Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by pathogenic autoantibodies and immune complex formation, which mediate damage to organs and tissues. Clinically, it often presents with multi-system involvement, with various autoantibodies—primarily antinuclear antibodies—detected in the serum. The prevalence of SLE varies across populations, with a global average prevalence of 12–39 per 100,000 people. In Northern Europe, the prevalence is approximately 40 per 100,000, while in Black populations, the prevalence is about 100 per 100,000.

Etiology

Genetic Factors

Epidemiological and Familial Studies

Data suggest that first-degree relatives of SLE patients are eight times more likely to develop SLE compared to individuals from families without SLE. Identical twins have a 5–10-fold higher concordance rate for SLE compared to fraternal twins. SLE patients' families often include relatives with other connective tissue diseases.

Susceptibility Genes

SLE has been established as a polygenic disease. Studies have identified associations with C2 or C4 deficiencies in the HLA class III region and with abnormal frequencies of DR2 and DR3 in the HLA class II region. It has been hypothesized that interactions among multiple genes under certain environmental conditions alter immune tolerance, leading to disease development. The onset of SLE involves the cumulative effects of numerous susceptibility gene abnormalities. However, known SLE-related genes explain only about 15% of its heritability.

Environmental Factors

Ultraviolet (UV) Light

UV light induces apoptosis in skin epithelial cells, exposing novel antigens that act as autoantigens.

Medications and Chemical Agents

Certain drugs reduce DNA methylation levels, triggering drug-induced lupus.

Viruses

Viruses such as cytomegalovirus and SARS-CoV-2 can also trigger disease onset.

Estrogen

The prevalence of SLE is significantly higher in females than in males, with a female-to-male ratio of 9:1 prior to menopause and 3:1 in children and the elderly.

Pathogenesis and Immune Abnormalities

The pathogenesis of SLE is highly complex and remains incompletely understood. Current evidence suggests that external antigens (e.g., pathogens, medications) activate B cells. In genetically predisposed individuals, weakened immune tolerance allows B cells to react with external antigens that mimic self-tissue components via cross-reactivity. These B cells present antigens to T cells, leading to T cell activation. Activated T cells stimulate B cells to produce large quantities of various autoantibodies, resulting in extensive tissue damage.

Pathogenic Autoantibodies

Pathogenic autoantibodies in SLE have the following characteristics:

- Predominantly IgG, with high affinity for self-antigens. For instance, anti-DNA antibodies directly bind to renal tissues, causing glomerular damage.

- Anti-platelet and anti-red blood cell antibodies cause platelet destruction and red blood cell hemolysis, leading to clinical manifestations such as thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia.

- Anti-SSA antibodies cross the placenta and affect the fetal heart, resulting in congenital heart block in newborns.

- Antiphospholipid antibodies lead to antiphospholipid syndrome, which is associated with thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and recurrent spontaneous abortions.

- Anti-ribosomal antibodies are associated with neuropsychiatric lupus.

Pathogenic Immune Complexes

SLE is an immune complex disease. Immune complexes (ICs) are formed by the binding of autoantibodies to corresponding self-antigens. ICs can deposit in tissues, causing tissue damage. The increase in ICs in this disease may be attributed to:

- Abnormal mechanisms for IC clearance.

- Excessive IC formation (due to large amounts of antibodies).

- Inappropriate IC size, making it difficult for ICs to be phagocytosed or excreted.

T Cell and NK Cell Dysfunction

Dysfunction of CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells in SLE patients results in the inability to suppress CD4+ T cells. Under CD4+ T cell stimulation, B cells remain persistently activated and produce autoantibodies. Abnormal T cell function generates a constant emergence of neoantigens, perpetuating autoimmunity.

Pathology

The primary pathological changes in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are inflammatory responses and vascular abnormalities, which may occur in any organ of the body. In small- to medium-sized vessels, the deposition of immune complexes (ICs) or direct antibody-mediated attack leads to inflammation and necrosis of the vessel walls. Secondary thrombosis further narrows the vascular lumen, causing localized tissue ischemia and functional impairment. The characteristic pathological changes in affected organs include:

- Hematoxylin bodies: Resembling eosinophilic inclusion bodies, these form from degenerated nuclei damaged by autoantibodies.

