Bronchiectasis, first described by Laennec, refers to a group of heterogeneous diseases characterized by abnormal and persistent dilation of the bronchi caused by repeated episodes of suppurative inflammation of the bronchial walls. This condition typically arises after acute or chronic respiratory infections or bronchial obstruction, leading to structural damage of the bronchial walls and thickening of the bronchial lining. Bronchiectasis can be either primary or secondary and is generally classified into two categories: bronchiectasis caused by cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. This section focuses on non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.

In recent years, the incidence of bronchiectasis has shown a decreasing trend due to appropriate treatment of acute and chronic respiratory infections. However, with the widespread use of computed tomography (CT), particularly high-resolution CT (HRCT), bronchiectasis has been increasingly identified in certain patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Bronchiectasis can be classified into congenital bronchiectasis and acquired bronchiectasis.

Congenital bronchiectasis is rare and may occur without a clear cause. Diffuse bronchiectasis often develops in individuals with genetic, immune, or anatomical defects, such as cystic fibrosis, ciliary dyskinesia, or severe α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Focal bronchiectasis can result from untreated pneumonia or airway obstruction caused by foreign bodies, tumors, external compression, or anatomical displacement following lobectomy.

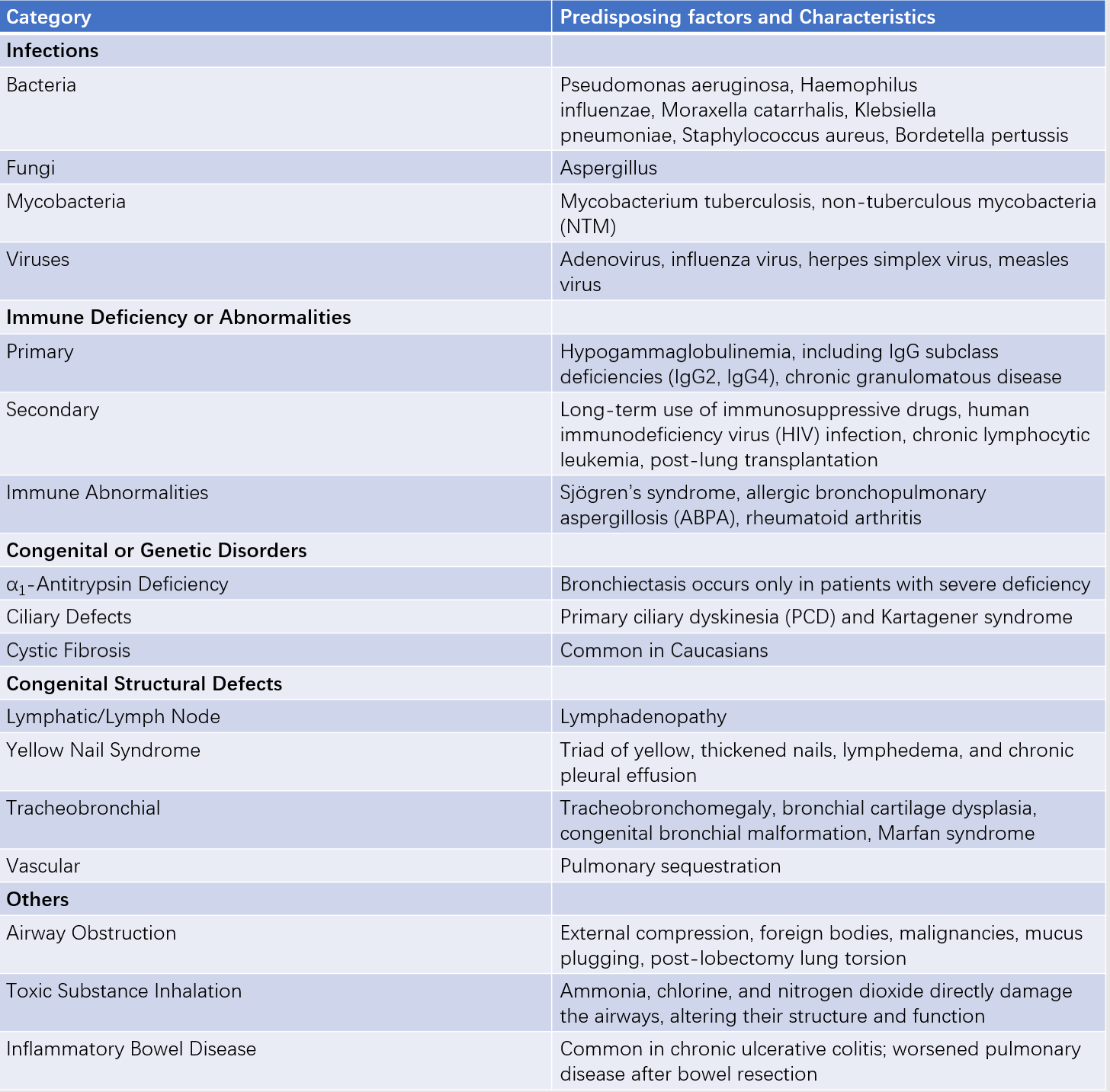

Table 1 Predisposing factors of bronchiectasis

The vicious cycle hypothesis is commonly used to explain the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Chronic bronchial infections caused by various triggers lead to airway inflammation, resulting in excessive mucus secretion, impaired mucus clearance, bacterial colonization, and proliferation. This, in turn, causes structural damage to the airways, further declining lung function and promoting recurrent lung infections.

These factors interact with each other. For example, structural damage to the airways can impair drainage, facilitating bacterial colonization and growth. In patients with bronchiectasis, a vicious cycle of interactions exists, and effective treatment requires breaking or reversing this cycle at multiple points. This includes promoting mucus drainage and clearance, reducing bacterial colonization and infections, enhancing airway defenses, improving airway inflammation, preventing acute exacerbations, and improving lung function, along with partial airway remodeling.

The disease damages the host's airway clearance and defense mechanisms, making infections and inflammation more likely.

