Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common heterogeneous joint disease, primarily characterized by cartilage damage but also involving the entire joint structure. Eventually, OA results in cartilage degeneration, fibrosis, fractures, ulcers, and damage to the entire joint surface. Its clinical manifestations include joint pain, stiffness, and restricted mobility. Historically, OA was considered a purely degenerative cartilage disease, while modern medicine recognizes OA as a whole-joint disease closely associated with metabolism and inflammation. With the accelerating aging process of the population and rising obesity prevalence, the incidence of OA is increasing. Moreover, OA is often accompanied by comorbid conditions, the most common of which include inflammatory joint diseases, hypertension, and metabolic disorders.

Epidemiology

OA is most prevalent among middle-aged and elderly individuals and is a leading cause of disability in older populations. Its prevalence is related to factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, and geographical distribution, and varies based on the definition and affected joint. Symptomatic knee OA occurs in 7%–17% of individuals over the age of 44. Hand OA is more common in women, while hip involvement is more frequent in older men compared to women.

Etiology

Major risk factors for OA include age, sex, obesity, genetic predisposition, joint structure and alignment abnormalities, trauma, occupations or sports activities that require repetitive use of specific joints, and smoking, among others.

Pathogenesis

The development of OA results from the interaction between multiple external factors and susceptible individuals. Biomechanical, biochemical, inflammatory, genetic, and innate immunological factors all contribute to its pathogenesis. These factors trigger low-grade inflammation, ultimately leading to characteristic changes in articular cartilage and affecting all joint structures. OA can be considered a group of diseases with different causes and overlapping factors, making it a heterogeneous condition with various subtypes.

Pathology

The disease primarily targets articular cartilage but can also affect the entire joint, including subchondral bone, synovium, ligaments, joint capsules, and periarticular muscles. It progresses to cartilage degeneration, fibrosis, fractures, ulcers, and joint surface destruction.

Cartilage

Cartilage degeneration is the fundamental pathological change in OA. Initially, it presents as focal softening and loss of normal elasticity, followed by the development of small cracks, rough textures, erosion, and ulcers. Large sections of cartilage may detach, exposing the subchondral bone plate. Microscopic examination reveals progressive structural disorganization and degeneration of the cartilage, reduced chondrocyte numbers, matrix mucoid degeneration, cartilage fibrillation or tearing, and connective tissue or fibrocartilage covering ulcerated areas, often accompanied by neovascularization. Ultimately, the entire cartilage layer disappears.

Subchondral Bone

Subchondral bone can show signs of bone marrow edema, osteoporosis, followed by thickening and sclerosis. Osteophyte formation occurs along the joint margins, and bone cysts may develop near the joint.

Synovium

Synovial inflammation is typically a secondary event, arising later in the disease process and being less severe than the inflammation observed in rheumatoid arthritis.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of osteoarthritis (OA) is generally insidious, with slow progression. The primary manifestations include pain, tenderness, stiffness, swelling, bony enlargement, and functional impairment in the affected joints and surrounding areas. Clinical symptoms vary depending on the joint involved. Pain typically occurs after activity and is alleviated by rest. As the disease progresses, pain intensifies during weight-bearing activities and may eventually present as resting pain or night pain. Since normal cartilage lacks nerve supply, pain arises primarily from involvement of other joint structures, such as the synovium, periosteum, subchondral bone, surrounding muscles, and ligaments. Morning stiffness is usually short-lasting, generally no more than 30 minutes. Some patients may exhibit signs of peripheral or central sensitization to pain. Those experiencing severe, persistent pain are often accompanied by anxiety and depressive states.

Commonly Affected Joints

OA predominantly affects weight-bearing joints, such as the knees, hips, cervical spine, and lumbar spine, as well as distal and proximal interphalangeal joints, the thumb carpometacarpal joint, and the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Other involved joints may include the intertarsal joints, ankle joint, acromioclavicular joint, temporomandibular joint, and elbow joint.

Hand OA

This is more common among middle-aged and elderly women, most frequently involving the distal interphalangeal joints, though the proximal interphalangeal joints and thumb carpometacarpal joint can also be affected. Characteristic features include bony nodules on the lateral and medial aspects of the interphalangeal joints. Those at the distal interphalangeal joints are called Heberden's nodes, while those at the proximal interphalangeal joints are referred to as Bouchard's nodes, and both have a genetic predisposition. The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints may take on snake-like deformities due to horizontal bending, and some patients may develop flexion or lateral deviation deformities. Thumb carpometacarpal joint OA may result in a "square hand" appearance.

