Bronchial asthma, commonly known as asthma, is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Clinically, it manifests as recurrent episodes of wheezing, tachypnea, chest tightness, or coughing, which often occur or worsen at night or in the early morning. These symptoms are accompanied by variable expiratory airflow limitation, which fluctuates over time and varies in severity.

Epidemiology

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide, with its prevalence increasing in recent years. Globally, approximately 358 million people are affected by asthma. Asthma-related mortality ranges from 1.6 to 36.7 per 100,000 population, with approximately 350,000 deaths annually worldwide. Most asthma-related deaths are associated with poor long-term control or delayed treatment during exacerbations, and many of these deaths are preventable.

Etiology

Asthma is a complex, polygenic disease with a strong hereditary predisposition. It often clusters in families, with a higher prevalence among close relatives. In recent years, advancements in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revolutionized the identification of asthma susceptibility genes, such as TSLP, ORMDL3, GSDMB, HLA-DQ, and IL-33. However, the development of asthma in individuals with susceptibility genes is heavily influenced by environmental factors. Research into gene-environment interactions is crucial for understanding the genetic mechanisms of asthma.

Environmental Factors

Allergenic factors include:

- Indoor allergens: dust mites, household pets, mold, cockroaches, etc.

- Outdoor allergens: grass pollen, tree pollen, etc.

- Occupational allergens: reactive dyes, certain grains and seeds, proteolytic enzymes used in detergents, brewing, and leather industries, etc.

- Foods: fish, shrimp, eggs, milk, etc.

- Drugs: aspirin, antibiotics, etc.

Non-allergenic factors include air pollution, smoking, exercise, obesity, psychological stress, and anxiety.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of asthma is not yet fully understood but can be summarized as involving airway immune-inflammatory mechanisms, neural regulation, and their interactions.

Mechanisms of Airway Inflammation

Chronic airway inflammation is the result of interactions among various inflammatory cells, airway structural cells, inflammatory mediators, and cytokines. Upon stimulation by allergens, pollutants, or microorganisms, airway epithelial cells release cytokines such as IL-33, IL-25, and TSLP, which activate type 2 helper T cells (Th2) and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2).

On one hand, activated Th2 and ILC2 produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which activate B lymphocytes to synthesize specific IgE. IgE binds to IgE receptors on mast cells and basophils. When allergens re-enter the body, they cross-link with IgE on the cell surface, activating mast cells and basophils to synthesize and release various active mediators. This leads to airway smooth muscle contraction, increased mucus secretion, and inflammatory cell infiltration, producing the clinical symptoms of asthma. This is a typical allergic reaction process.

On the other hand, cytokines secreted by activated Th2 and ILC2 directly activate mast cells, eosinophils, and macrophages, causing their accumulation in the airway. These cells further release inflammatory factors such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, neuropeptides, and eosinophil chemotactic factors. This creates a complex network of interactions among inflammatory cells, airway structural cells, and inflammatory mediators, contributing to the development and progression of chronic airway inflammation.

Recent studies have shown that eosinophils not only act as terminal effector cells in asthma but also play a role in immune regulation. Additionally, Th17 cells are implicated in neutrophil-dominant, steroid-resistant asthma and severe asthma.

Airway Hyperresponsiveness (AHR)

AHR refers to an exaggerated sensitivity of the airways to various stimuli, such as allergens, physical and chemical factors, exercise, or drugs. It manifests as an excessive or premature airway contraction response when exposed to these stimuli. AHR is a hallmark feature of asthma and can be quantified and assessed through bronchial provocation tests. Nearly all symptomatic asthma patients exhibit AHR.

Upon exposure to allergens or other stimuli, inflammatory cells release mediators and cytokines, causing airway epithelial damage and exposure of subepithelial nerve endings, which contribute to chronic airway inflammation and AHR. Individuals with asymptomatic AHR are at significantly increased risk of developing typical asthma symptoms. However, not all individuals with AHR have asthma. Conditions such as long-term smoking, ozone exposure, viral upper respiratory infections, and COPD can also cause AHR, though typically to a lesser degree.

Neural Regulation Mechanisms

Neural factors play a crucial role in asthma pathogenesis. The bronchi are regulated by a complex autonomic nervous system, including adrenergic, cholinergic, and non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) systems.

Asthma patients often exhibit reduced β-adrenergic receptor function and increased cholinergic nerve tone, as evidenced by heightened airway reactivity to histamine and methacholine.

The NANC system releases mediators that either relax airway smooth muscle (e.g., vasoactive intestinal peptide, nitric oxide) or contract it (e.g., substance P, neurokinins). An imbalance between these mediators can result in bronchial smooth muscle contraction.

Additionally, neuropeptides released from sensory nerve endings, such as substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and neurokinin A, contribute to vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and inflammatory exudation, leading to neurogenic inflammation. This inflammation can trigger asthma attacks through local axon reflexes and the release of sensory neuropeptides.