Acquired bronchiectasis is often secondary to bacterial, tuberculosis/non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM), viral, or fungal infections. Repeated bacterial infections can lead to progressive airway enlargement filled with inflammatory mediators and pathogens, resulting in scarring and distortion.

The bronchial walls thicken due to edema, inflammation, and neovascularization. Destruction of the surrounding interstitial tissue and alveoli leads to fibrosis, emphysema, or both. Patients with bronchiectasis combined with emphysema have a worse prognosis, with significantly reduced 5-year survival rates. Patients with colonization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa show more rapid lung function decline.

Screening for bronchiectasis should be considered in the following high-risk populations:

- Patients with chronic cough and expectoration, especially those with purulent sputum or hemoptysis.

- COPD patients with frequent acute exacerbations (≥2 times/year), severe or poorly controlled asthma, and a history of sputum culture positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, rheumatic diseases, or other connective tissue diseases who present with chronic cough, expectoration, or recurrent pulmonary infections.

- Patients with a history of HIV infection, solid organ transplantation, or immunosuppressive therapy who develop chronic cough and sputum production.

Pathology and Pathophysiology

Bronchiectasis is typically characterized by destruction and inflammatory changes in the walls of segmental or subsegmental bronchi. The affected bronchial walls show structural damage, including destruction of cartilage, muscle, and elastic tissue, which are replaced by fibrous tissue. This leads to three distinct types of bronchiectasis:

- Cylindrical bronchiectasis: The bronchi are uniformly dilated and abruptly narrow at a certain point, with distal small airways often obstructed by secretions.

- Saccular bronchiectasis: The dilated bronchi appear as cystic structures, and the blind ends of the bronchi form indistinct cystic structures.

- Varicose bronchiectasis: The bronchi exhibit irregular or beaded dilation.

Microscopically, inflammation and fibrosis of the bronchial walls, bronchial wall ulceration, squamous metaplasia, and mucus gland hyperplasia can be observed.

The adjacent lung parenchyma may also show fibrosis, emphysema, bronchopneumonia, and atelectasis. Inflammation can lead to increased vascularization of the bronchial walls, with corresponding bronchial arterial dilation and anastomoses between bronchial and pulmonary arteries.

Bronchiectasis is one of the suppurative diseases in respiratory medicine. Chronic airway inflammation caused by various pathogenic factors leads to increased airway secretions, impaired airway clearance, mucus accumulation, and airway obstruction. This increases the likelihood of microbial colonization, proliferation, and infection. Repeated bacterial infections exacerbate airway inflammation, causing further damage and thickening of the airway walls, which in turn reduces the ability to clear mucus.

