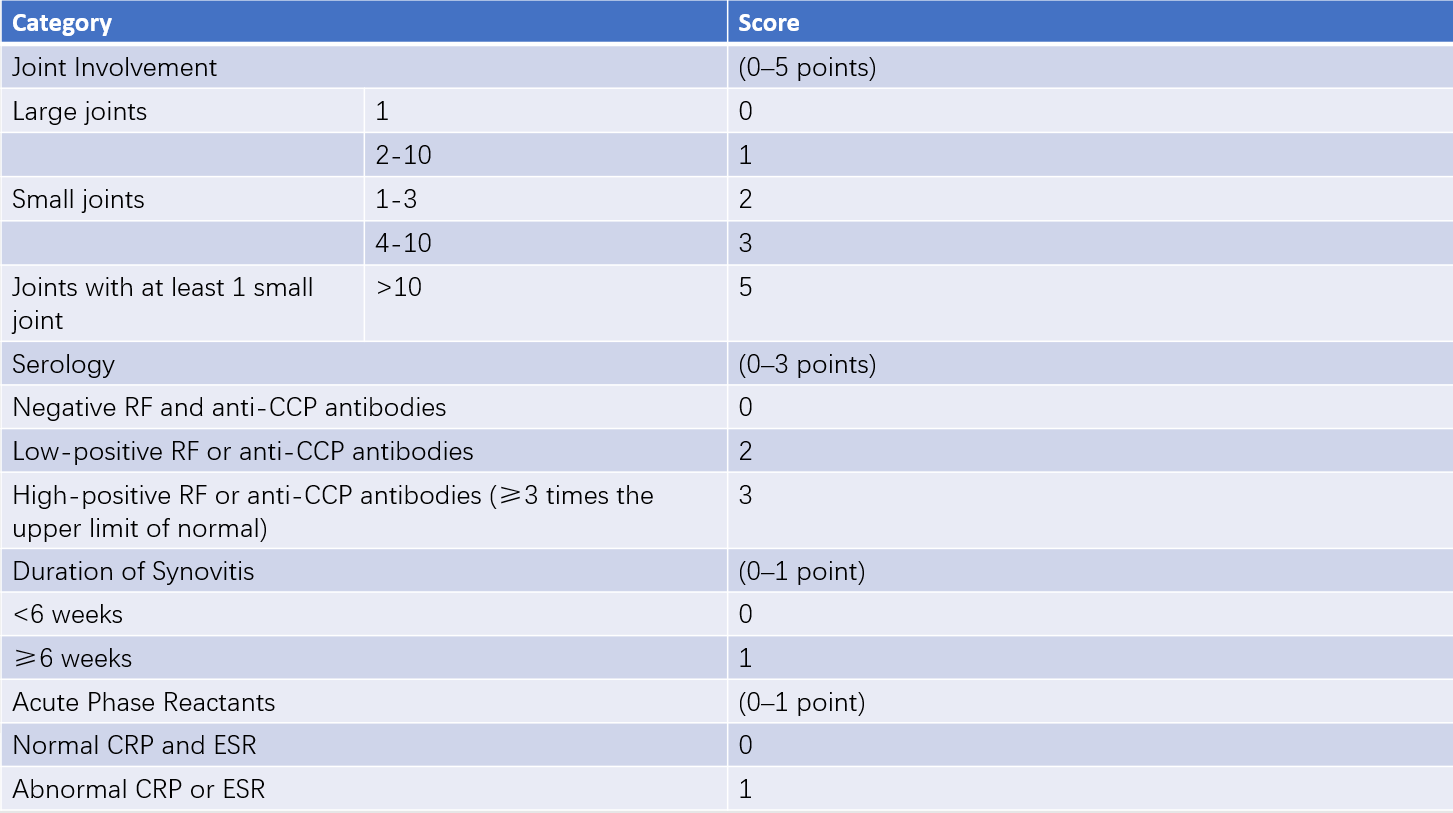

The clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is primarily based on symptoms and signs of chronic arthritis, along with laboratory and imaging studies. There is currently no definitive diagnostic criterion for RA, but classification criteria combined with clinical presentation can aid in diagnosis. Widely used diagnostic tools include the 2010 RA classification criteria and scoring system developed jointly by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). These criteria evaluate four components: joint involvement, serological markers, duration of synovitis, and acute-phase reactants. A total score of 6 points or higher allows classification as RA.