Pathology

Chronic airway inflammation, a hallmark of asthma, is present in all asthma patients. It is characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells such as subepithelial mast cells, eosinophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils in the airway, along with pathological changes including submucosal edema, increased microvascular permeability, bronchial smooth muscle spasm, epithelial ciliary cell shedding, goblet cell hyperplasia, and increased airway secretions. In cases of long-term, recurrent asthma attacks, airway remodeling may occur, including hypertrophy/hyperplasia of bronchial smooth muscle, mucous metaplasia of epithelial cells, subepithelial collagen deposition and fibrosis, vascular proliferation, and thickening of the basement membrane.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

The typical symptom of asthma is episodic expiratory dyspnea accompanied by wheezing, often associated with tachypnea, chest tightness, or coughing. These symptoms can develop within minutes and last for hours to days, alleviating either spontaneously or with bronchodilator treatment. Asthma symptoms vary over time and in severity, with nighttime and early morning exacerbations being hallmark features. Some patients, especially adolescents, experience asthma symptoms triggered by exercise, a condition known as exercise-induced asthma.

Additionally, there are atypical forms of asthma without wheezing. These patients may present with episodic coughing, chest tightness, or other symptoms.

Cough variant asthma (CVA) is asthma with coughing as the sole symptom.

Chest tightness variant asthma (CTVA) is asthma with chest tightness as the sole symptom.

Signs

During an attack, the typical sign is widespread wheezing heard over both lungs, along with prolonged expiratory sounds. In severe asthma attacks, wheezing may diminish or disappear entirely, resulting in a silent lung, which indicates a critical condition. In non-attack periods, physical examination may reveal no abnormalities, so the absence of wheezing does not rule out asthma.

Laboratory and Other Tests

Sputum Eosinophil Count

Most asthma patients exhibit elevated sputum eosinophil counts (>2.5%), which correlate with asthma symptoms. Induced sputum eosinophil count is a useful marker for assessing airway inflammation in asthma and is a sensitive indicator for evaluating the response to corticosteroid therapy.

Peripheral Blood Eosinophil Count

Some asthma patients have elevated peripheral blood eosinophil counts. While this is not diagnostic for asthma, it can help identify eosinophilic asthma phenotypes, guide medication selection, and monitor treatment response.

Pulmonary Function Tests

Ventilation Function Testing

During asthma attacks, patients exhibit obstructive ventilatory dysfunction, characterized by normal or reduced forced vital capacity (FVC), decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), reduced FEV1/FVC ratio, and lower peak expiratory flow (PEF). Residual volume (RV) and the RV/total lung capacity (TLC) ratio are increased. Among these, an FEV1/FVC ratio of <70% is the most important indicator of airflow limitation. These parameters typically improve during remission but may progressively decline in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms.

Bronchial Provocation Test (BPT)

This test measures airway hyperresponsiveness. Commonly used inhaled provocants include methacholine and histamine. Key parameters include FEV1 and PEF. Results are expressed as the cumulative dose (PD20-FEV1) or concentration (PC20-FEV1) of the provocant required to reduce FEV1 by 20%. A reduction of ≥20% is considered positive, indicating airway hyperresponsiveness. BPT is suitable for non-attack periods in patients with an FEV1 ≥70% of the predicted value.

Bronchodilation Test (BDT)

This test assesses the reversibility of airway obstruction. Commonly used bronchodilators include salbutamol and terbutaline. Pulmonary function is re-measured 20 minutes after inhalation of the bronchodilator. An increase in FEV1 of ≥12% and an absolute increase of ≥200 mL compared to pre-treatment values is considered positive, indicating reversible airway obstruction.

Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) and Variability

PEF decreases during asthma attacks. Due to the circadian variation in ventilatory function in asthma, monitoring diurnal and weekly PEF variability aids in diagnosis and disease assessment.

Diurnal variability: Average daily diurnal variability over 7 days >10%.

Weekly variability: {(Highest PEF - Lowest PEF over 2 weeks) / [(Highest PEF + Lowest PEF) × 1/2]} × 100% >20%.

These findings suggest reversible airway changes.

Chest X-ray/CT

During asthma attacks, chest X-rays may show increased lung translucency, indicating hyperinflation. In remission, findings are usually normal. Chest CT may reveal bronchial wall thickening and mucus plugging in some patients.

Specific Allergen Testing

Elevated specific IgE levels in peripheral blood, combined with a detailed history, can help identify causative allergens. While total serum IgE levels have limited diagnostic value for asthma, their elevation can guide the use and dosing of anti-IgE antibody therapy in severe asthma. In vivo allergen tests include skin prick testing and allergen provocation tests.

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

Severe asthma attacks can result in hypoxemia. Hyperventilation may cause reduced PaCO2 and elevated pH, leading to respiratory alkalosis. With worsening disease, both hypoxemia and CO2 retention may occur, resulting in respiratory acidosis. An increase in PaCO2, even within the normal range, compared to previous levels should prompt concern for severe airway obstruction.

Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) Testing

FeNO measurement is a useful marker for assessing asthma control and can help predict and evaluate the response to inhaled corticosteroid therapy.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

Typical clinical symptoms and signs of asthma:

- Recurrent episodes of wheezing and tachypnea, with or without chest tightness or coughing, often occurring at night or early in the morning. These symptoms are frequently triggered by exposure to allergens, cold air, physical or chemical irritants, viral upper respiratory infections, or exercise.

- During attacks or in uncontrolled persistent asthma, scattered or diffuse wheezing sounds can be heard in both lungs, with prolonged expiratory phases.

- These symptoms and signs can be alleviated with treatment or resolve spontaneously.

Objective evidence of variable airflow limitation:

- Positive bronchodilation test.

