Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) refer to a heterogeneous group of diseases primarily affecting striated muscles, with or without skin involvement. These include dermatomyositis (DM), juvenile DM, antisynthetase syndrome, inclusion body myositis (IBM), amyopathic dermatomyositis (ADM), immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), polymyositis (PM), among others. Key clinical features involve symmetric proximal muscle weakness and elevated muscle enzyme levels, often accompanied by extramuscular manifestations such as rash, arthritis, interstitial lung disease (ILD), and cardiac involvement. The incidence rate is approximately 2.9 to 33 cases per 100,000 individuals, with two age-related peaks: 10–15 years and 45–65 years.

Etiology

The exact cause remains unclear. It is widely believed that the disease is immune-mediated, triggered by infectious or non-infectious factors in genetically predisposed individuals.

Pathology

The pathological features of IIM include muscle fiber swelling, disappearance of striations, transparent changes in the sarcoplasm, increased nuclei in muscle fibers, and inflammatory infiltration within the muscle tissue.

In PM, the infiltrating cells predominantly consist of CD8+ T lymphocytes, which are often concentrated around muscle fibers within the endomysium, forming CD8+/MHC Class I molecule complexes.

In DM, inflammatory infiltration is primarily observed with B cells and CD4+ T cells in the perimysium, epimysium, and around blood vessels, with perifascicular muscle atrophy and upregulation of MHC Class I expression on muscle fibers.

IMNM is characterized by extensive necrosis and/or regeneration of muscle cells, often accompanied by membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition.

IBM exhibits changes similar to PM, but with additional features such as rimmed vacuoles, inclusions, and amyloid deposition.

Skin pathology lacks significant specificity.

Clinical Manifestations

The disease is marked by symmetric proximal muscle weakness and can involve the skin, heart, lungs, and other organs.

Skeletal Muscles

Symmetric proximal muscle weakness and reduced muscular endurance represent the most prominent clinical presentations, typically with a subacute or insidious onset, reaching a peak over weeks to months. Some patients may experience spontaneous muscle pain and tenderness.

Pelvic girdle muscle involvement may result in weakness around the hips and thighs, causing difficulty in squatting or rising from a seated position.

Shoulder girdle muscle weakness can make arm elevation challenging, and neck flexor weakness occurs in roughly half the patients.

Involvement of the striated muscles of the pharynx and upper esophagus can lead to hoarseness, speech difficulties, choking on liquids, and dysphagia.

Skin

Cutaneous manifestations can appear before, concurrently with, or after the onset of myositis, and their severity often does not correlate with the degree of muscle involvement. Typical skin manifestations include:

- Heliotrope Rash: Red or purplish discoloration around the eyes, often accompanied by edema. Photosensitive rashes may occur on the face, V-area of the chest (V-sign), and shoulders or upper back (shawl sign).

- Gottron's Papules: Purplish-red papules on the extensor surfaces of the elbows, knees, metacarpophalangeal joints, or interphalangeal joints, often with fine scaling. Flat patches in similar distributions are referred to as "Gottron's sign."

- Mechanic's Hands: Thickened, cracked, rough, and peeling skin on the radial side of the palms.

- Periungual Changes: Erythema or petechiae with capillary dilation in the nailfolds.

- Holster Sign: Rashes over the lateral thighs resembling saddlebags.

Other manifestations may include skin atrophy, hyperpigmentation or depigmentation, telangiectasias, or subcutaneous calcifications.

Other Systems

Pulmonary Involvement

The lungs are the most commonly affected extramuscular organ. ILD, weakness in the thoracic and diaphragmatic muscles, and other pulmonary complications can cause respiratory difficulty. ILD is the most frequent pulmonary manifestation, with pathological types including non-specific interstitial pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, usual interstitial pneumonia, and diffuse alveolar damage. Some patients may experience rapidly progressive ILD (RP-ILD), which carries a poor prognosis and high mortality rate.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Distal esophageal dilation and reduced small intestine motility may result in symptoms such as acid reflux, esophagitis, dysphagia, upper abdominal discomfort, or malabsorption.