Knee OA

Early stages are characterized by pain and stiffness, often involving one or both knees alternately and exacerbated during activities such as climbing stairs. Physical examination may reveal joint swelling, tenderness, crepitus, and varus deformity. As the disease progresses, patients may experience imbalance during walking, difficulty squatting or descending stairs, limited mobility, and the inability to bear weight. Sudden episodes of joint "giving way" may occur during activity. Additionally, patients might experience "locking" of the joint, which can be caused by intra-articular loose bodies or floating cartilage fragments.

Hip OA

This is more common in older adults, with a higher prevalence among males. The primary symptom is gradually developing pain that may radiate to the lateral hip, groin, or inner thigh and, in some cases, may localize to the knee, causing the primary site of disease to be overlooked. Physical examination may reveal varying degrees of restricted motion and a limping gait.

Foot OA

The first metatarsophalangeal joint is the most commonly affected. Symptoms may be exacerbated by tight footwear. The intertarsal joints can also be involved. In some cases, patients may develop redness, swelling, warmth, and pain in the joints, resembling gout, but with less severe pain. Physical examination may reveal bony enlargement and hallux valgus.

Special Types of OA

Erosive OA

Primarily involves the interphalangeal joints with significant pain and tenderness and may include gelatinous cyst formation and prominent inflammatory features. Radiographic findings show evident bone erosion.

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH)

Characterized by bony bridging along the margins of the spine and osteophyte formation in peripheral joints. It is more common in older adults and is unrelated to HLA-B27.

Rapidly Progressive OA

Seen most frequently in the hip joint with intense pain. It is diagnosed when there is a reduction of 2 mm or more in joint space within six months.

Laboratory and Imaging Examinations

There are no specific laboratory markers for OA. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are typically normal or mildly elevated, and rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies, and other autoantibodies are negative. Radiographic imaging is crucial for diagnosis, with characteristic X-ray findings including subchondral bone sclerosis, bone cysts, osteophyte formation at joint margins, and asymmetric narrowing of the joint space in affected joints. The severity of radiographic changes may not correlate with pain levels, indicating that the pain mechanism is complex and influenced by multiple factors. Joint ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify abnormalities such as synovitis, early cartilage damage, and bone marrow edema, facilitating early diagnosis.