- Positive bronchial provocation test.

- Average daily diurnal PEF variability >10% or weekly PEF variability >20%.

Asthma can be diagnosed if the above symptoms and signs are present, along with at least one objective indicator of airflow limitation, and other causes of wheezing, tachypnea, chest tightness, and coughing are excluded.

Cough variant asthma (CVA) or chest tightness variant asthma (CTVA):

- These refer to cases where cough or chest tightness is the sole or primary symptom, without wheezing or other typical asthma manifestations. Diagnosis requires at least one objective indicator of variable airflow limitation, exclusion of other causes of cough or chest tightness, and responsiveness to asthma treatment.

Staging and Classification of Asthma Control

Asthma can be categorized into three stages based on clinical presentation: acute exacerbation phase, chronic persistent phase, and clinical control phase.

Acute Exacerbation Phase

This phase is characterized by sudden onset or worsening of symptoms such as wheezing, tachypnea, chest tightness, or coughing, accompanied by reduced expiratory airflow. It is often triggered by exposure to allergens or other stimuli, or by inadequate treatment. The severity of acute exacerbations can vary, with some progressing to life-threatening conditions within minutes. Accurate assessment and timely treatment are crucial.

The severity of acute exacerbations is classified into four levels: mild, moderate, severe, and life-threatening:

- Mild: Tachypnea during walking or climbing stairs, possible anxiety, mild increase in respiratory rate, scattered wheezing sounds, normal pulmonary ventilation function, and normal blood gas analysis.

- Moderate: Tachypnea with mild activity, interrupted speech, occasional anxiety, increased respiratory rate, possible use of accessory muscles (e.g., intercostal retractions), loud and diffuse wheezing, increased heart rate, possible pulsus paradoxus. PEF is 60-80% of the predicted value after bronchodilator use, and oxygen saturation (SaO2) is 91-95%.

- Severe: Tachypnea at rest, sitting upright to breathe, speaking only in single words, frequent anxiety or agitation, profuse sweating, respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, frequent use of accessory muscles, loud and diffuse wheezing, heart rate >120 bpm, significant pulsus paradoxus. PEF is <60% of the predicted value or <100 L/min, with bronchodilator effects lasting <2 hours. PaO2 <60 mmHg, PaCO2 >45 mmHg, SaO2 ≤90%, and normal or decreased pH.

- Life-threatening: Inability to speak, drowsiness or confusion, paradoxical chest-abdominal movement, diminished or absent wheezing, irregular or slow pulse, severe hypoxemia and hypercapnia, and decreased pH.

Chronic Persistent Phase

In this phase, patients do not experience acute exacerbations but may have varying frequencies and severities of symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, or chest tightness over an extended period. Pulmonary ventilation function may also be impaired. At the start of treatment, the severity of chronic persistent asthma can be classified into four levels based on the frequency of daytime and nighttime symptoms and pulmonary function results: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent.

