Unstable angina (UA) and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) are collectively referred to as non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). While UA and NSTEMI share similar causes and clinical manifestations, the degree of myocardial ischemia differs. UA involves new-onset myocardial ischemia (including ischemia at rest) without myocardial necrosis, whereas NSTEMI is characterized by more severe ischemia, accompanied by myocardial injury and elevated biomarkers of myocardial necrosis. If UA is not treated promptly and effectively, it is highly likely to progress to myocardial infarction.

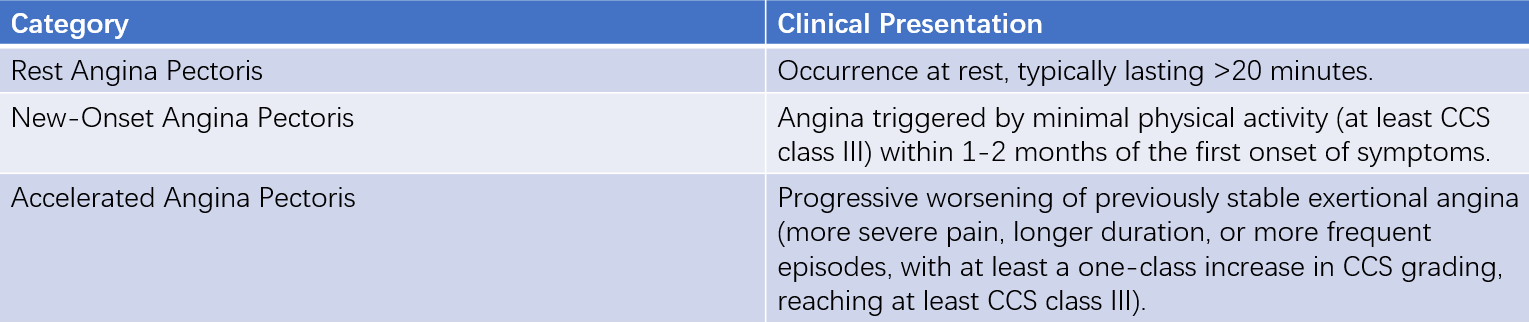

UA does not exhibit the characteristic ECG dynamic changes seen in STEMI. Based on clinical presentation, UA can be divided into three types.

Table 1 Three clinical manifestations of unstable angina

In a small subset of UA patients, angina attacks have clear triggering factors:

- Increased myocardial oxygen demand, such as infection, hyperthyroidism, and arrhythmias

- Reduced coronary blood flow, such as hypotension

- Decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, such as anemia or hypoxemia

These situations are referred to as secondary UA. A special type of UA is variant angina pectoris, which is characterized by rest angina and transient ST-segment elevation on ECG. The underlying mechanism of variant angina is coronary artery spasm.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The primary pathological mechanism of UA/NSTEMI involves unstable atherosclerotic plaque rupture, erosion, or ulceration, leading to platelet aggregation, thrombus formation, coronary artery spasm, and microvascular embolism. These events result in acute or subacute reductions in myocardial oxygen supply and worsening ischemia. While angina may be triggered by physical exertion, the chest pain often does not immediately resolve after cessation of activity.

In NSTEMI, severe and prolonged myocardial ischemia often leads to myocardial necrosis, with pathological findings showing focal or subendocardial myocardial infarction.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

The nature of chest discomfort in UA is similar to that of typical stable angina, but it is more severe, lasts longer (up to tens of minutes), and can occur even at rest. The following clinical features can aid in diagnosing UA:

- A sudden or sustained decrease in the threshold for physical activity that triggers angina

- Increased frequency, severity, and duration of angina episodes

- The occurrence of rest or nocturnal angina

- Chest pain radiating to new locations

- Angina attacks accompanied by new associated symptoms, such as perspiration, nausea, emesis, palpitations, and dyspnea

Routine rest or sublingual nitroglycerin administration may only provide temporary or incomplete relief. However, atypical symptoms are also common, particularly in older, female, and diabetic patients.

Signs

Physical examination may reveal transient third or fourth heart sounds, as well as transient systolic murmurs caused by mitral regurgitation.