Approximately 50% of patients with bronchiectasis exhibit obstructive ventilatory dysfunction, while restrictive ventilatory dysfunction is even more common.

Clinical Manifestations

Bronchiectasis can be divided into two phases: the stable phase and the acute exacerbation phase.

Stable Phase

The primary symptoms include persistent or recurrent cough, expectoration, or purulent sputum. The sputum may be mucous, mucopurulent, or purulent, often yellowish green in color, and may separate into layers when collected (foam on the top, cloudy mucus in the middle, and purulent components or necrotic tissue at the bottom). Onset is often insidious without obvious triggers, and symptoms may be absent or mild.

Acute Exacerbation Phase

During acute infections, patients may experience worsening cough and increased production of purulent sputum, with or without pneumonia. Hemoptysis occurs in 50-70% of cases, and massive hemoptysis is often caused by erosion of small arteries or rupture of newly formed blood vessels. In some cases, recurrent hemoptysis may be the sole symptom, termed dry bronchiectasis. Dyspnea and wheezing often indicate extensive bronchiectasis or underlying COPD.

On physical examination, moist rales (crackles) and dry rales (wheezes) may be heard. Severe cases, especially those with chronic hypoxia, chronic cor pulmonale, and right heart failure, may present with clubbing of fingers or toes and signs of right heart failure.

According to the British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines, acute exacerbation is defined as the worsening of at least three of the following six symptoms within 48 hours, requiring urgent management:

- Increased cough severity

- Increased sputum volume

- Increased purulence of sputum

- Worsening dyspnea or reduced exercise tolerance

- Fatigue or malaise

- Hemoptysis

Laboratory and Other Auxiliary Examinations

Key diagnostic tools include chest X-ray and high-resolution CT (HRCT) of the chest. Laboratory tests include complete blood count, inflammatory markers (e.g., C-reactive protein), immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM), microbiological tests, arterial blood gas analysis, and pulmonary function tests. Additional tests may include sinus CT, serum IgE, specific IgE, Aspergillus skin tests, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, cellular immune function tests, and evaluations for cystic fibrosis (CF) or primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). Bronchoscopy may also be performed when necessary.

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray

Severe bronchiectasis may show the coarse reticular sign. Airway dilation in cystic bronchiectasis may appear as prominent cystic cavities, sometimes with air-fluid levels. When no air-fluid level is present, it may be challenging to distinguish from bullous emphysema or severe interstitial lung disease with honeycombing.

Figure 1 Chest X-ray findings of bronchiectasis

High-resolution CT (HRCT)

HRCT provides clear cross-sectional images of dilated bronchi and is non-invasive, repeatable, and well-tolerated. It is now the primary diagnostic method for bronchiectasis, particularly with slice thickness ≤1 mm. In healthy individuals, the bronchial-to-adjacent pulmonary artery diameter ratio is 0.75 on the left and 0.72 on the right. In bronchiectasis, this ratio is often >1. Bronchi may exhibit cylindrical or cystic changes, airway wall thickening (with inner diameter <80% of outer diameter), mucus plugging, tree-in-bud sign, and mosaic attenuation or air trapping on expiratory scans.