- "Onion-skin" lesions: Marked concentric fibrosis around small arteries, most prominently in the central arteries of the spleen, or connective tissues of heart valves undergoing repeated fibrinoid degeneration resulting in growths.

Similar pathological changes may also occur in the pericardium, myocardium, lungs, and nervous system. Renal involvement in SLE, specifically lupus nephritis, has distinct pathology outlined elsewhere.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical symptoms are diverse, and early presentations are often nonspecific.

General Symptoms

Most patients in the active phase of the disease experience fever, often low- to moderate-grade. Fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, myalgia, and weight loss may also occur.

Skin and Mucosal Symptoms

Skin rashes appear in 80% of patients during the course of the disease. These include malar rashes (butterfly-shaped erythema on the cheeks), discoid erythema, erythema on the fingers, palms, and periungual areas, ischemia of the fingertips, and rashes on the face and trunk. The butterfly-shaped malar rash across the nasal bridge and bilateral cheeks is most characteristic. SLE-related rashes are usually non-pruritic. Painless oral and nasal mucosal ulcers, as well as alopecia (diffuse or patchy), are common and often indicate disease activity.

Serositis

More than half of patients in the acute phase develop polyserositis, including bilateral small-to-moderate pleural effusion and small-to-moderate pericardial effusion. In some cases, pleural and pericardial effusions arise due to hypoalbuminemia caused by nephrotic syndrome in lupus nephritis or due to SLE-related cardiomyopathy or severe pulmonary hypertension. These effusions in such contexts do not signify lupus serositis and must be carefully distinguished during clinical assessments of lupus activity.

Muscle and Joint Symptoms

Arthralgia is one of the most common symptoms, often involving finger, wrist, and knee joints, although significant redness and swelling are uncommon. Symmetric polyarthritis is frequently observed. Approximately 10% of patients develop Jaccoud’s arthropathy due to periarticular tendon damage, characterized by reversible, non-erosive subluxation of joints, often preserving normal joint function. Radiographic findings typically show no joint destruction. Myalgia and muscle weakness may occur, with myositis present in 5%–10% of cases. A small proportion of patients develop femoral head necrosis during their disease course, which remains unclear whether it stems from SLE itself or is an adverse reaction to glucocorticoids.

Renal Involvement

Clinical renal involvement occurs in 27.9%–70% of SLE cases. Among Chinese patients, only 25.8% present with renal involvement as an initial feature. Common manifestations include proteinuria, hematuria, urinary casts, edema, hypertension, and, in severe cases, renal failure. Smooth muscle involvement may lead to ureteral dilation and hydronephrosis. Further details are provided in the section on lupus nephritis.

Cardiovascular Manifestations

Pericarditis is common, presenting as fibrinous or exudative pericarditis, though cardiac tamponade is rare. Libman-Sacks endocarditis (nonbacterial verrucous endocarditis) may occur, characterized by valvular vegetations. Unlike infectious endocarditis, these vegetations commonly appear on the ventricular side of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve and do not alter the properties of cardiac murmurs. Libman-Sacks endocarditis is typically asymptomatic, but it can cause embolic events or lead to secondary infectious endocarditis. Myocardial damage is observed in approximately 10% of patients, presenting as dyspnea, precordial discomfort, arrhythmias, or, in severe cases, heart failure that can result in death. Coronary artery involvement may manifest as angina and electrocardiographic ST-T changes or even acute myocardial infarction. Pathogenesis includes coronary arteritis, arterial thrombosis associated with antiphospholipid antibodies, and accelerated atherosclerosis due to prolonged glucocorticoid use.

Pulmonary Manifestations

SLE-induced interstitial lung disease primarily presents as acute or subacute ground-glass changes in early phases and fibrosis in later phases. Symptoms include exertional dyspnea, dry cough, and hypoxemia. Pulmonary function tests often demonstrate reduced diffusion capacity. About 2% of patients develop diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), a life-threatening condition with a mortality rate exceeding 50%. The diagnosis of DAH is supported by finding hemosiderin-laden macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or lung biopsy specimens, or by observing blood-stained lavage fluid. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is not uncommon in SLE and serves as a poor prognostic factor. Mechanisms include pulmonary vasculitis, dysregulation of pulmonary vascular tone, thromboemboli, and widespread interstitial lung involvement. Progressive dry cough and post-exertional dyspnea are characteristic symptoms. Echocardiography and right heart catheterization aid in diagnosis of PAH.