Laboratory and Auxiliary Examinations

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

For patients with acute chest pain, an ECG should be recorded within 10 minutes of the first medical contact (FMC). ECG not only aids in diagnosis but also provides prognostic information based on the extent and severity of abnormalities. An ECG recorded during symptoms is particularly valuable, and comparison with previous ECGs can enhance diagnostic accuracy. Most patients exhibit transient changes in the ST segment and T wave (flattening or inversion) during chest pain episodes. Dynamic ST-segment changes (elevation or depression ≥0.1 mV) are indicative of severe coronary artery disease and may predict acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or sudden cardiac death. Less commonly, inverted U waves may be observed.

Typically, these dynamic ECG changes resolve completely or partially after angina subsides. If ECG changes persist for more than 12 hours, NSTEMI should be considered. In patients with a typical history of stable angina or a confirmed history of coronary artery disease, UA can be diagnosed based on clinical presentation even in the absence of ECG changes.

Continuous ECG Monitoring

Transient acute myocardial ischemia does not always manifest as chest pain; ischemia may occur even before chest pain develops. Continuous ECG monitoring can detect ST-segment changes during asymptomatic episodes or anginal attacks. Continuous 24-hour ECG monitoring reveals that 85-90% of myocardial ischemic episodes may occur without accompanying chest pain.

Coronary Angiography and Other Invasive Examinations

Coronary angiography provides detailed vascular information, enabling definitive diagnosis, guiding treatment, and assessing prognosis. Patients with UA superimposed on long-standing stable angina often have multivessel coronary artery disease, whereas those with new-onset rest angina may have single-vessel disease. In UA patients with normal or non-obstructive findings on coronary angiography, chest pain may be due to coronary spasm, spontaneous dissection, spontaneous thrombus dissolution, or microvascular perfusion abnormalities. Misdiagnosis is also a possibility.

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can provide highly accurate intravascular imaging, including information on plaque distribution, characteristics, size, rupture, and thrombus formation.

Myocardial Injury Biomarkers

Cardiac troponins (cTn) T and I are more sensitive and reliable than conventional markers such as CK and CK-MB. If cTn levels exceed the 99th percentile of the normal reference range within 24 hours of symptom onset, NSTEMI should be considered. High-sensitivity cTn assays improve sensitivity, and if initial levels are normal, repeated testing in 1-2 hours can help assess dynamic changes and confirm myocardial injury. The diagnosis of UA primarily relies on clinical presentation and dynamic ST-T changes on ECG during episodes. Positive cTn indicates minor myocardial injury, which is associated with a worse prognosis compared to cTn-negative patients.

Other Examinations

Chest x-rays, echocardiography, and radionuclide imaging findings are similar to those in stable angina but may have a higher rate of positive findings.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The preliminary diagnosis of UA/NSTEMI is based on typical anginal symptoms, ischemic ECG changes (new-onset or transient ST-segment depression ≥0.1 mV or T-wave inversion ≥0.2 mV), and myocardial injury biomarkers. For patients with atypical symptoms and stable conditions where the diagnosis is unclear, stress ECG, stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion imaging, or coronary angiography can be performed before discharge. Coronary angiography is particularly important for determining treatment strategies.

Although the pathogenesis of UA/NSTEMI is similar to that of STEMI, the treatment principles differ, necessitating differential diagnosis.