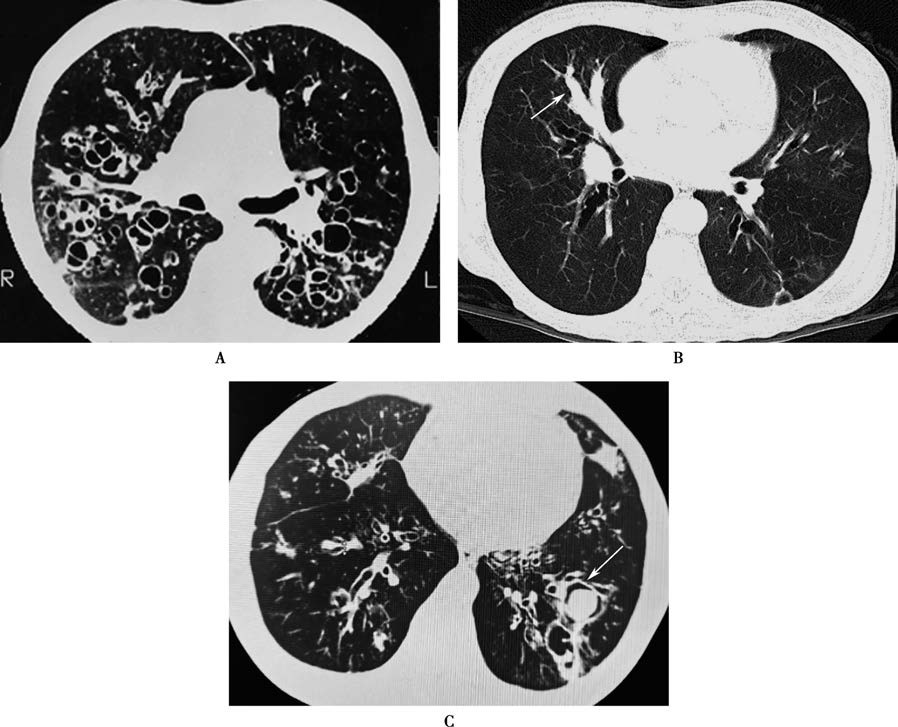

Figure 2 CT findings of bronchiectasis

When CT slices are parallel to the bronchi, dilated airways may appear as tram-track or beaded patterns.

When CT slices are perpendicular to the bronchi, dilated airways and adjacent pulmonary arteries form a signet-ring sign.

Multiple cystically dilated bronchi in close proximity may appear as a honeycomb or coarse reticular pattern.

Some patients with Aspergillus infection may develop aspergilloma.

Bronchography, previously used for definitive diagnosis of bronchiectasis, is an invasive procedure that has been replaced by HRCT.

Laboratory Tests

Complete Blood Count and Inflammatory Markers

During acute exacerbations caused by bacterial infections, white blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels may be elevated.

Serum Immunoglobulins

Patients with immune deficiencies may exhibit reduced levels of serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM).

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

It is used to assess for hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia.

Microbiological Tests

Collection of qualified sputum samples for smear staining, bacterial culture, and drug susceptibility testing is essential. When acid-fast bacilli are identified in sputum, further testing is needed to differentiate Mycobacterium tuberculosis from non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).

Etiological Tests

Additional tests may include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. For suspected allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), serum IgE levels, Aspergillus skin tests, and precipitating antibodies to Aspergillus may be performed.

For patients with early-onset disease, chronic sinusitis or otitis media, or dextrocardia, PCD should be suspected. Exhaled nasal nitric oxide measurement may be used for screening, followed by ciliary ultrastructure examination via electron microscopy and genetic testing if necessary.

Other Examinations

Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy

In cases of focal bronchiectasis involving segmental or larger bronchi, bronchoscopy may reveal craterlike changes. Bronchoscopy can also be used to collect samples for microbiological and pathological diagnosis. It helps identify the site of hemorrhage, dilation, or obstruction. Bronchoalveolar lavage can be performed to obtain specimens for smears, microbiological, and cytological analyses, aiding in diagnosis and treatment.

Pulmonary Function Tests

Some patients may exhibit restrictive, obstructive, or mixed ventilatory dysfunction.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bronchiectasis can be established based on a history of recurrent purulent sputum production, hemoptysis, and prior respiratory infections that predispose to bronchiectasis, along with abnormal imaging findings of bronchial dilation on high-resolution CT. For confirmed cases, a thorough medical history should be obtained, respiratory symptoms should be assessed, and relevant tests should be performed to identify the underlying cause.

Assessment

Initial Evaluation after Diagnosis

Sputum examination includes smear tests (for fungi and acid-fast bacilli) and sputum culture with drug susceptibility testing, both at initial diagnosis and periodically.

Follow-up chest CT is recommended in cases of pulmonary cavitation, unexplained hemoptysis or blood-streaked sputum, poor treatment response, or recurrent acute exacerbations.

Pulmonary function tests are used to assess disease progression and guide pharmacological treatment.

Arterial blood gas analysis is used to determine the presence of hypoxemia and/or CO2 retention.

Laboratory tests are to evaluate the inflammatory response, immune status, and co-infections with other pathogens.

Assessment of Disease Severity and Prognosis

Due to the heterogeneity of bronchiectasis patients, with significant variations in imaging findings, pulmonary function, and clinical symptoms, disease severity is assessed comprehensively using clinical symptoms, physical signs, imaging studies, pulmonary function tests, and laboratory results.