Table 1 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA

Notes:

Affected joints refer to those that are swollen or tender.

Small joints include the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, 2nd–5th metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, and wrist joints, excluding the first carpometacarpal (CMC-1) joint, first MTP joint, and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.

Large joints refer to the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle joints.

Differential Diagnosis

RA must be differentiated from the following diseases:

Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA is more common in middle-aged and elderly individuals, predominantly affecting weight-bearing joints like the knees, ankles, and spine, often with asymmetrical involvement. Affected joints may show swelling and effusion. Pain typically worsens with activity and improves with rest. Hand OA frequently involves the distal interphalangeal joints (DIP), and diagnosis is supported by the presence of Heberden's nodes (at DIP joints) and Bouchard's nodes (at proximal interphalangeal joints, PIP). Knee joint involvement may exhibit a sensation of friction. RF and ACPA are generally negative. X-rays demonstrate marginal osteophytes or bony spurs, narrowed joint spaces, and no joint destruction.

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)

AS predominantly occurs in young males and mainly affects the sacroiliac joints and the spinal joints. When peripheral joints are involved, especially as the initial presentation in the knees, ankles, or hips, RA needs to be excluded. AS typically features asymmetric inflammation of large lower limb joints and rarely involves the hands. X-rays often show sacroiliac joint bone erosion and joint fusion. A family history is common, and over 90% of patients are positive for HLA-B27, while RF tests are negative.

Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA)

PsA usually develops years after the onset of psoriasis, and joint involvement is commonly asymmetric. A minority of patients may exhibit symmetric polyarthritis resembling RA, but PsA more often involves the distal interphalangeal joints and presents with features such as enthesitis and dactylitis. Sacroiliitis and spinal inflammation may also occur. RF is usually negative.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Some SLE patients present with swollen and painful finger joints as the initial symptom, along with positive RF, elevated ESR, and CRP levels, which may lead to misdiagnosis as RA. However, joint manifestations in SLE are typically non-destructive. Extra-articular symptoms such as butterfly rash, hair loss, skin lesions, and proteinuria are prominent. Positive findings for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody further support the diagnosis of SLE.

Other Forms of Arthritis

Numerous other types of arthritis exist, each characterized by the underlying disease. A thorough understanding of these conditions aids in accurate differentiation.

Disease Assessment

Assessing disease activity in RA is critical for selecting treatment strategies and evaluating treatment success. Current evaluation methods incorporate composite measures of disease activity, including the duration of morning stiffness, the number of painful and swollen joints, inflammatory markers (e.g., ESR, CRP), and assessments by both physicians and patients regarding the severity and activity of the disease. Tools such as the Disease Activity Score for 28 joints (DAS28) are commonly used to evaluate disease activity. Prognostic factors, including disease duration, levels of physical disability (e.g., assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire [HAQ] score), extra-articular manifestations, positivity for autoantibodies, and X-ray evidence of early bone damage, should also be considered.

Treatment

Currently, there is no cure for RA. Treatment strategies should adhere to principles of early, targeted, and individualized intervention, with close monitoring of disease progression and timely adjustments to therapy. The ultimate goal of treatment is to reduce disability. Treatment primarily aims to achieve clinical remission or low disease activity. Clinical remission is defined as the absence of significant signs and symptoms of inflammatory activity. Optimal treatment plans require collaboration between clinicians and patients.

Treatment measures for RA primarily include general therapy, pharmacological therapy, and surgical interventions, among which pharmacological therapy plays the most significant role.

General Therapy

This includes patient education, rest, joint immobilization during the acute phase, functional joint exercises during the recovery phase, and physical therapy. Bed rest is generally appropriate only during the acute phase, for patients with fever or internal organ involvement.