Neurological Manifestations

Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE), also known as lupus encephalopathy, affects both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Central nervous system involvement includes epilepsy, lupus headache, cerebrovascular disorders, aseptic meningitis, demyelinating syndromes, movement disorders, myelopathy, acute confusional states, anxiety, cognitive decline, mood disorders, and psychosis. Peripheral nervous system involvement may manifest as Guillain-Barré syndrome, autonomic neuropathy, mononeuropathy, myasthenia gravis, cranial neuropathy, plexopathy, or polyneuropathy. The pathological basis of NPSLE includes microthrombosis due to localized cerebral vasculitis, small emboli from vegetations on Libman-Sacks heart valves, autoantibodies targeting neural cells, or the coexistence of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Lumbar punctures for cerebrospinal fluid analysis and imaging studies like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide diagnostic assistance for NPSLE.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Gastrointestinal symptoms may include loss of appetite, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, with some patients presenting these symptoms as initial manifestations. Early hepatic injury is associated with a poor prognosis. A small proportion of patients may develop acute abdomen conditions, such as pancreatitis, intestinal necrosis, or intestinal obstruction, which are often related to SLE activity. Gastrointestinal symptoms are linked to vasculitis affecting the intestinal wall and mesenteric vessels. Protein-losing enteropathy and hepatic abnormalities may also occur in SLE. Following early glucocorticoid therapy, these symptoms often improve rapidly.

Hematological Manifestations

In active SLE, decreases in hemoglobin, white blood cell counts, and/or platelet counts are common. Approximately 10% of cases involve Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia. Thrombocytopenia is associated with the presence of antiplatelet antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, and impaired maturation of bone marrow megakaryocytes. Some patients may exhibit painless mild to moderate lymphadenopathy, while a small number present with splenomegaly.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS)

Approximately one-third of SLE patients have positive antiphospholipid antibodies, with a smaller portion meeting diagnostic criteria for APS. The clinical manifestations of APS include arterial and/or venous thrombosis, pathological pregnancy complications, and thrombocytopenia, along with persistent positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies. Antiphospholipid antibodies may be detected in the serum of SLE patients without fulfilling the clinical criteria sufficient for an APS diagnosis.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Approximately 30% of SLE patients exhibit secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, characterized by impaired salivary and lacrimal gland function.

Ocular Manifestations

Around 15% of SLE patients develop fundus abnormalities such as retinal hemorrhages, retinal exudates, and optic disc edema. These conditions are attributed to retinal vasculitis. Vasculitis may also involve the optic nerve, both of which impair vision and can lead to blindness within days in severe cases. With early treatment, vision can often be restored in most patients.

Laboratory and Other Auxiliary Examinations

General Tests

Abnormal findings may appear in routine blood and urine tests, liver and kidney function tests, and imaging studies, depending on the system involved. Patients with lupus encephalopathy often exhibit elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure and protein levels, although cell counts, chloride levels, and glucose concentrations are usually normal.

Autoantibodies

A variety of autoantibodies can be detected in the serum of patients, serving as diagnostic markers for SLE, indicators of disease activity, or predictors of certain clinical subtypes. Common autoantibodies include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antiphospholipid antibodies, and anti-organ-specific antibodies.

Antinuclear Antibody Spectrum

Common autoantibodies associated with SLE include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies, and anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies.

ANA

This is found in nearly all SLE patients; however, due to its low specificity, a positive ANA result alone cannot distinguish SLE from other connective tissue diseases.

Anti-dsDNA Antibodies

These are specific diagnostic markers for SLE and commonly present during active disease phases. The titers of these antibodies are closely associated with disease activity. Elevated anti-dsDNA titers in stable-phase patients may indicate a high risk of disease relapse, necessitating closer monitoring.

Anti-ENA Antibody Spectrum

This group includes antibodies with differing clinical significance:

- Anti-Sm Antibody: A diagnostic marker for SLE with 99% specificity but only 25% sensitivity; it aids in diagnosing atypical or early-stage cases.