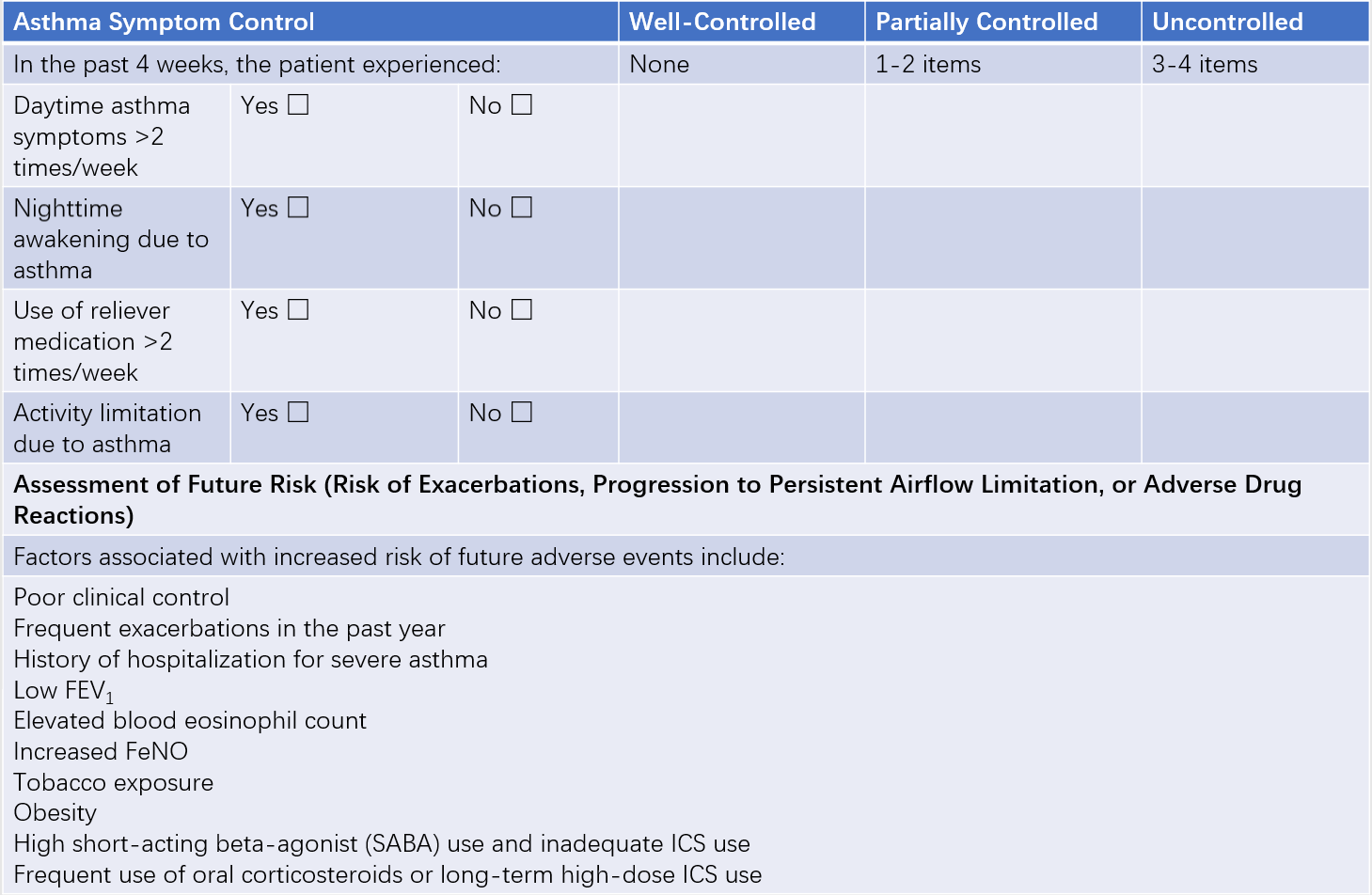

The most widely used method for evaluating chronic persistent asthma severity is the level of asthma control, which includes assessments of current clinical control and future risk. Clinical control is further divided into three levels: well-controlled, partially controlled, and uncontrolled.

Table 1 Classification of asthma control levels

Clinical Control Phase

This phase is characterized by the absence of symptoms such as wheezing, tachypnea, chest tightness, or coughing for more than 4 weeks, no acute exacerbations in the past year, and normal pulmonary function.

Differential Diagnosis

Dyspnea Caused by Left Heart Failure

Symptoms can resemble those of severe asthma, making differentiation challenging. Key points for differentiation: Patients often have a history or signs of hypertension, coronary artery disease, or rheumatic heart disease. Symptoms include sudden onset of dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal coughing (often with pink frothy sputum), widespread moist rales and wheezing in both lungs, left heart enlargement, and tachycardia with a gallop rhythm audible at the apex.

Chest X-rays may show cardiac enlargement and pulmonary congestion. If differentiation is difficult, nebulized β2-agonists or intravenous aminophylline may be used to relieve symptoms, followed by further evaluation. Epinephrine and morphine should be avoided.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD is more common in middle-aged and older individuals, often with a history of long-term smoking or exposure to harmful gases, and a history of chronic cough. Wheezing is persistent and worsens during exacerbations. Physical examination may reveal significantly reduced breath sounds, signs of emphysema, and moist rales in both lungs. Differentiating COPD from asthma in older patients can be particularly challenging. Diagnostic treatment with bronchodilators combined with oral or inhaled corticosteroids may help. If a patient exhibits characteristics of both asthma and COPD, a diagnosis of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) can be established.

Upper Airway Obstruction

Conditions such as central bronchial lung cancer, tracheobronchial tuberculosis, relapsing polychondritis, or foreign body aspiration can cause bronchial narrowing or infection, leading to wheezing or asthma-like dyspnea. Wheezing may be heard on lung examination. Diagnosis can often be established based on history, particularly inspiratory dyspnea, combined with sputum cytology or bacteriology, chest imaging, and bronchoscopy.

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA)

ABPA is characterized by recurrent asthma attacks and the production of brown, sticky mucus plugs or bronchial casts. Sputum eosinophil counts are elevated. Chest CT may reveal cystic or cylindrical bronchiectasis in proximal bronchi. Aspergillus-specific IgE is positive, and total serum IgE levels are significantly elevated.

Complications

Severe asthma attacks may lead to complications such as pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, or atelectasis. Long-term recurrent attacks or infections can result in chronic complications such as COPD, bronchiectasis, and cor pulmonale.

Treatment

Although asthma cannot currently be cured, long-term standardized treatment can enable most patients to achieve good or complete clinical control. The goal of asthma treatment is long-term symptom control and minimizing associated risks, including asthma-related mortality, acute exacerbations, persistent airflow limitation, and treatment side effects. Ideally, patients should be able to live, study, and work like healthy individuals with minimal or no medication at the lowest effective dose.

Reducing Exposure to Risk Factors

For some patients, specific allergens or other nonspecific triggers that cause asthma attacks can be identified. Avoiding these risk factors is one of the most effective methods for preventing and managing asthma.

