Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a rare systemic disease characterized by recurrent, immune-mediated inflammation primarily involving cartilage structures and proteoglycan-rich tissues. The annual incidence rate ranges from 0.35 to 9.0 per million, and the disease most commonly occurs between the ages of 40 and 60, with no significant sex differences. About 1/3 of patients may also develop systemic vasculitis and other rheumatic diseases, hematologic conditions such as myelodysplastic syndromes, or malignancies.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of RP is unclear. It is thought to involve an immune response, in genetically susceptible individuals, triggered by cartilage antigens exposed due to factors such as trauma, infection, or chemical insults that disrupt cartilage structures.

Clinical Manifestations

RP shows significant heterogeneity in clinical presentation, characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation and periods of remission. The primary symptoms involve inflammation of the ears, nose, throat, trachea, and bronchi, as well as potential involvement of the cardiovascular system, joints, eyes, skin, kidneys, nervous system, and hematopoietic system.

The most common and characteristic feature is auricular chondritis, which presents as sudden redness, swelling, and pain of the auricle sparing the earlobe. This inflammation may resolve spontaneously within days to weeks but often recurs, leading to flaccidity, collapse, deformities, and pigment deposition of the outer ear, described as "cauliflower ear" or "floppy ear." Narrowing of the external auditory canal, middle ear inflammation, and Eustachian tube obstruction may result in conductive hearing loss. Inner ear involvement can cause sensory hearing loss and/or vestibular dysfunction.

Nasal cartilage involvement may lead to nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, epistaxis, mucosal erosion, and nasal stiffness. Repeated inflammation can result in "saddle nose" deformity.

Approximately half of the patients exhibit involvement of the laryngeal, tracheal, and bronchial cartilage. This presents as throat pain and tenderness, hoarseness, irritative cough, dyspnea, and inspiratory stridor, often accompanied by respiratory infections. Inflammation of the laryngeal and epiglottic cartilage can lead to upper airway collapse, causing asphyxia, and, in severe cases, tracheostomy may be required.

About 30% of patients experience cardiovascular involvement, which may include myocarditis, endocarditis, cardiac conduction blocks, aortic regurgitation, and vasculitis affecting arteries of various sizes.

Approximately 70% of patients exhibit joint involvement, commonly presenting as asymmetric, episodic, and non-erosive arthritis. Ocular inflammation often manifests as scleritis, which may lead to thinning of the sclera and the appearance of a bluish hue. Other manifestations include conjunctivitis, uveitis, ulcerative or necrotizing keratitis, retinal vasculitis, or optic neuritis. Skin lesions include erythema nodosum, purpura, mucosal ulcers, livedo reticularis, and digital necrosis.

Auxiliary Examinations

There are no specific serological markers for RP. Antibodies such as anti-chondrocyte antibodies, anti-type II collagen antibodies, and anti-matrilin-1 antibodies may assist in diagnosis. Chest CT scans and fiberoptic bronchoscopy may reveal widespread narrowing of the trachea and bronchi. Pulmonary function tests may indicate obstructive ventilatory dysfunction. PET-CT can detect asymptomatic chondritis in its early stages.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

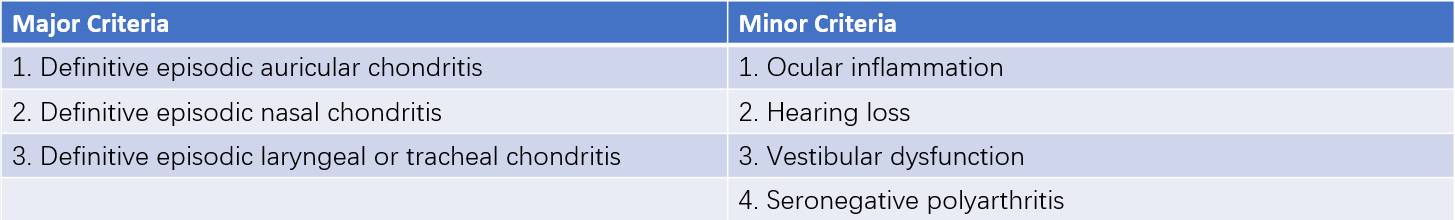

Clinicians still rely on the diagnostic criteria proposed by Michet in 1986.

Table 1 1986 Michet criteria for relapsing polychondritis

Note: A diagnosis is established with 2 major criteria or 1 major criterion plus 2 minor criteria.

Auricular involvement should be differentiated from conditions such as trauma, frostbite, erysipelas, chronic infections, gout, and syphilis. Nasal cartilage inflammation should be differentiated from granulomatous diseases such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, tuberculosis, and syphilis. A significant proportion of patients with vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked autoinflammatory, and somatic (VEXAS) syndrome are clinically diagnosed as RP.

Treatment

During the acute phase, patients are advised to rest in bed, maintain airway patency, and take measures to prevent asphyxia. For mild cases, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or colchicine may be administered. Severe cases are treated with corticosteroids, with an initial dose of 0.5–1 mg/(kg·d). For patients with acute severe involvement of the pharynx, trachea and bronchi, eyes, inner ear, or systemic vasculitis, the corticosteroid dosage may be appropriately increased or high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy may be employed. Once symptoms improve, the corticosteroid dosage may be gradually reduced and maintained at the minimum effective dose for 1–2 years or longer. Additional immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, leflunomide, azathioprine, or calcineurin inhibitors may be used as needed. Dapsone has shown potential efficacy in treating cartilage inflammation and arthritis in some patients. For refractory or relapsing cases, small-sample studies have reported the use of TNF-α inhibitors, IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibodies, IL-1 receptor monoclonal antibodies, selective T-cell costimulation modulators, or JAK inhibitors. Continuous positive airway pressure ventilation may prevent the collapse of softened airways and alleviate airway obstruction. For significant or extensive tracheal or bronchial stenosis, metal stents may be inserted under fiberoptic bronchoscopy or X-ray guidance.

Prognosis

Most patients exhibit a chronic disease course with a relatively favorable prognosis. Common causes of mortality include infections, airway involvement, and vasculitis. Other factors associated with poor prognosis include cardiac valvular disease, renal involvement, comorbid malignancies, and anemia.