Diagnosis

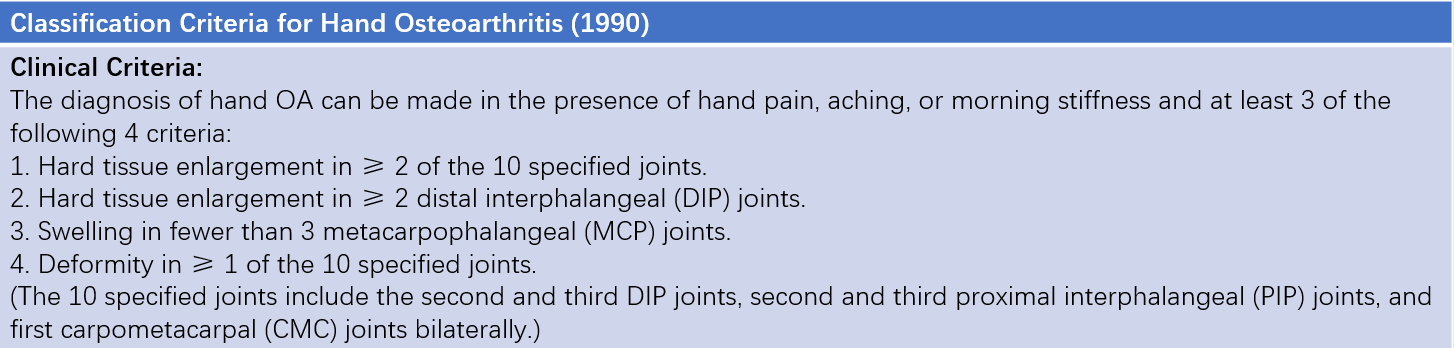

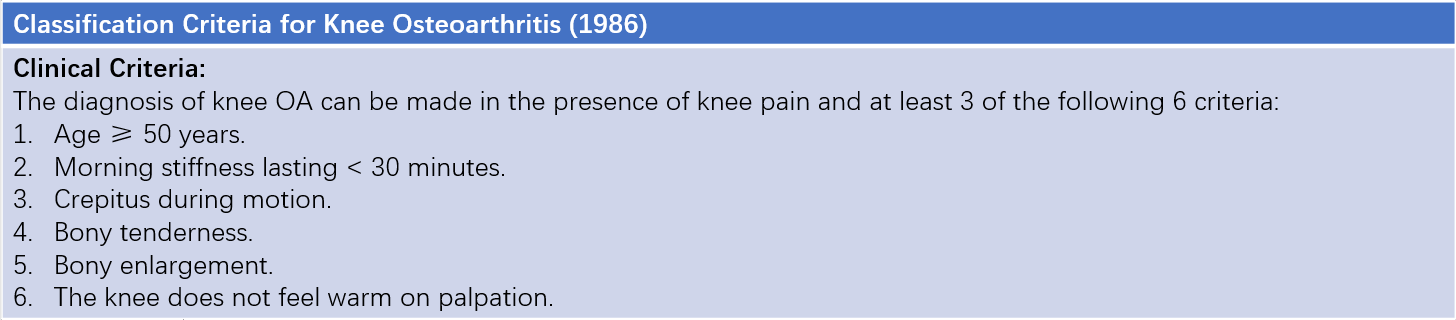

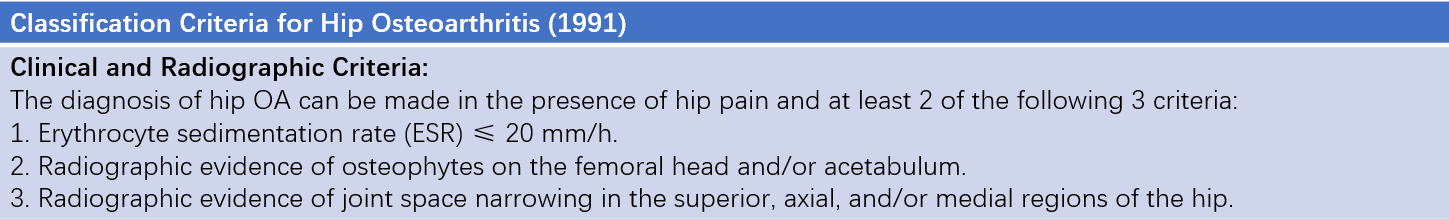

The diagnosis of OA is typically based on clinical manifestations and X-ray findings, excluding other inflammatory joint conditions. The American College of Rheumatology has established classification criteria for hand, knee, and hip OA.

Table 1 Classification criteria for hand osteoarthritis (1990)

Table 2 Classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis (1986)

Table 3 Classification criteria for hip osteoarthritis (1991)

Differential Diagnosis

Hand and knee OA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and pseudogout. Hip OA should be distinguished from hip tuberculosis and avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Spinal OA should be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis.

Treatment

The objectives of osteoarthritis (OA) treatment are to alleviate pain, preserve joint function, and improve quality of life. Treatment should be individualized, guiding patients toward non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies based on their specific conditions.

Non-Pharmacological Therapy

Non-pharmacological therapy is the cornerstone of OA management, encompassing patient education, exercise, and weight reduction when necessary. Exercise serves as the foundation of OA treatment. All OA patients, regardless of age, comorbidities, severity of pain, or level of functional impairment, should incorporate physical activity into their treatment regimen. However, the development of a personalized program is essential for optimal outcomes. In obese patients, weight reduction alone can significantly relieve symptoms of OA. Certain physical therapy modalities, such as acupuncture, hydrotherapy, and paraffin therapy, may also provide some therapeutic benefits.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological therapy includes symptomatic control medications, disease-modifying drugs, and chondroprotective agents.

Symptomatic Control Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which possess both analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, are the most commonly used medications for symptom control in OA. The lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest possible duration, and the type and dosage of medication should be individualized. In mild cases, topical NSAID preparations and/or capsaicin cream can relieve joint pain with minimal side effects. For patients where topical medications fail to provide relief, oral NSAIDs can be administered. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal issues, liver or kidney dysfunction, and an increased risk of cardiovascular events. For patients with pain sensitization, antidepressants such as duloxetine may be used. Systemic use of glucocorticoids should be avoided. However, for severe cases involving acute flare-ups, intense pain, nocturnal pain, or joint effusion, intra-articular injection of corticosteroids can quickly relieve symptoms, with effects lasting several weeks to months. Repeated injections in the same joint should be avoided, and the interval between injections should be no less than three months.

Disease-Modifying Drugs and Chondroprotective Agents

Currently, there is no universally recognized ideal drug to protect joint cartilage or slow the progression of OA. Commonly used agents include glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, diacerein, and intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid. Evidence from clinical studies on their efficacy is inconsistent, but they may offer some benefit.

Surgical Treatment

Joint replacement surgery may be considered for patients whose joint pain significantly impairs daily life and for whom non-surgical treatments have proven ineffective. This intervention can effectively alleviate pain and restore joint function. For patients with pronounced knee varus or valgus deformities, alignment correction surgery may be performed.

Prognosis

OA carries a certain risk of disability. In the United States, OA is the second leading cause of work disability among men over 50 years old. It is also a major reason for loss of work capacity and independence in middle-aged and older populations.