Drug Classification and Characteristics

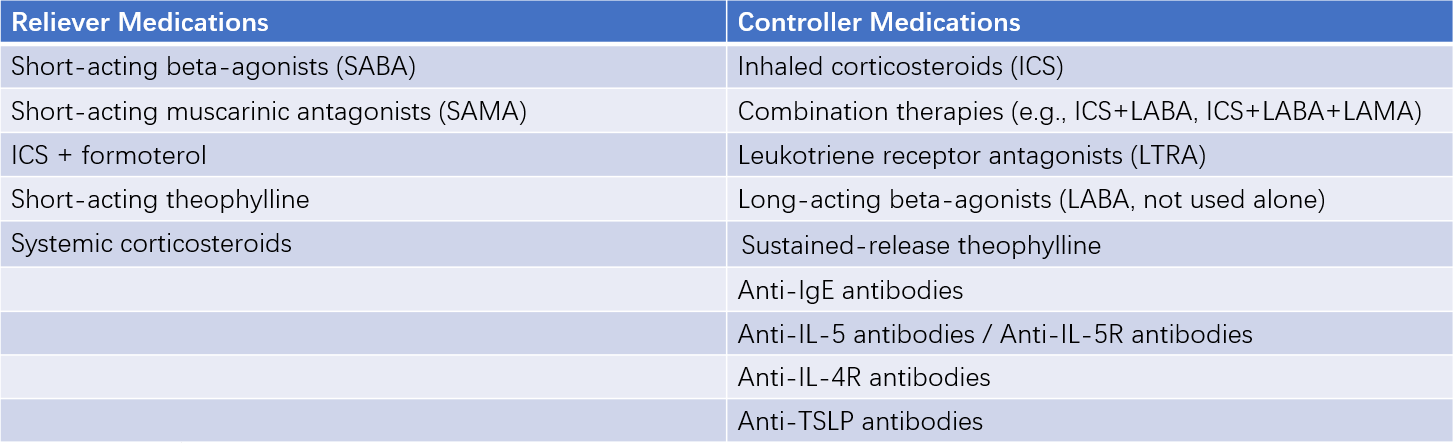

Asthma medications are classified into controller medications and reliever medications:

- Controller medications: These are used long-term to treat chronic airway inflammation and maintain clinical control of asthma. They are also referred to as anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Reliever medications: These are used as needed to quickly relieve bronchospasm and alleviate asthma symptoms. They are also known as bronchodilators.

Table 2 Classification of asthma medications

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are currently the most effective medications for controlling asthma. They work by targeting multiple aspects of airway inflammation, such as inhibiting the accumulation of eosinophils and other inflammatory cells in the airways, suppressing the production of inflammatory factors and mediators, and enhancing the responsiveness of airway smooth muscle β2 receptors. Corticosteroids can be administered via inhalation, orally, or intravenously.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the first-line treatment for long-term asthma management due to their strong local anti-inflammatory effects and minimal systemic side effects. Commonly used ICS include beclomethasone, budesonide, and fluticasone. The dosage of ICS is selected based on the severity of asthma, and regular inhalation for 1-2 weeks or longer is typically required to achieve effectiveness.

Although ICS have few systemic side effects, some patients may experience oral candidiasis or hoarseness. Rinsing the mouth with water after inhalation can reduce local reactions and gastrointestinal absorption. For patients using high doses of ICS (>1,000 μg/day), systemic side effects should be monitored. To minimize side effects associated with high-dose ICS, a combination of low- to medium-dose ICS with long-acting β2 agonists (LABA), leukotriene receptor antagonists, or sustained-release theophylline can be used.

Budesonide and beclomethasone are also available as nebulized suspensions, which can be administered via jet nebulizers powered by compressed air. These formulations have a rapid onset of action and can be used for the treatment of mild to moderate acute asthma exacerbations when combined with short-acting bronchodilators.

Commonly used oral corticosteroids include prednisone and prednisolone, which are suitable for patients who do not respond to ICS or require short-term intensified treatment. The starting dose is typically 30-60 mg/day, which is gradually reduced to ≤10 mg/day once symptoms improve, followed by discontinuation or transition to inhaled corticosteroids. Long-term oral corticosteroid use is not recommended for maintaining asthma control.

In cases of severe or life-threatening asthma exacerbations, intravenous corticosteroids should be administered early. Common options include hydrocortisone sodium succinate (100-400 mg/day) or methylprednisolone (80-160 mg/day). Dexamethasone, due to its longer half-life and higher risk of side effects, should be used with caution.

For patients without steroid dependence, corticosteroids can be discontinued within 3-5 days. For those with steroid dependence, the treatment duration should be appropriately extended, with gradual dose reduction and transition to oral or inhaled corticosteroids for maintenance once symptoms improve.

β2 Agonists

These medications relieve asthma symptoms by stimulating airway β2 receptors, leading to bronchodilation. Β2 agonists are classified into short-acting β2 agonists (SABA), which provide 4-6 hours of relief, and long-acting β2 agonists (LABA), which last 10-12 hours. LABAs can be further divided into rapid-onset (effective within minutes) and slow-onset (effective within 30 minutes) types.

SABAs are available in inhaled, oral, and intravenous formulations, and inhalation is the preferred method of administration. Common SABAs include salbutamol and terbutaline, which are available as metered-dose inhalers (MDI), dry powder inhalers (DPI), and nebulized solutions. Common side effects include palpitations, skeletal muscle tremors, and hypokalemia. SABAs should be used intermittently and as needed, but not as monotherapy. Overuse of SABAs increases the risk of acute asthma exacerbations. When prescribing SABAs as reliever medications, they should be combined with ICS.

LABAs combined with ICS are currently the most commonly used controller medications for asthma. Common LABAs include salmeterol and formoterol. Formoterol is a rapid-onset LABA and can also be used as needed for acute asthma exacerbations. Common ICS/LABA combination inhalers include fluticasone/salmeterol DPI, budesonide/formoterol DPI, and beclomethasone dipropionate/formoterol MDI. It is important to note that LABAs should not be used as monotherapy for asthma.

