Takayasu arteritis (TA) refers to a chronic granulomatous panarteritis involving the aorta and its primary branches, leading to stenosis or occlusion of the affected arteries. In some cases, arterial dilation or aneurysms may also occur, resulting in ischemia of the organs supplied by the affected vessels. It has previously been referred to as "pulseless disease" or "Takayasu’s disease." The incidence of TA is estimated to be 0.4 to 2.6 per 100,000 individuals, with a higher prevalence in Asia and the Middle East. For example, the incidence in Japan is estimated to be 40 per 100,000, compared to 4.7 to 8 per 100,000 in Europe and North America. The male-to-female ratio of incidence is 1:8–9. The onset generally occurs between the ages of 5 and 45, with approximately 90% of patients experiencing onset before the age of 30.

Etiology

The cause of TA remains unclear. It has been associated with genetic factors (e.g., HLA-DRB52*01 haplotype), infections (such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and herpes viruses), and sex hormones.

Pathology

Pathological changes are typically categorized into three stages:

Acute Phase

Inflammation originates around the vasa vasorum located at the junction of the middle and outer arterial walls and gradually involves the entire vessel wall. Inflammatory cell infiltration, segmental necrosis, and granuloma with multinucleated giant cells are observed in the affected arteries. There is disruption of elastic fibers and loss of smooth muscle in the media, alongside reactive fibrosis and increased extracellular matrix in the intima.

Chronic Phase

Fibrosis of the vessel wall occurs, with associated scar formation and vascular proliferation as well as sporadic inflammatory responses.

Scar Phase

Complete fibrosis of the arterial wall is evident, with thickening of the vessel walls leading to stenosis or occlusion. Thrombi may form. In cases of severe elastic fiber disruption and damage to smooth muscle, the vessel wall becomes thinner and dilated, potentially resulting in aneurysm formation.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical course of TA is divided into two phases:

Phase 1 (also referred to as the "pre-pulseless phase" or "systemic phase")

This phase is dominated by systemic inflammatory symptoms. Typical manifestations include fever, malaise, night sweats, arthralgia, anorexia, weight loss, and occasionally oral ulcers or erythema nodosum. Signs of vascular involvement may also be observed, such as neck vessel pain or tenderness, and back pain. Due to the nonspecific nature of the clinical features, delayed diagnosis is common. Careful physical examination may reveal vascular bruits in the neck, abdomen, or back.

Phase 2 ("pulseless phase")

Symptoms in this stage predominantly result from ischemia of tissues and organs. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the vascular involvement. The classification proposed by Numano divides TA into five types based on the affected blood vessels:

- Type I: Involves the branches of the aortic arch. Stenosis of the carotid and vertebral arteries causes varying degrees of ischemia to the head, presenting as headaches, dizziness, blurred vision, visual impairment, jaw claudication, and neck pain. Rarely, stroke may occur. Stenosis of the subclavian or axillary arteries results in symptoms such as upper limb weakness, coldness, pain, or numbness. Physical examination may reveal tenderness over affected vessels, weakened or absent carotid, radial, or brachial artery pulses, as well as vascular bruits in the neck or supraclavicular region.

- Type II: Involves the ascending aorta, descending aorta, and branches of the aortic arch. Clinical features are similar to those of Type I, with some patients experiencing back pain and vascular bruits detectable over the back.

- Type III: Involves the descending aorta and bilateral renal arteries. The predominant clinical feature is severe hypertension. Some patients may also exhibit involvement of abdominal aortic branches or the lower limb arteries, presenting with abdominal pain or intermittent claudication. Vascular bruits may be heard over the back or abdomen, and blood pressure in the lower limbs may be significantly lower than in the upper limbs.

- Type IV: Limited to the abdominal aorta and bilateral renal arteries. This type presents similarly to Type III but vascular bruits are not heard over the back.

- Type V: Involves the entire length of the aorta and its primary branches. Clinical manifestations include features of all the aforementioned types.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Non-specific changes such as elevated leukocyte count, thrombocytosis, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels may be observed during the acute phase or active disease stage. A small number of patients may test positive for anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECA) or anti-aorta antibodies.

Imaging Examinations

Color Doppler Ultrasound

Abnormalities in the carotid arteries, subclavian arteries, brachiocephalic trunk, and upper and lower limb arteries can be detected. Features include unclear boundary definitions of the vascular wall's three-layer structure, thickening of the wall, and luminal narrowing, which may present as the "macaroni sign." Severe disease or long disease duration may result in lumen occlusion and subsequent thrombus formation. Some patients may also exhibit aneurysmal dilatation of the arteries.

Angiography or Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA)

These modalities serve as diagnostic tools for confirming Takayasu arteritis. Findings include arterial wall thickening, luminal narrowing, and occlusion in the aorta and its primary branches. In some patients, vascular dilation and aneurysm formation may also be observed.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)

In addition to detecting the arterial abnormalities observed on angiography or CTA, MRA has the ability to reveal inflammatory edema signals in the vessel wall. This method is useful both for diagnosis and for assessing disease activity.

PET and PET-MRA

Positron emission tomography (PET) reveals increased uptake of isotopes in arterial walls where active inflammation is present. When combined with MRA, it can be used to evaluate disease activity and the extent of inflammation.