- Anti-RNP Antibody: With a 40% positivity rate, it is not highly specific for SLE but is often associated with Raynaud's phenomenon and pulmonary hypertension in SLE.

- Anti-SSA (Ro) Antibody: Associated with photosensitivity, vasculitis, skin lesions, leukopenia, smooth muscle involvement, and neonatal lupus in SLE.

- Anti-SSB (La) Antibody: Often accompanies anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and is associated with secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, although its positivity rate is lower than that of anti-SSA.

- Anti-rRNP Antibody: Often indicates neuropsychiatric lupus (NPSLE) or other significant organ damage.

Antiphospholipid Antibodies

Includes anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulants, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies, which target different components of phospholipids. These antibodies, combined with specific clinical manifestations, help diagnose coexisting antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

Anti-Organ-Specific Antibodies

Includes anti-erythrocyte antibodies detected through Coombs tests, anti-platelet antibodies leading to thrombocytopenia, and anti-neuronal antibodies often seen in NPSLE.

Other Antibodies

Rheumatoid factor (RF) may be found in some patients’ serum, and a small number may have anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

Complement Levels

Common complement tests include total complement (CH50), C3, and C4. Low complement levels, particularly reduced C3, frequently suggest active SLE. Low C4 levels may indicate disease activity or represent SLE susceptibility due to C4 deficiency.

Indicators of Disease Activity

In addition to anti-dsDNA antibodies and complement levels, many other indicators signal disease activity, including changes in CSF, increased proteinuria, and elevated inflammatory markers such as accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and elevated serum C-reactive protein (CRP).

Renal Biopsy Pathology

Renal biopsy provides valuable information for diagnosing, treating, and prognosticating lupus nephritis, especially guiding treatment strategies.

X-ray and Imaging Studies

Imaging studies assist in identifying early organ damage. Brain MRI and CT can help identify and manage infarctions or hemorrhagic lesions in the central nervous system. High-resolution chest CT can detect early interstitial lung disease. Echocardiography has high sensitivity for identifying pericardial effusion, myocardial or valvular abnormalities, and pulmonary hypertension, aiding early diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