Leukotriene Modifiers

These medications exert anti-inflammatory effects by regulating leukotriene activity and can also relax bronchial smooth muscles. They are often used as part of combination therapy for moderate to severe asthma, especially in patients with aspirin-sensitive asthma, exercise-induced asthma, or asthma associated with allergic rhinitis. A common leukotriene modifier is montelukast. Side effects are generally mild but may include rash, angioedema, elevated liver enzymes, or neuropsychiatric symptoms, which usually resolve upon discontinuation.

Theophyllines

Theophyllines act by inhibiting phosphodiesterase, increasing intracellular cAMP levels in smooth muscle cells, antagonizing adenosine receptors, enhancing respiratory muscle contractility, and improving airway ciliary clearance. These mechanisms result in bronchodilation and anti-inflammatory effects.

Commonly used oral theophyllines include aminophylline and sustained-release theophylline, with a typical daily dose of 6-10 mg/kg.

The loading dose of intravenous aminophylline is 4-6 mg/kg, administered at a rate not exceeding 0.25 mg/(kg·min). The maintenance dose is 0.6-0.8 mg/(kg·h), with a maximum daily dose generally not exceeding 1.0 g.

Rapid intravenous administration of theophyllines can cause serious side effects, including death. Due to the narrow therapeutic window of theophyllines, blood drug levels should be monitored when possible. The safe and effective concentration range is 6-15 mg/L. Special caution is required in patients with fever, pregnancy, children, or older individuals, as well as those with hepatic, cardiac, or renal dysfunction or hyperthyroidism. Co-administration of drugs such as cimetidine, quinolones, or macrolides can slow the metabolism of theophyllines, necessitating dose adjustments.

Anticholinergic Drugs

Anticholinergic drugs work by blocking postganglionic vagal pathways, reducing vagal tone, which leads to bronchodilation and decreased mucus secretion. However, their bronchodilatory effect is weaker than that of β2 agonists. These drugs are divided into short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA), which last 4-6 hours, and long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), which last up to 24 hours.

Commonly used SAMAs, such as ipratropium bromide, are available in metered-dose inhalers (MDI) and nebulized solutions. SAMA is mainly used for the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations, often in combination with β2 agonists. Side effects may include a bitter taste or dry mouth in some patients.

Commonly used LAMA, such as tiotropium bromide, is a selective M1 and M3 receptor antagonist with stronger and longer-lasting effects (up to 24 hours). LAMA is primarily indicated for patients whose asthma is not well-controlled with medium- or high-dose ICS combined with LABA.

Combination inhalers containing ICS, LABA, and LAMA, such as indacaterol/glycopyrronium/mometasone furoate dry powder inhaler, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol/umeclidinium dry powder inhaler, and beclomethasone/formoterol/glycopyrronium, are convenient options for patients with severe asthma.

Biologic Therapies

Anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies (omalizumab) block the binding of free IgE to IgE receptors on effector cells. They are indicated for patients with severe asthma who have elevated serum IgE levels and remain uncontrolled despite high-dose ICS and LABA therapy.

Anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., mepolizumab) block the action of IL-5, thereby reducing eosinophil levels in the body and treating asthma.

Anti-IL-5 receptor (IL-5R) monoclonal antibodies (e.g., benralizumab) target IL-5Rα on eosinophils, rapidly and directly depleting eosinophils through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).

Anti-IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) monoclonal antibodies (e.g., dupilumab) inhibit the binding of IL-4 and IL-13 to IL-4Rα, blocking the signaling pathway that mediates Th2 and ILC2 activation, inflammatory mediator release, excessive mucus secretion, and eosinophil accumulation.

Anti-TSLP monoclonal antibodies block the binding of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) to its receptor, downregulating the release of type 2 cytokines and suppressing Th2- and ILC2-mediated immune-inflammatory cascades, effectively treating airway inflammation in asthma.

Biologic therapies are primarily recommended as add-on treatments for severe asthma. The choice of biologics should be guided by biomarkers to individualize treatment and predict therapeutic response.

Treatment of Acute Exacerbations

The goal of treating acute exacerbations is to quickly relieve bronchospasm, correct hypoxemia, restore lung function, prevent further deterioration or recurrence, and manage complications.

Mild Exacerbation

For mild exacerbations, a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) can be inhaled using a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), with 1-2 puffs administered every 20 minutes within the first hour. Subsequently, the frequency can be adjusted to 1-2 puffs every 3-4 hours. During SABA use, the dose of the controller medication (inhaled corticosteroid, ICS) is typically increased, with the ICS dose being at least doubled from the baseline dose. If the controller medication consists of budesonide/formoterol (160 μg/4.5 μg), the dose may be increased by 1-2 inhalations, but the total daily dose should not exceed 8 inhalations.

Moderate Exacerbation

For moderate exacerbations, SABA is often administered via nebulization, with continuous nebulization during the first hour. This is typically combined with nebulized short-acting anticholinergic drugs and corticosteroid suspensions. Intravenous theophylline may also be considered.

If the treatment response is insufficient, particularly in cases where the exacerbation occurs despite controller medication use, oral corticosteroids are usually administered as early as possible, along with oxygen therapy.