Diagnosis

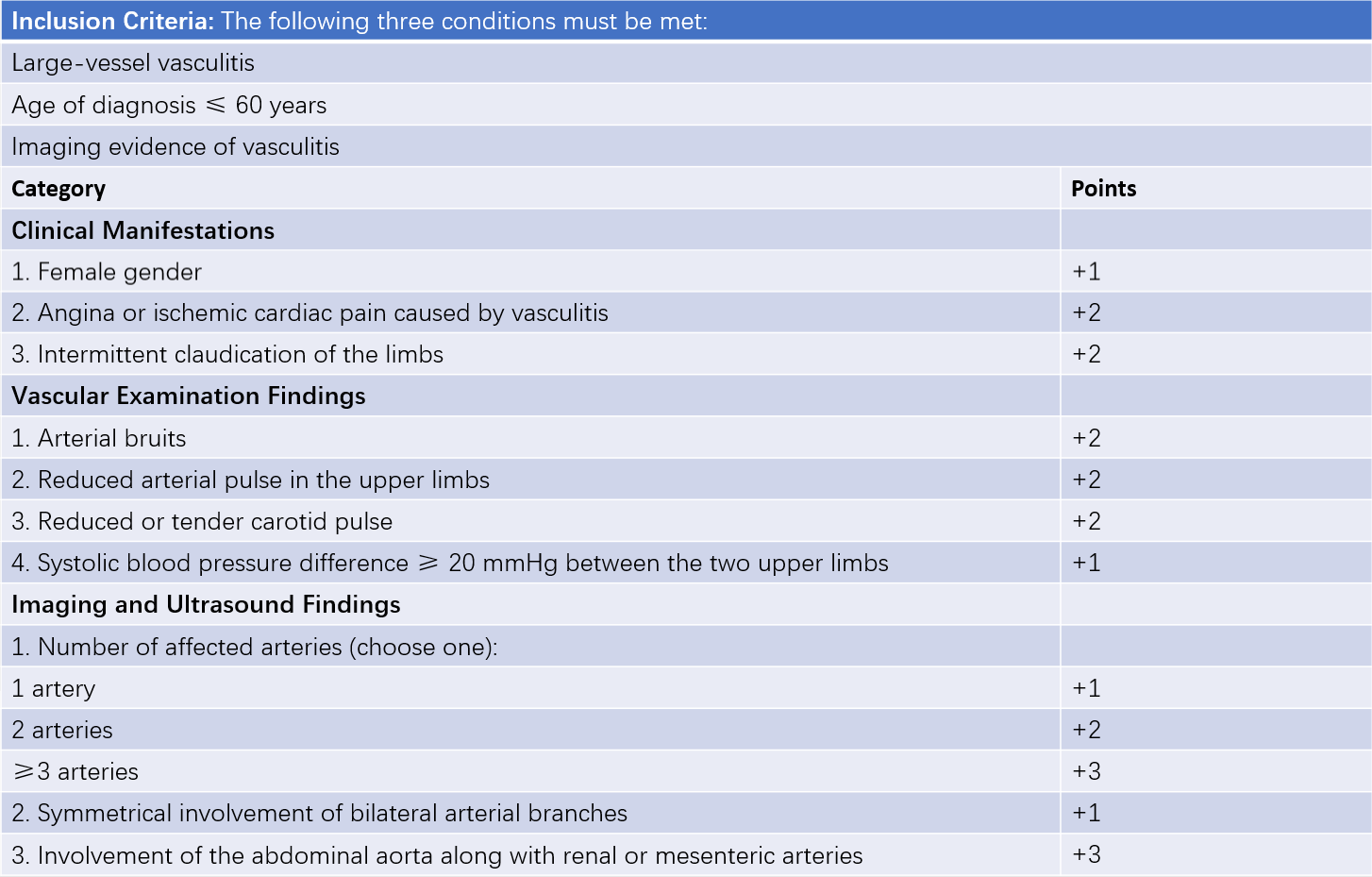

In 2022, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) jointly developed a new classification system for Takayasu arteritis. This system applies a weighted scoring method for classification, requiring evidence of clinical and imaging-based large-vessel inflammation and an onset age of ≤60 years. A total score of ≥5 points allows classification as Takayasu arteritis. However, other conditions such as congenital aortic coarctation, fibromuscular dysplasia, atherosclerosis, thromboangiitis obliterans, Behçet's disease, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), and thoracic outlet syndrome must be ruled out.

Table 1 2022 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for Takayasu arteritis (TA)

Treatment

The treatment approach focuses on controlling active disease and alleviating organ ischemia. For active phase patients, prednisone is administered at a dose of 1 mg/(kg·d), with a gradual reduction over 4–6 weeks until discontinuation. For rapidly progressive disease, high-dose glucocorticoid pulse therapy using methylprednisolone (500–1,000 mg) may be employed. Patients not responding adequately to glucocorticoids alone may be treated with immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide (CTX), azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil. Recent studies have shown that TNF-α antagonists and IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibodies are effective, particularly in refractory cases where glucocorticoids combined with conventional immunosuppressants fail or when tapering of steroids proves difficult.

For patients with significant organ ischemia due to vascular stenosis, life-threatening conditions, or severe impairment of quality of life, surgical interventions such as vascular reconstruction or stent placement may be considered. In cases of extensive vascular lesions, open vascular bypass surgery may be performed. For refractory hypertension caused by severe renal artery stenosis, nephrectomy can be considered.

Prognosis

Takayasu arteritis is a progressive disease that is rarely self-limiting. However, the majority of patients have a favorable prognosis. The 5-year survival rate is 93.8%, and the 10-year survival rate is 90.9%. The main causes of mortality include heart failure, cerebrovascular or cardiovascular events, renal failure, and surgical complications.