Classification and Risk Stratification

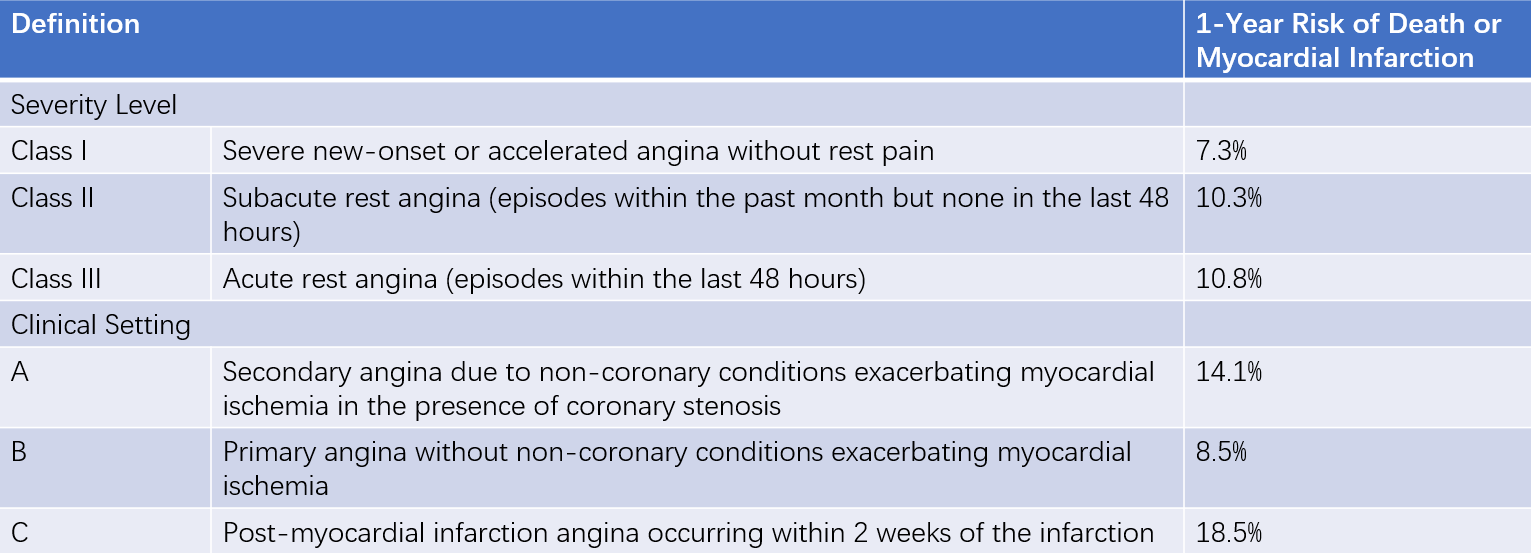

The clinical severity of UA/NSTEMI varies widely, primarily due to differences in the extent and severity of underlying coronary artery disease, as well as the risk of acute thrombosis (progression to STEMI). Braunwald proposed a classification system for UA based on the characteristics of angina and underlying causes (Braunwald classification).

Table 2 Severity grade of unstable angina (Braunwald classification)