Severe to Life-threatening Exacerbation

For severe to life-threatening exacerbations, continuous nebulized SABA is often used in combination with nebulized short-acting anticholinergic drugs, corticosteroid suspensions, and intravenous theophylline. Oxygen therapy is also commonly provided.

Intravenous corticosteroids are typically initiated early in treatment, with a transition to oral corticosteroids once the condition is stabilized.

Attention is generally given to maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance and correcting acid-base imbalances. When the pH falls below 7.20 and metabolic acidosis is present, bicarbonate supplementation may be appropriate.

If clinical symptoms and lung function fail to improve or continue to deteriorate despite these treatments, mechanical ventilation is often required. Indications for invasive mechanical ventilation may include respiratory muscle fatigue, PaCO2 ≥ 45 mmHg, and altered consciousness. Preventing respiratory infections and other complications is also considered important.

For all patients experiencing acute exacerbations, an individualized long-term treatment plan should be developed.

Treatment During Chronic Persistent Phase

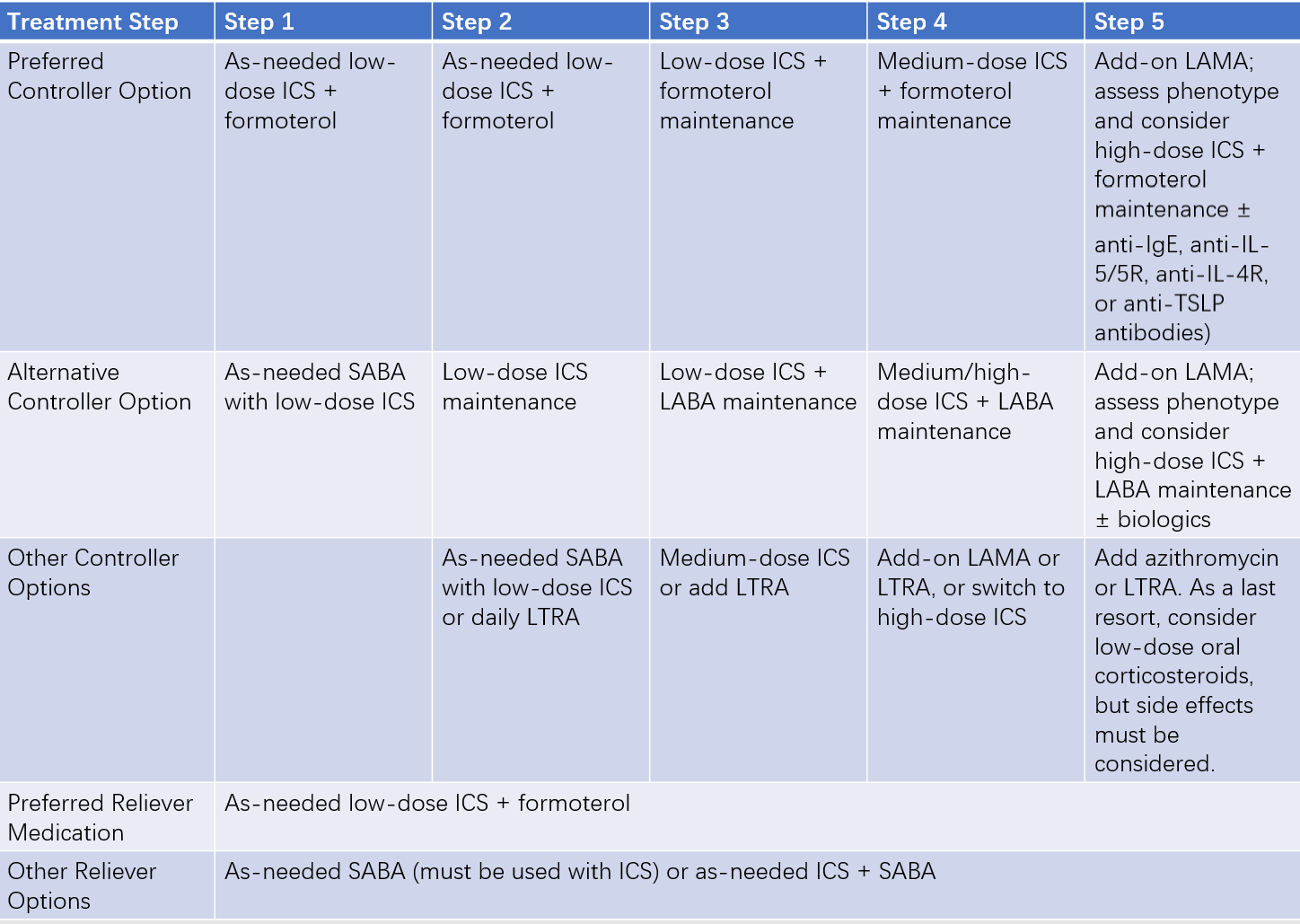

Treatment during the chronic persistent phase should be based on regular evaluation and monitoring of asthma control levels. Adjustments should be made according to the stepwise treatment plan to maintain control.

The long-term asthma treatment plan is divided into five steps. If the current step fails to achieve asthma control, step-up treatment is needed until control is achieved. If asthma symptoms are controlled and lung function remains stable for more than 3 months, step-down treatment can be considered.