Bronchiectasis severity index (BSI) is commonly used to predict disease progression, hospitalization, and mortality risk.

Total score:

- 0-4: Mild

- 5-8: Moderate

- ≥9: Severe

E-FACED score is primarily used to predict future acute exacerbations and hospitalization.

Total score:

- 0-3: Mild

- 4-6: Moderate

- 7-9: Severe

Differential Diagnosis

Bronchiectasis should be differentiated from the following conditions: chronic bronchitis, lung abscess, pulmonary tuberculosis, congenital pulmonary cysts, diffuse panbronchiolitis, and bronchogenic carcinoma. A detailed history, clinical presentation, and characteristic findings from imaging, fiberoptic bronchoscopy, and bronchography can help make an accurate differential diagnosis.

Chronic Bronchitis

It typically occurs in middle-aged or older patients. Symptoms are more pronounced during winter and spring, with significant cough and sputum production. Sputum is usually white and mucoid, though purulent sputum may occur during acute infections. There is no history of recurrent hemoptysis. Scattered dry and moist rales may be heard on auscultation.

Lung Abscess

It presents with acute onset with high fever, cough, and production of large amounts of foul-smelling purulent sputum. Chest X-ray shows localized dense inflammatory opacities with cavitation and air-fluid levels.

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

It often presents with low-grade fever, diaphoresis, fatigue, and weight loss (tuberculous intoxication symptoms). Dry and moist rales are usually localized to the upper lungs. Chest X-ray and sputum tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis can confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital Pulmonary Cysts

Chest X-ray shows multiple well-defined round or oval opacities with thin walls and no surrounding inflammatory infiltration. Chest CT and bronchography can aid in diagnosis.

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

Chronic cough, sputum production, exertional dyspnea, and chronic sinusitis are common. Chest X-ray and CT show diffuse small nodular opacities. It responds well to macrolide antibiotics.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

It typically occurs in patients over 40 years old. Symptoms may include cough, sputum production, chest pain, and blood-streaked sputum. Massive hemoptysis is rare. Imaging studies, sputum cytology, and bronchoscopy can help confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment of Underlying Diseases

For patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and bronchiectasis, anti-tuberculosis therapy should be initiated promptly. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy can be used for patients with hypogammaglobulinemia.

Infection Control

For bronchiectasis patients showing signs of acute infection, such as increased sputum volume and purulence, antimicrobial therapy is required. Before initiating antibiotics during an acute exacerbation, sputum cultures should be routinely performed, and antibiotic selection should be guided by culture and sensitivity results. However, empirical antibiotic therapy should begin immediately while awaiting culture results.

For patients without risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, empiric antibiotics targeting Haemophilus influenzae should be used. Options include:

- Ampicillin/sulbactam

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate

- Second-generation cephalosporins

- Third-generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime)

- Respiratory fluoroquinolones (e.g., moxifloxacin, levofloxacin)

For patients with risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (e.g., at least two of the following: recent hospitalization, ≥4 antibiotic courses per year or antibiotic use in the last 3 months, severe airflow obstruction [FEV1 <30% predicted], or daily prednisone use >10 mg in the past 2 weeks), antibiotics with anti-pseudomonal activity should be selected. Options include:

- Anti-pseudomonal β-lactams (e.g., ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam)

- Carbapenems (e.g., imipenem, meropenem)

- Aminoglycosides

- Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin)

These may be used as monotherapy or in combination.

For patients with chronic purulent sputum, long-term antibiotic therapy may be considered, such as oral amoxicillin, inhaled aminoglycosides, or intermittent and rotational use of a single antibiotic to enhance pathogen clearance from the lower respiratory tract.

For patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg) combined with antifungal agents (e.g., itraconazole) are typically required for prolonged treatment.

For patients with pulmonary cavities, particularly smooth-walled cavities with or without a tree-in-bud pattern, non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infection should be considered. Diagnosis can be made using sputum acid-fast staining, culture, and molecular testing.

NTM infection may coexist with tuberculosis, presenting with pulmonary cavities or nodules, exudative and proliferative changes, and low-grade fever or diaphoresis. Close monitoring of these clinical features during follow-up is necessary.