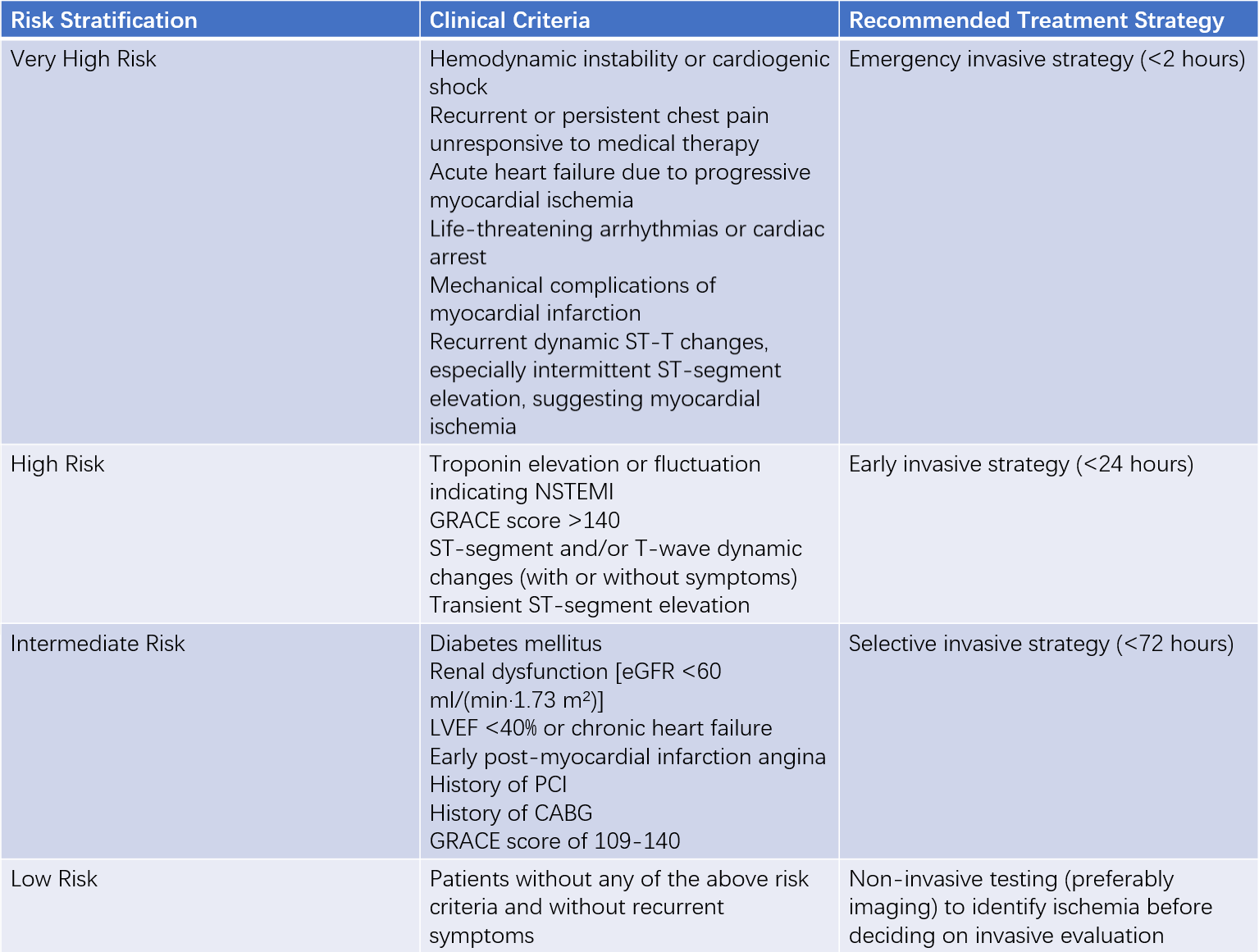

Risk stratification is a critical reference for selecting individualized treatment strategies, particularly the timing of invasive interventions. The GRACE risk model, which includes parameters such as age, history of congestive heart failure, history of myocardial infarction, resting heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, ST-segment deviation on ECG, elevated myocardial injury biomarkers, and whether revascularization is performed, is widely used for risk assessment in UA/NSTEMI.

Table 3 Risk stratification and treatment recommendations for unstable angina or NSTEMI

The GRACE risk score, calculated within 24 hours of admission, can estimate the risk of in-hospital mortality:

- High risk: GRACE score >140, in-hospital mortality risk >3%

- Intermediate risk: GRACE score 109-140, in-hospital mortality risk 1-3%

- Low risk: GRACE score ≤108, in-hospital mortality risk <1%

Treatment

Treatment Principles

The treatment of UA/NSTEMI has two main objectives:

- Immediate relief of ischemic symptoms

- Prevention of serious adverse outcomes (e.g., death, myocardial infarction, or reinfarction)

Treatment includes anti-ischemic therapy, antithrombotic therapy, and invasive treatment based on risk stratification.

The first critical step in managing suspected UA patients is conducting appropriate evaluations in the emergency department, triaging patients to the appropriate level of care, and initiating antithrombotic and anti-ischemic therapy immediately. Low-risk patients may undergo an exercise stress test after emergency treatment and observation; if the results are negative, they can be discharged with continued medical therapy. Most UA patients require inpatient treatment. Patients with progressive ischemia, poor response to initial medical therapy, or hemodynamic instability should be admitted to a cardiac care unit (CCU) for intensive monitoring and treatment.

General Management

Patients should be placed on immediate bed rest, reassured to alleviate anxiety, and kept in a calm environment. Mild sedatives or anxiolytic medications may be used. Approximately half of patients experience relief or alleviation of angina through these measures. For patients with cyanosis, dyspnea, or other high-risk features, supplemental oxygen should be provided, and oxygen saturation (SaO2) should be maintained above 90%. Additionally, any conditions that may increase myocardial oxygen demand should be actively managed.

