Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic, non-articular rheumatic disorder characterized primarily by widespread diffuse pain and stiffness, often accompanied by fatigue, weakness, sleep disturbances, emotional abnormalities, and cognitive dysfunction. Tender points are present in specific areas. The prevalence is approximately 2%, with rates of 3%–4% in women and 0%–5% in men, increasing linearly with age. The average age of onset is 49 years, with 90% of cases occurring in women. The peak prevalence is observed in those aged 70–79 years.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The exact cause of FMS is unknown. Current understanding suggests associations with genetic predisposition, sleep disturbances, neuroendocrine dysregulation, immune abnormalities, alterations in the levels of certain naturally occurring amino acids, and psychological factors. Secondary FMS results from conditions such as trauma, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or malignancies. Cases without accompanying disorders are classified as primary FMS.

The underlying mechanism remains unclear. Studies have shown that muscle pain in FMS patients originates from nerve endings, specifically nociceptors. Mechanical traction, compression, chemical mediators such as substance P, bradykinin, potassium ions, and ischemic muscle contraction can stimulate nerve endings, leading to pain. Approximately 1/3 of patients have reduced serum levels of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and amino acids related to growth hormone, with changes in cerebrospinal fluid also correlating with the pain experienced in FMS. Furthermore, FMS may occur secondary to conditions like osteoarthritis or intervertebral disc herniation. Nociceptive pain caused by these diseases can repeatedly stimulate neurons in the second dorsal horn of the spinal cord, resulting in central sensitization, which eventually manifests as the chronic pain typical of FMS.

Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Symptoms

The core feature of FMS is chronic, widespread muscle pain, often accompanied by cutaneous tenderness, with varying intensity over time. Thirteen percent of patients experience diffuse muscle pain, while 43% have localized pain, primarily in axial skeletal regions (such as the neck, chest, and lower back), shoulder girdle, and pelvic girdle muscles. Other commonly affected areas include the knees, head, elbows, ankles, feet, upper back, mid-back, wrists, buttocks, thighs, and calves. FMS pain is diffuse, with patients perceiving it in muscles, joints, nerves, and bones, but unable to precisely localize it.

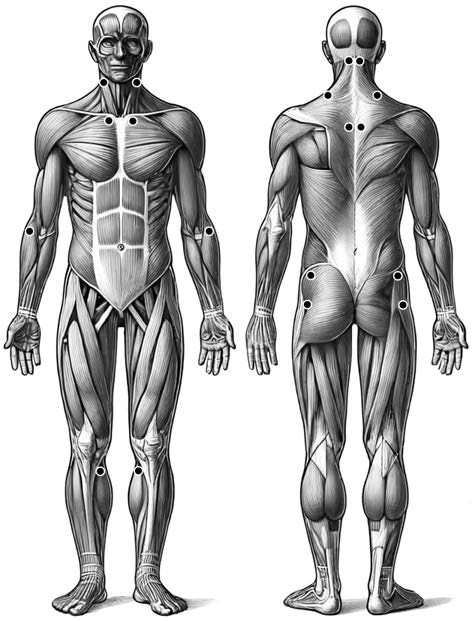

All patients exhibit tender points, distributed consistently and often symmetrically. Physical examination frequently reveals 9 paired (18 total) anatomical sites of tenderness:

- Bilateral muscle attachment points below the occipital bone

- Anterior interspaces between the transverse processes of the 5th and 7th cervical vertebrae

- Midpoints on the upper edges of bilateral trapezius muscles

- Origin points near the medial edges of the scapular spine bilaterally

- Superior lateral edges at the junction of the second rib and cartilage bilaterally

- 2 cm distal to the lateral epicondyles of the humerus bilaterally

- Anterior folds of the gluteal muscles in the upper outer quadrants bilaterally

- Posterior to the bilateral greater trochanters

- Inner folds of the fat pads along the knee joint lines bilaterally

Figure 1 Illustration of the 18 tender point locations in fibromyalgia syndrome

Women tend to have more tender points than men, with 90% of patients reporting 11 or more tender points being female. Triggers for pain include soft tissue injuries, sleep deprivation, cold weather, and emotional stress, with damp climates or low atmospheric pressure worsening symptoms. Morning stiffness is reported by 76%–91% of patients, and its severity correlates with sleep disturbances and disease activity. The morning stiffness experienced in FMS resembles that observed in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the "gel phenomenon" in polymyalgia rheumatica but lacks specificity and is not diagnostic.

Other Symptoms

Approximately 90% of patients report sleep disturbances, including insomnia, frequent awakenings, vivid dreams, and low energy levels. Over half experience severe fatigue, sometimes to the extent of feeling unable to work. Headaches are common, including migraines and dull, pressing pain in the occipital region or throughout the head. Other symptoms include dizziness, shortness of breath, limb numbness, abnormal sensations, depression, or anxiety, although neurological examinations are often unremarkable. Patients frequently report joint pain with accompanying morning stiffness but lack objective signs such as joint swelling.

More than 30% of patients develop irritable bowel syndrome, which manifests as bloating, abdominal pain, loose stools, and increased bowel movement frequency. Some experience general weakness, night sweats, dry mouth, and dry eyes. Additional features may include bladder irritability, pelvic pain, Raynaud's phenomenon, restless leg syndrome, and so on. Symptoms may exacerbate in cold, damp weather, during periods of mental stress, or after excessive physical activity. Conversely, symptoms may improve with localized warming, mental relaxation, good sleep, and moderate activity.

Laboratory Tests

Tests such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and autoantibodies often yield no abnormal findings. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain may reveal abnormal activation responses in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate gyrus, as well as disrupted fiber connectivity between these areas.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made based on the presence of chronic widespread muscle pain and stiffness that are often accompanied by sleep disturbances, including insomnia, frequent awakenings, vivid dreams, and low energy levels. Commonly affected areas include the neck, chest, lower back, shoulder girdle, and pelvic girdle muscles. Typical findings include multiple tender points distributed across the body, and a diagnosis can be made after excluding conditions such as polymyalgia rheumatica and chronic fatigue syndrome.

The diagnostic criteria set forth by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 2016 suggest that three conditions must be met for a diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS):

- A widespread pain index (WPI) score of ≥7 and symptom severity scale (SSS) score of ≥5, or a WPI score between 4 and 6 and SSS score of ≥9.

- Current widespread pain affecting at least four out of five body regions, excluding pain in the jaw, chest, and abdomen.

- Symptoms persisting for more than three months.

The diagnosis of FMS is independent of other conditions and does not exclude the presence of other clinical diseases.

Treatment and Prognosis

Due to the unclear etiology and pathophysiological mechanisms, there is no specific treatment for FMS. Management primarily involves a multidisciplinary approach, including appropriate exercise, stress reduction, and symptomatic pain relief.

Pharmacological Treatment

The goal is to block neural triggers and improve psychological symptoms. Antidepressants are the first-line medications and can improve sleep and fatigue, although they are ineffective for pain at tender points. Among them, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as amitriptyline, are the most widely used. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and highly selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are also common choices, particularly when combined with TCAs, as this combination significantly improves sleep, reduces pain and fatigue, and alleviates depressive symptoms. Pregabalin, a second-generation anticonvulsant, was the first medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of FMS. Acetaminophen is effective for some FMS patients, while weak opioids such as tramadol can be used for moderate to severe pain that does not respond to other treatments.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Non-pharmacological approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, hydrotherapy, aerobic exercise, and flexibility training, can also enhance therapeutic outcomes and reduce adverse effects from medications.

FMS is characterized by alternating periods of relapse and remission. However, it does not lead to visceral organ damage, and the prognosis is generally favorable.