Joint Involvement

Patients often develop non-erosive, symmetric arthritis of the small joints in the hands and feet.

Malignancy-Associated Myositis

Some cases are associated with malignancy, termed paraneoplastic dermatomyositis.

Cardiac Involvement

Manifestations may include arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure.

Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM)

IBM commonly occurs in middle-aged and elderly individuals, characterized by slowly progressive muscle weakness and atrophy, often misdiagnosed as corticosteroid-resistant polymyositis (PM). It frequently presents with weakness in finger flexion, greater wrist flexor weakness compared to wrist extensor weakness, and quadriceps muscle weakness (≤ grade IV). Key pathological features include:

- Inflammatory cell infiltration localized to parts of individual muscle fibers, with other regions of the same fiber remaining intact.

- Rimmed vacuoles.

- Intracellular deposits of amyloid-like material.

- Tubulofilamentous inclusions observed in electron microscopy.

Amyopathic Dermatomyositis (ADM)

ADM is characterized by classic skin manifestations of dermatomyositis without objective evidence of muscle involvement. It accounts for 2%–21% of dermatomyositis cases. While it primarily affects the skin, systemic organ involvement can also occur. In some cases, ADM may progress to interstitial lung disease (ILD), which can be severe and rapidly progressive.

Anti-MDA5 Antibody-Positive Dermatomyositis

This form of dermatomyositis is marked by the presence of anti-melanoma differentiation antigen 5 (anti-MDA5) antibodies. Clinical features include prominent skin lesions and rapidly progressive ILD (RP-ILD). It predominantly affects women in Asian populations and is associated with rapid deterioration and poor prognosis.

Immune-Mediated Necrotizing Myopathy (IMNM)

IMNM is characterized by acute or subacute onset, with severe proximal muscle weakness (predominantly in the lower limbs) and potential involvement of neck flexors, respiratory muscles, and others. It is often associated with the presence of anti-signal recognition particle (SRP) antibodies or anti-HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) antibodies and presents with significantly elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels. IMNM generally shows poor response to corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, and irreversible muscle damage may persist even after disease activity subsides, preventing full recovery of muscle strength in some patients.

Supplementary Examinations

General Laboratory Tests

Mild anemia may be detected on routine blood tests, with normal or reduced leukocyte counts. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels may be observed or remain normal. Serum myoglobin levels are elevated, and myoglobinuria may occur with extensive muscle damage.

Serum Muscle Enzymes

Levels of creatine kinase (CK), aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are typically elevated, with CK being the most sensitive indicator. CK levels vary among different subtypes of IIM. Elevated CK often precedes clinical relapse and can be used to monitor disease progression and treatment efficacy, although it does not fully correlate with the degree of muscle weakness.

Autoantibodies

Autoantibodies found in patients with myositis include myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSA) and myositis-associated autoantibodies (MAA). Some MSAs are more strongly associated with extramuscular manifestations, such as skin and lung involvement, rather than myositis itself. The coexistence of more than one MSA in a single individual is rare. Each MSA correlates with a unique disease pattern or phenotype, aiding in understanding the immune mechanisms underlying myositis, improving diagnosis, and developing individualized treatments.

Myositis-Specific Autoantibodies (MSA)

Anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase antibodies: These include anti-Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12, EJ, OJ, KS, Zo, and YRS antibodies. Anti-Jo-1 antibodies are the most frequently detected and are associated with interstitial lung disease, fever, arthritis, "mechanic's hands," and Raynaud's phenomenon, collectively termed "antisynthetase syndrome."

Anti-Mi-2 antibodies: A classic marker of dermatomyositis, identified in approximately 30% of adult and 10% of juvenile dermatomyositis cases. Patients with these antibodies often exhibit rash in 95% of cases, mild myopathy, and reduced risk of ILD or malignancy. The presence of these antibodies is associated with good responsiveness to corticosteroid therapy and favorable prognosis.