Pharmacological Therapy

Anti-Ischemic Therapy

The primary goal is to reduce myocardial oxygen demand (e.g., by slowing heart rate or decreasing left ventricular contractility) or to dilate coronary arteries to relieve angina.

During angina episodes, sublingual nitroglycerin (0.5 mg) can be administered. If needed, it can be repeated every 3-5 minutes, up to three doses. If symptoms persist, intravenous nitroglycerin or isosorbide dinitrate may be used.

Intravenous nitroglycerin is initiated at 5-10 μg/min and titrated every 5-10 minutes by increments of 10 μg/min until symptoms resolve or significant side effects occur (e.g., headache or hypotension). The maximum recommended dose is 200 μg/min.

Intravenous nitroglycerin should be transitioned to oral formulations 12-24 hours after symptom resolution. However, tolerance to intravenous nitroglycerin may develop within 24-48 hours of continuous use. Common oral nitrate medications include isosorbide dinitrate and isosorbide mononitrate.

Beta-blockers not only alleviate symptoms but also improve short- and long-term outcomes. They should be initiated as early as possible in all patients without contraindications. High-risk patients may start with intravenous beta-blockers before transitioning to oral therapy, while moderate- to low-risk patients can begin with oral beta-blockers.

β1 selective agents are preferred. Esmolol, a short-acting beta-blocker, can be administered intravenously and is safe and effective even in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Its effects dissipate within 20 minutes of discontinuation.

Oral beta-blocker doses should be individualized to maintain a resting heart rate of 50-60 beats per minute. Beta-blockers are not recommended as monotherapy for coronary artery spasm.

Long-acting calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be used in patients whose ischemic symptoms are not controlled by adequate doses of beta-blockers and nitrates. For patients with vasospastic angina, CCBs are the first-line treatment.

Ivabradine is an alternative for patients with contraindications to beta-blockers or CCBs who require heart rate reduction.

Antiplatelet Therapy

The selection and duration of antiplatelet therapy should be individualized based on patient tolerance, and the dynamic assessment of hemorrhage and ischemic risks.

Aspirin with a loading dose of 150-300 mg (for patients not previously on aspirin) is recommended, followed by a maintenance dose of 75-100 mg daily for long-term use.

For patients at risk of hemorrhage or gastrointestinal damage, indobufen may be considered as an alternative (loading dose: 200 mg; maintenance dose: 100 mg twice daily, long-term use).

Ticagrelor, a reversible ADP receptor inhibitor with faster onset and stronger effect, is the preferred P2Y12 receptor antagonist for UA/NSTEMI. It is initiated with a loading dose of 180 mg, followed by a maintenance dose of 90 mg twice daily. Rare but serious side effects include dyspnea and cardiac arrest, which may cause syncope but typically resolve after discontinuation.

Clopidogrel can be administered with a loading dose of 300-600 mg, followed by a maintenance dose of 75 mg daily.

For UA/NSTEMI patients, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor antagonist is recommended, regardless of whether the patient undergoes medical therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The duration of DAPT is generally at least 12 months. In patients with high hemorrhage risk, de-escalation strategies may be considered, such as switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel or shortening the DAPT duration to 3-6 months.

Activated platelets bind fibrinogen via GP IIb/IIIa receptors, forming platelet thrombi. This is the final and only pathway for platelet aggregation. Abciximab, a monoclonal antibody that directly inhibits GP IIb/IIIa receptors, effectively binds to platelet surface receptors. In clinical practice, tirofiban is more commonly used due to its better safety profile. GPIs are recommended during PCI procedures or for patients undergoing conservative treatment but are not routinely recommended for pre-procedural use.

Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitors mainly include cilostazol and dipyridamole.

Anticoagulation Therapy

Unless contraindicated, all patients should routinely receive parenteral anticoagulation therapy in addition to antiplatelet therapy. The choice of anticoagulant depends on the treatment strategy and the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

For patients undergoing conservative management, anticoagulation therapy can be maintained for 5-7 days after symptom onset. For patients who have undergone successful PCI, routine anticoagulation therapy is not required.