Recommended step-down strategy:

- Gradually reduce the steroid dose (oral or inhaled).

- Reduce dosing frequency (e.g., from twice daily to once daily).

- Finally, discontinue controller medications combined with ICS, maintaining the lowest effective ICS dose until discontinuation.

Typically, patients should be followed up 2-4 weeks after the initial diagnosis and then every 1-3 months. In the event of an asthma exacerbation, patients should seek medical attention promptly, with follow-up scheduled within 2 weeks to 1 month after the exacerbation.

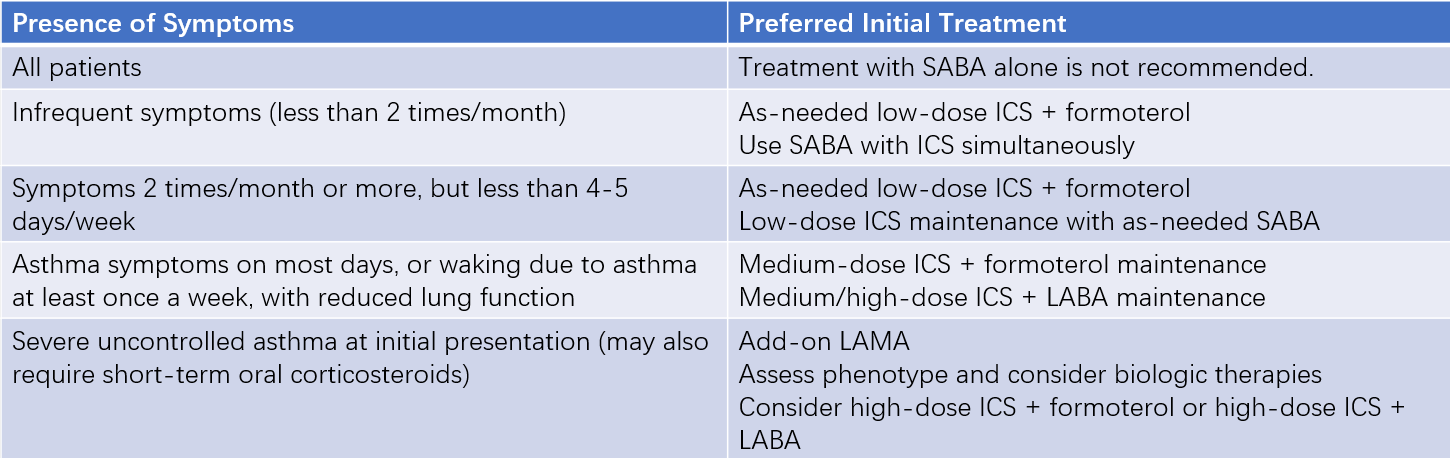

For the initial treatment of adult asthma patients, the appropriate step should be selected based on the patient’s specific condition. If there is uncertainty between two adjacent steps, the higher step can be used to ensure initial treatment success.

Table 3 Long-term (stepwise) asthma treatment plans

Table 4 Initial asthma treatment recommendations for adults and adolescents

Immunotherapy

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is an option for asthma driven primarily by allergic mechanisms. Two methods are currently available: subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). For patients with house dust mite-sensitive asthma (often accompanied by allergic rhinitis), allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) may be added once the disease is well-controlled. This is recommended for patients with mild to moderate asthma, ideally with FEV1 > 70% of the predicted value.

Special Considerations

The treatment principles for cough-variant asthma and chest-tightness-variant asthma are the same as for typical asthma.

Severe asthma refers to asthma that remains uncontrolled or worsens despite high-dose ICS + LABA therapy and good management of triggers. Treatment includes:

- Poor treatment adherence should be ruled out, and triggering factors should be eliminated while comorbidities are managed.

- Based on the assessment of asthma phenotypes, high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) combined with a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), or a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) can be considered. For patients whose symptoms remain uncontrolled or who experience frequent exacerbations, the addition of biologic targeted therapies is recommended.

- Bronchial thermoplasty.

- Adding low-dose oral corticosteroids as a last resort, with careful consideration of their potential side effects.

Asthma Education and Management

Education and management of asthma patients are crucial measures for improving treatment efficacy, reducing relapses, and enhancing patients' quality of life. A long-term prevention and treatment plan should be developed for every newly diagnosed asthma patient. Under the guidance of doctors and specialized nurses, patients should learn to self-manage their condition, including:

- Understanding asthma triggers and methods to avoid them.

- Recognizing early warning signs of asthma attacks and knowing how to respond appropriately.

- Learning to monitor changes in their condition at home and assess their severity.

- Mastering the use of a peak flow meter.

- Keeping an asthma diary consistently.

- Learning simple emergency self-management techniques for asthma attacks.

- Using inhalation devices correctly.

- Knowing when to seek medical attention.

- Collaborating with doctors to develop a plan for preventing relapses and maintaining long-term stability.

Prognosis

With long-term standardized treatment, the clinical control rate for asthma can reach up to 95% in children and 80% in adults. Mild cases are relatively easy to control, whereas severe cases, characterized by significant airway hyperresponsiveness, airway remodeling, or coexisting allergic diseases, are more challenging to manage. Without timely and standardized treatment, repeated acute exacerbations may eventually endanger life, lead to chronic complications causing irreversible loss of lung function, or result in side effects from long-term use of high-dose medications.