Bronchiectasis patients are also prone to Aspergillus colonization or infection, which may manifest as aspergillomas within the airways, chronic fibrocavitary changes, or acute/subacute invasive infections. Invasive Aspergillus infections are typically treated with voriconazole.

Long-term Antibiotic Therapy

Macrolides (e.g., azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin) have immunomodulatory effects and can reduce the frequency of acute exacerbations when used long-term (up to one year), provided no hepatic or renal dysfunction, QT interval prolongation, or significant hearing impairment is present. Monitoring of liver and kidney function, ECG, and hearing is required during treatment.

Inhaled antibiotics such as tobramycin can effectively clear colonized pathogens and reduce acute exacerbations. While already in clinical use, the optimal treatment duration remains under investigation.

Pathogen Eradication Therapy

For patients with newly isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa and disease progression, studies suggest a two-week course of oral ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily), followed by three months of inhaled tobramycin.

For patients with NTM infection, treatment depends on the severity of the infection, presence of hemoptysis or cavities, and disease progression.

If NTM colonization is suspected, or the lesions are localized and mild, treatment may not be necessary.

If NTM is contributing to disease progression or poses a high risk, a combination of at least three drugs may be used for up to two years. However, adverse effects often limit patient tolerance for such prolonged therapy.

Improvement of Airflow Limitation

Routine pulmonary function monitoring is recommended, especially for patients with obstructive ventilatory dysfunction. Long-acting bronchodilators (e.g., long-acting β2-agonists, long-acting anticholinergics, inhaled corticosteroids combined with long-acting β2-agonists) can improve airflow limitation and facilitate secretion clearance. These treatments are particularly effective for patients with airway hyperresponsiveness and reversible airflow limitation. However, due to a lack of robust evidence, there are no standard recommendations for the routine use of bronchodilators in bronchiectasis.

Airway Secretion Clearance

This includes physical methods and mucolytic agents.

Physical methods:

- Postural drainage: Head-down position with elevated pelvis, combined with chest percussion or vibration to assist sputum clearance.

- Nebulized inhalation of normal saline, hypertonic saline (short-term), or mucolytics (e.g., N-acetylcysteine) can help dilute and remove sputum.

- Other methods include chest wall oscillation, positive pressure ventilation, and active breathing exercises.

Medications include mucolytics, expectorants, and antioxidants. N-acetylcysteine has strong mucolytic and antioxidant properties.

Immunomodulators

Medications that enhance respiratory immunity, such as bacterial lysates, can reduce acute exacerbations. Long-term use of macrolides (e.g., azithromycin, clarithromycin) in some patients can also reduce exacerbations and improve symptoms. However, long-term antibiotic use may lead to side effects, including cardiovascular issues, hearing impairment, liver dysfunction, and bacterial resistance.

Hemoptysis Management

For mild hemoptysis, symptomatic treatment or oral medications such as carbazochrome or carboxylic acid sodium can be used.

For moderate hemoptysis, intravenous vasopressin or phentolamine may be administered.

For massive hemoptysis, if medical treatment fails, interventional embolization or surgical treatment may be considered. Vasopressin use requires monitoring for hyponatremia.

Surgical Treatment

For localized bronchiectasis with recurrent symptoms despite adequate medical therapy, surgical resection of the affected lung tissue may be considered.

For massive hemoptysis originating from hypertrophic bronchial arteries, if conservative measures (e.g., rest and antibiotics) fail, localized disease may be treated surgically. Otherwise, bronchial artery embolization is an option.

In cases of severe disability despite maximal medical therapy, lung transplantation may be considered for eligible patients.

Prevention

Vaccinations against pneumococcus and influenza can help prevent or reduce acute exacerbations. COVID-19 vaccination can reduce disease severity and mortality. Immunomodulators may help alleviate symptoms and reduce exacerbations. Smoking cessation is essential. Rehabilitation exercises can help maintain lung function.

Prognosis

The prognosis of bronchiectasis depends on the extent of bronchial involvement and the presence of complications. Patients with localized bronchiectasis can achieve improved quality of life and prolonged survival with active treatment. However, extensive bronchiectasis may lead to impaired lung function, respiratory failure, and death. Massive hemoptysis can also significantly worsen the prognosis. Patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization, pulmonary parenchymal damage (e.g., emphysema, bullae), or coexisting COPD generally have a poorer prognosis. Bronchiectasis in COPD patients is associated with increased mortality.