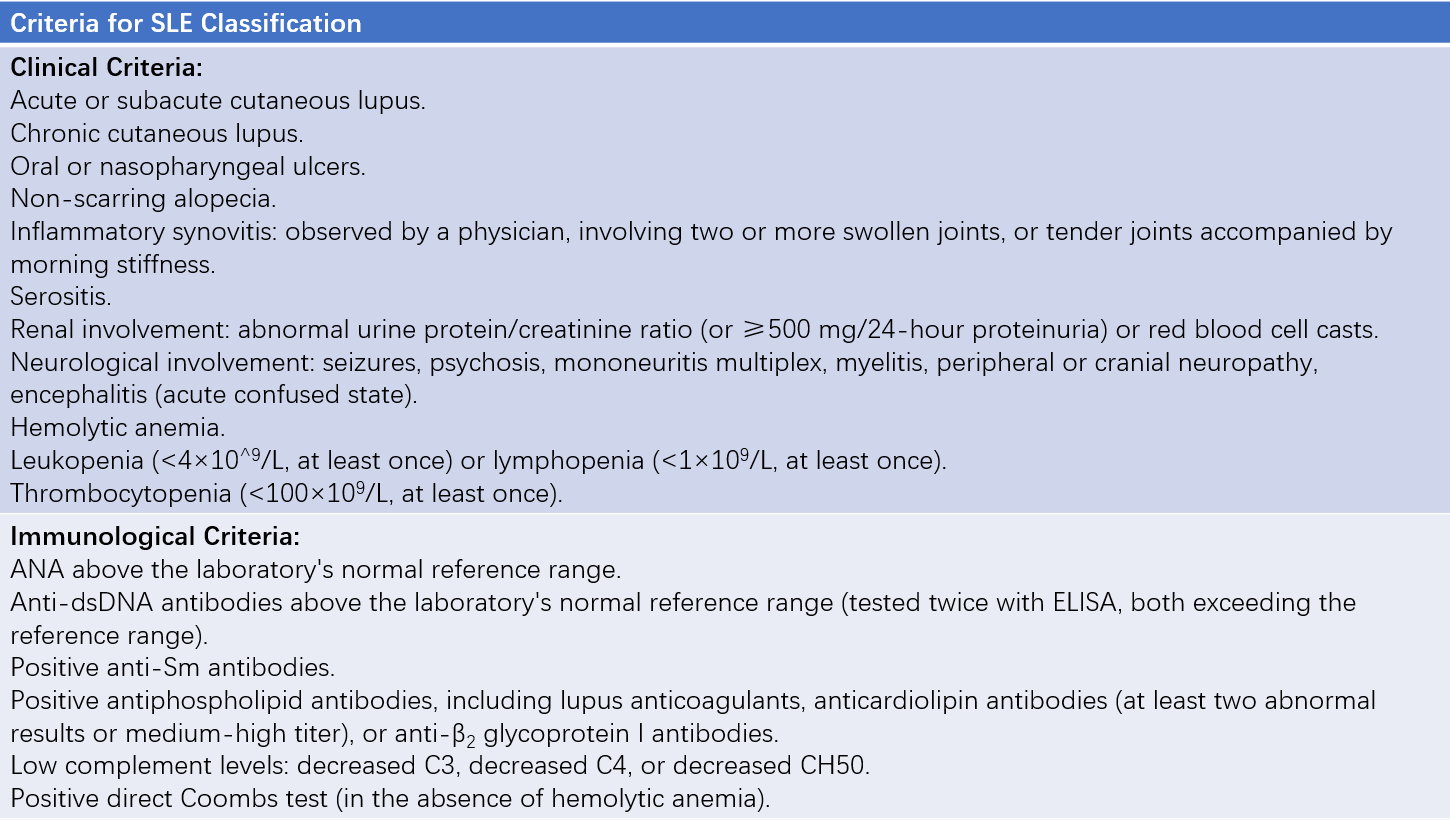

Diagnosis of suspected SLE is currently recommended based on the criteria established by the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) or the 2019 criteria proposed by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).

Under the 2012 criteria, a diagnosis of SLE can be made if a patient fulfills four criteria from the list of 11 clinical and six immunological items, including at least one clinical and one immunological criterion, or if biopsy-proven lupus nephritis is present alongside a positive ANA or anti-dsDNA test. The sensitivity and specificity for these criteria are 97% and 84%, respectively. However, it should be noted that classification criteria are primarily designed for research purposes to ensure homogeneity among study subjects. While these criteria aid in diagnosing typical cases in clinical practice, some SLE patients may not meet these criteria.

Table 1 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria for SLE classification

Note:

SLE diagnosis is confirmed by (1) Biopsy-proven lupus nephritis with a positive ANA or anti-dsDNA antibody and (2) Meeting four criteria overall, including at least one clinical criterion and one immunological criterion.

Given SLE’s multi-system involvement, each clinical manifestation must be distinguished from diseases affecting the corresponding system. The multiple autoantibodies and atypical presentations of SLE require differentiation from other connective tissue diseases and systemic vasculitides. Certain drugs, such as hydralazine, may induce lupus-like symptoms (drug-induced lupus), though nervous system involvement and nephritis are rare features. Drug-induced lupus is typically negative for anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies with normal complement levels, aiding differentiation.

Assessment of Disease Status

After confirming the diagnosis, the evaluation of disease status is necessary to determine appropriate therapeutic measures. The evaluation is generally based on the following three aspects:

Disease Activity or Acute Flare

Disease activity is assessed by the location and severity of organ involvement. Central nervous system involvement indicates severe disease, while renal involvement is considered more serious than fever or skin rashes. Among renal cases, lupus nephritis with renal insufficiency is more severe than cases presenting only with proteinuria. Lupus crises refer to acute, life-threatening severe forms of SLE, including rapidly progressive lupus nephritis, severe central nervous system damage, severe hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenic purpura, agranulocytosis, severe cardiac damage, severe lupus pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, severe lupus hepatitis, and severe vasculitis.