The recommended dosage of unfractionated heparin (UFH) is an intravenous bolus of 80-85 IU/kg followed by a continuous infusion at 15-18 IU/(kg·h). The dose is adjusted based on activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), targeting an APTT of 50-70 seconds. Intravenous heparin is typically administered for 2-5 days, after which it can be switched to subcutaneous heparin at a dose of 5,000-7,500 IU twice daily for an additional 1-2 days. Platelet counts should be monitored during heparin use due to the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

Compared to UFH, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has equal or superior efficacy in reducing cardiac events. LMWH exhibits strong anti-Xa and anti-IIa activity and can be dosed based on body weight and renal function. It is administered subcutaneously, does not require laboratory monitoring, and is more convenient to use. Additionally, the risk of HIT is lower with LMWH. Common LMWH agents include enoxaparin, dalteparin, and nadroparin.

Fondaparinux, a selective factor Xa inhibitor, effectively reduces cardiovascular events while significantly lowering hemorrhage risk. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection of 2.5 mg once daily. Fondaparinux is particularly suitable as the first-choice anticoagulant for patients managed conservatively, especially those at increased hemorrhage risk.

A direct thrombin inhibitor derived from hirudin fragments, bivalirudin specifically and directly inhibits factor IIa activity, prolonging activated clotting time and exerting anticoagulant effects. It prevents contact-induced thrombosis, has reversible and short-lived activity, and is associated with a lower incidence of hemorrhagic events.

Bivalirudin is primarily used for anticoagulation during PCI. It is administered as an intravenous bolus of 0.75 mg/kg, followed by a continuous infusion of 1.75 mg/(kg·h) until 3-4 hours after procedure.

Lipid-lowering Therapy

UA/NSTEMI patients are considered very high-risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Regardless of baseline lipid levels, lipid-lowering therapy should be initiated as early as possible (within 24 hours).

The treatment goal is to reduce LDL-C levels to <1.4 mmol/L (55 mg/dL) and achieve a 50% reduction from baseline.

Statins are the first-line treatment, and the maximum tolerated dose is recommended.

If statin monotherapy fails to achieve target levels or is not tolerated, combination therapy with a cholesterol absorption inhibitor (e.g., ezetimibe) or a PCSK9 inhibitor can be considered.

For patients with high baseline LDL-C levels where statin monotherapy is unlikely to achieve the target, combination therapy can be initiated from the start.

Long-term use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNI) reduces the incidence of cardiovascular events.

If there are no contraindications such as hypotension, oral ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNI should be initiated within 24 hours.

Coronary Revascularization

With the rapid advancement of PCI techniques, PCI has become the primary method of revascularization for UA/NSTEMI patients. The choice of invasive treatment strategy depends on the urgency of cardiovascular risk and the severity of associated complications.

Patients meeting any very high-risk criteria are recommended to undergo emergency coronary angiography within 2 hours of symptom onset, followed by revascularization based on angiographic findings.

High-risk patients are recommended to undergo early invasive treatment (coronary angiography within 24 hours of symptom onset). Intermediate-risk patients are recommended to have elective invasive treatment during hospitalization, typically within 72 hours. For patients without the above risk criteria and without recurrent symptoms, non-invasive testing (preferably imaging) should be performed to identify ischemia before deciding on invasive evaluation. Coronary CT angiography (CTA) may also be used to assess coronary lesions. Patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction undergoing PCI may require cardiac assist devices.

The choice of revascularization strategy depends on clinical factors, operator experience, and the anatomical characteristics of coronary lesions.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) provides the greatest benefit for patients with complex coronary lesions where PCI cannot achieve complete revascularization, patients unsuitable for PCI, those with multi-vessel disease and diabetes, or those with mechanical complications.

Prognosis and Secondary Prevention

The acute phase of UA/NSTEMI typically lasts about 2 months, during which the risk of myocardial infarction or death is highest.

Although the in-hospital mortality rate is lower for UA/NSTEMI compared to STEMI, the long-term incidence of cardiovascular events is similar.

After discharge, patients should adhere to long-term secondary prevention therapies, including:

- Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) usually for 12 months

- Statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors/ARBs/ARNI

- Strict control of risk factors, planned rehabilitation, and appropriate physical exercise