Pharmacological Therapy

Commonly used medications for RA can be categorized into six groups: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biological DMARDs, targeted DMARDs, glucocorticoids (GC), and herbal medicines. Initial treatment must involve the use of at least one DMARD.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs exhibit analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects and are often used to relieve joint symptoms. However, their impact on disease control is limited and hence should be combined with DMARDs. NSAIDs may increase the risk of cardiovascular events, so medication choices must be individualized, and concurrent use of two or more NSAIDs should be avoided.

Conventional DMARDs

This category includes methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine. These drugs generally act slowly, requiring 1–3 months to take effect. While they lack significant analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, they are effective in slowing and controlling disease progression. Once RA is diagnosed, early initiation of conventional DMARDs is recommended. Drug selection and treatment regimens depend on the activity, severity, and progression of the disease. DMARDs can be used as monotherapy or in combination. Methotrexate is the preferred first-line treatment. Each DMARD has distinct mechanisms of action and side effects, requiring careful monitoring during use.

Biological DMARDs

The development of biological DMARDs over the past three decades represents a revolutionary advancement in RA treatment. These therapies are primarily targeted at cytokines and cell surface molecules that play pivotal roles in RA pathogenesis. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors were the first approved biologics for RA treatment, followed by agents targeting interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), CD20 monoclonal antibodies, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) fusion proteins. TNF-α inhibitors and IL-6 inhibitors are the most widely used biologics today. If initial treatment with conventional DMARDs fails to achieve the desired outcomes or if poor prognostic factors are present, the use of biological agents should be considered. To enhance efficacy and reduce side effects, biological agents are often used in combination with methotrexate. TNF-α inhibitors carry an increased risk of reactivation of latent infections (e.g., tuberculosis, hepatitis virus infection), so screening for these infections should be conducted prior to initiating treatment. Common side effects of biologics include injection site and infusion reactions, along with an elevated risk of infections such as respiratory infections and herpes zoster virus infections. Prolonged use of certain biologics may increase the risk of malignancies, which should be ruled out before initiating treatment.

Targeted DMARDs

Targeted DMARDs are small-molecule synthetics that selectively inhibit Janus kinase (JAK) pathways, blocking key inflammatory pathways involved in RA pathogenesis. These drugs act quickly and have clear clinical efficacy, making them an important component of RA treatment. Current JAK inhibitors in clinical practice include tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. For RA patients with inadequate responses to conventional DMARDs, JAK inhibitors may be added to the treatment regimen. Common adverse effects include leukopenia, liver function impairment, and an increased risk of infections such as viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and herpes simplex virus infections. Additionally, JAK inhibitors may elevate the risk of cardiovascular events and thromboembolism. In patients with high cardiovascular risk, JAK inhibitors require caution.

Glucocorticoids (GC)

Glucocorticoids have potent anti-inflammatory effects and can rapidly relieve joint swelling, pain, and systemic inflammation. They are often used as "bridge therapy" to swiftly control active disease until conventional DMARDs take effect, after which GC doses can be tapered and discontinued. Treatment with glucocorticoids adheres to the principle of low doses and short courses. Glucocorticoids must be used in combination with DMARDs. For patients with extra-articular manifestations involving major organs such as the heart, lungs, eyes, or nervous system—particularly those with secondary vasculitis—medium-to-high doses of glucocorticoids may be required. Intra-articular GC injections can be employed to manage inflammation in individual joints, though frequent joint aspirations increase the risks of infection and steroid-induced crystalline arthritis; generally, no more than three injections are recommended within a year. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation are recommended during GC use to prevent osteoporosis.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical options include joint replacement and synovectomy. Joint replacement is typically performed for late-stage deformities involving loss of joint function. Synovectomy may offer temporary symptom relief, though recurrence is possible if synovial hyperplasia reoccurs, necessitating concurrent DMARDs therapy.

Prognosis

The prognosis of RA depends on disease duration, severity, and whether treatment targets are achieved. Advances in the understanding of RA, optimized use of conventional DMARDs, and the advent of biological and targeted DMARDs have significantly improved outcomes. With early diagnosis and standardized treatment, more than 80% of RA patients can achieve remission.