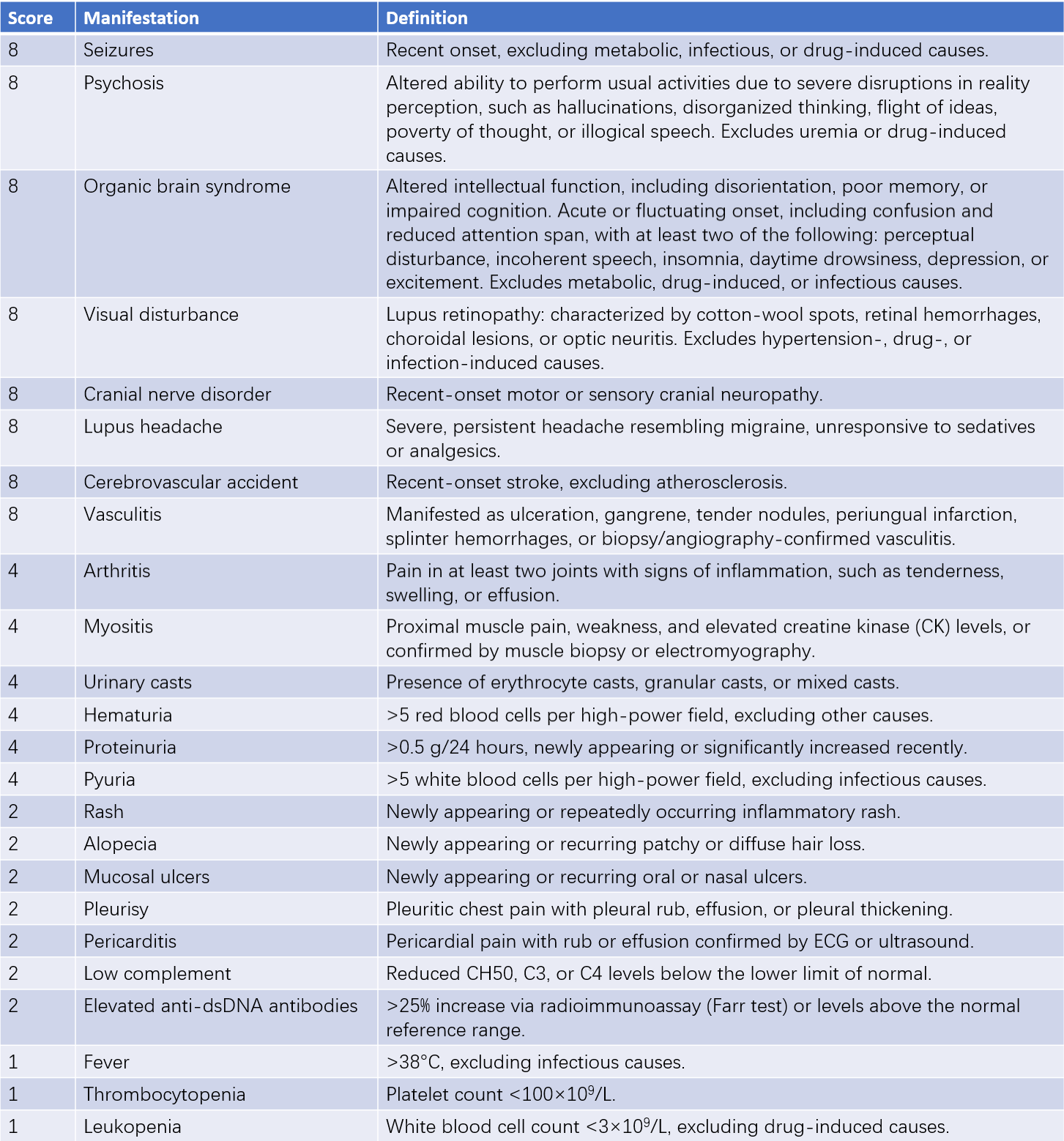

Several criteria are available to assess disease activity, including SLEDAI, SLAM, SIS, and BILAG. The SLEDAI is practical and relatively simple. It grades disease activity based on symptoms observed over the past 10 days, with a maximum score of 105. Scores ≤4 indicate stable disease, 5–9 indicate mild activity, 10–14 indicate moderate activity, and ≥15 indicate severe activity.

Table 2 Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI)

Organ Function and Irreversible Damage

As SLE progresses with repeated relapses, cumulative tissue damage occurs, compounded by adverse drug reactions from long-term glucocorticoid and immunosuppressant use. The extent of irreversible changes and organ dysfunction determines the long-term prognosis of lupus patients.