- Anti-MDA5 antibodies: Frequently observed in ADM patients, often associated with RP-ILD and poor prognosis.

- Anti-TIF-1γ antibodies: Commonly linked to malignancy in adults and occasionally associated with dark red rashes, photosensitive erythema, a "drunken appearance," and frontal hairline rashes. ILD is rare in these patients.

- Anti-NXP2 antibodies: More commonly seen in younger patients, associated with severe skin and muscle involvement, calcinosis, ischemic muscle damage, and malignancy.

- Anti-SAE antibodies: Often accompanied by dysphagia and hyperpigmented rashes, with skin lesions typically preceding muscle symptoms. Muscle weakness and ILD are rare, and the prognosis is generally favorable.

- Anti-SRP and anti-HMGCR antibodies: Specific biomarkers for IMNM, commonly associated with acute necrotizing myopathy, severe muscle damage, markedly elevated muscle enzymes, poor muscle strength, and rare skin or ILD manifestations. Poor response to corticosteroids is typical. Some patients with anti-HMGCR antibodies have a history of statin use and exhibit significant muscle weakness.

- Anti-cN1A antibodies: The only known antibody specifically associated with IBM.

Myositis-Associated Antibodies (MAA)

MAAs are autoantibodies detected in conditions that may involve myositis, such as systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Examples include anti-SSA (Ro52, Ro60), anti-SSB (La), anti-PM-Scl, anti-Ku, and anti-U1RNP antibodies.

Electromyography (EMG)

Typical findings on EMG suggest myogenic damage, characterized by low-amplitude, short-duration, polyphasic waves; increased insertional irritation (e.g., positive sharp waves or spontaneous fibrillations); and spontaneous, irregular, high-frequency discharges.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is useful in detecting active muscle inflammation (edema), guiding biopsy site selection, and identifying active lesions in patients with normal muscle enzyme profiles.

Muscle Biopsy

Approximately two-thirds of cases show typical inflammatory myopathy pathological features, while one-third may present with atypical or even normal findings. Immunopathological analysis can aid in further diagnostic clarification.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