Complications

Complications such as atherosclerosis, infections, hypertension, and diabetes often exacerbate SLE and lead to a worse prognosis.

Treatment

SLE remains incurable, but individualized treatment can achieve long-term remission with proper management. Glucocorticoids combined with immunosuppressants remain the cornerstone of treatment. The treatment principle is to actively induce remission during acute phases by controlling disease activity as quickly as possible, adjust medications during remission, and maintain the remission state to preserve organ function and reduce medication side effects. Management also includes addressing comorbid conditions, such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and osteoporosis. Patient and family education is critical for improving treatment adherence, ensuring regular follow-ups, and seeking medical care promptly.

General Management

Non-pharmacological therapy plays an important role:

- Psychological counseling helps patients maintain optimism about their condition.

- Bed rest is recommended during acute flares, while stable chronic cases may engage in work with caution to avoid overexertion.

- Early detection and treatment of infections are necessary.

- Lupus-triggering drugs, such as oral contraceptives, should be avoided.

- Avoidance of strong sunlight and ultraviolet exposure is important.

- Immunizations may be administered during remission phases but should ideally avoid live vaccines.

Symptomatic Management

For fever and joint pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used. Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and osteoporosis are managed with appropriate treatments. Neurological or psychiatric symptoms in SLE may require interventions such as intracranial pressure reduction, anti-epileptic medications, or antidepressants.

Drug Therapy

Glucocorticoids

During the induction phase of remission, prednisone is used at doses of 0.5–1 mg/kg per day based on disease severity. For stable cases, the dose is gradually tapered after 2–6 weeks. Long-term maintenance with low-dose prednisone (<10 mg/day) is preferred if the condition allows. In lupus crises, pulse therapy with high-dose methylprednisolone (500–1,000 mg intravenously once daily for 3–5 days per treatment cycle) may be necessary. Repeat cycles may be administered after 1–2 weeks if required to rapidly control disease activity and induce remission.

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is recommended as a baseline therapy for all SLE patients without contraindications. It reduces disease activity, lowers the risk of organ damage and thrombosis, improves lipid profiles, and enhances survival rates. Eye examinations are advised for hydroxychloroquine users to monitor ocular risks. Patients at high risk may require annual ophthalmologic evaluations, while low-risk patients begin annual screening after 5 years of use.

Immunosuppressants

Most SLE patients, particularly those with active disease, require immunosuppressants as part of combination therapy. Adding immunosuppressants helps achieve better disease control, protect key organ function, reduce relapse rates, and minimize glucocorticoid dependency and associated side effects. For patients with major organ involvement, cyclophosphamide (CTX) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is recommended during induction therapy for at least 6 months in the absence of significant side effects. Maintenance therapy may involve one or two immunosuppressants based on the disease.

Biologic Agents

For patients with poor response, intolerance, or relapse despite glucocorticoid and/or immunosuppressant therapy, biologic agents may be considered. Biologics can significantly improve complete and partial remission rates, lower disease activity and relapse rates, and reduce glucocorticoid doses. Approved treatments include belimumab and telitacicept. Rituximab, though not officially approved for SLE treatment, is mentioned in guidelines as effective for refractory lupus nephritis and hematologic involvement in specific cases.

Other Therapies

Critical or treatment-resistant cases may benefit from intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasmapheresis based on clinical circumstances.

Prognosis

With advancements in early diagnostic techniques and improved SLE treatments, patient outcomes have significantly improved. Survival rates for SLE patients have increased from a 50% 4-year survival rate in the 1950s to an 80% 15-year survival rate, with 10-year survival rates now exceeding 90%. Acute-phase deaths are often caused by severe multi-organ damage or infections, particularly in cases with major neuropsychiatric lupus, pulmonary hypertension, or rapidly progressive lupus nephritis. Long-term mortality is primarily associated with chronic renal insufficiency, adverse effects of drugs (especially prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids), and complications such as coronary atherosclerotic heart disease.

As immunological research advances, long-term follow-up data from large SLE cohorts improve, new therapeutic agents emerge, and patient education and management strategies are strengthened, further improvements in SLE prognosis are anticipated.