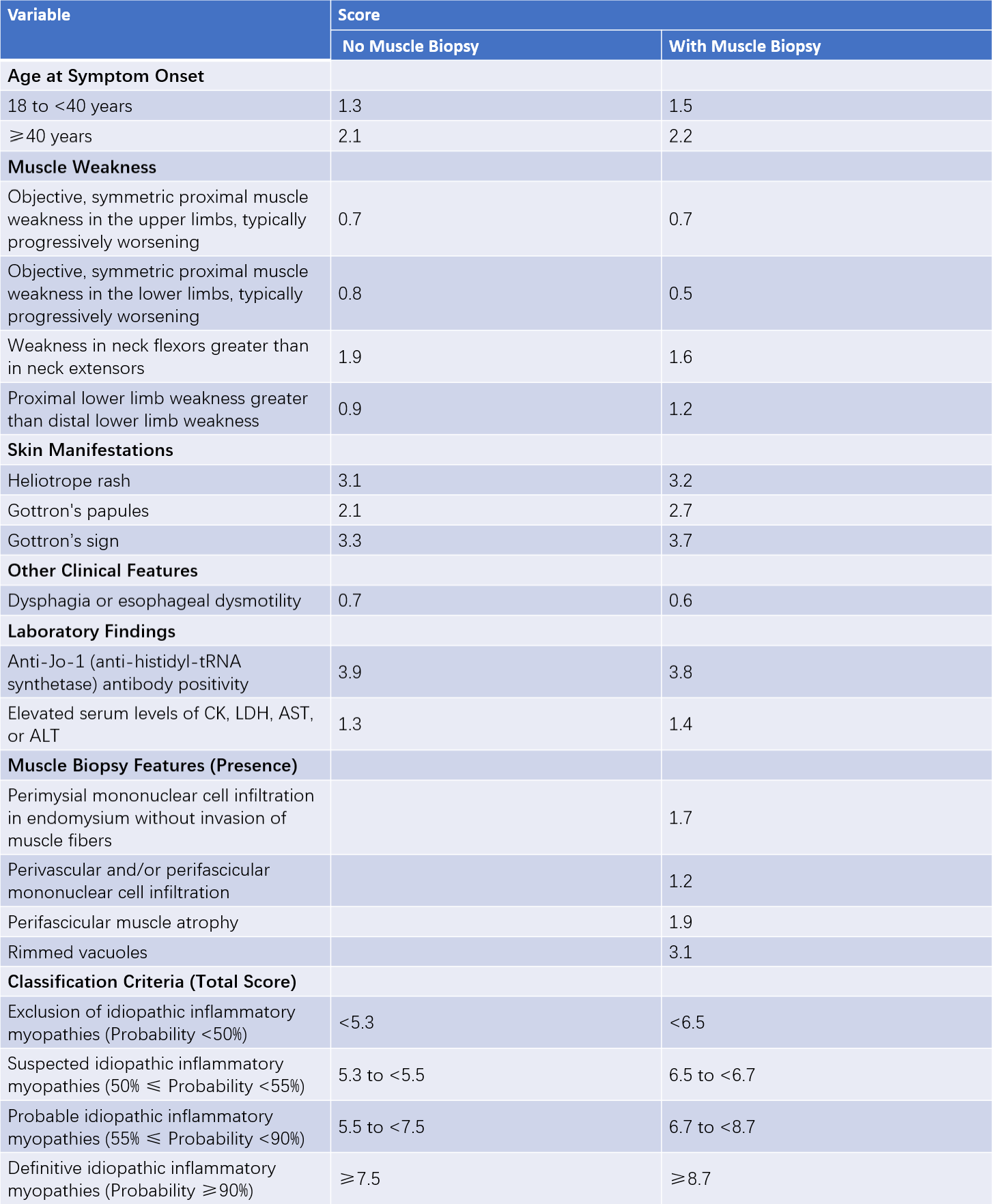

Currently, there are no definitive diagnostic criteria for IIM (idiopathic inflammatory myopathies). The most recent classification criteria for adult and juvenile IIM were proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2017.

Table 1 2017 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies

Once IIM is identified, classification is based on the age at onset, clinical manifestations, and muscle biopsy features. For patients with an age of onset younger than 18 years: a diagnosis of juvenile dermatomyositis (juvenile DM) is made if typical skin rashes are present, and juvenile myositis if typical rashes are absent. For patients aged 18 years or older: a diagnosis of DM is made if typical skin rashes and muscle weakness are present, and amyopathic dermatomyositis (ADM) if typical rashes are present without muscle weakness. For patients 18 years or older without typical skin rashes, the condition is usually diagnosed as polymyositis (PM) or immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM). If finger flexor weakness is observed, with poor treatment response or rimmed vacuoles on muscle biopsy, a diagnosis of inclusion body myositis (IBM) is made.

Treatment

Treatment principles emphasize individualization, with comprehensive patient evaluation being critical. Glucocorticoids are the first-line therapy. Prednisone is commonly initiated at a dose of 0.75–1 mg/(kg·day) for a duration of 4–6 weeks, with serum CK levels monitored and muscle strength assessed throughout. Gradual tapering of glucocorticoids is typically performed, or an additional immunosuppressive agent is introduced. Options include methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or mycophenolate mofetil. Severe cases may require pulse therapy with methylprednisolone, immunosuppressive agents, or high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. For skin involvement, hydroxychloroquine may be added.

Other therapies, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, CD20 monoclonal antibodies, JAK inhibitors, IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibodies, and plasma exchange, have shown favorable outcomes in a small number of cases, although large-scale studies are lacking. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) represents a key therapeutic focus and is a critical determinant of prognosis.

For severely affected patients, bed rest is advisable during the acute stage, but progressive physical activity should be incorporated to aid muscle strength recovery.